Israel is a complex country that defies simplistic analysis, as Ari Shavit astutely observes in My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel, published by Random House. It’s neither the Land of Milk and Honey that blinkered supporters like to think it is nor is it the racist colonial state that enemies imagine it to be.

The truth, as Shavit observes in this bracing, incisive and nuanced book, lies somewhere in the middle.

“On the one hand, Israel is the only nation in the West that is occupying another people,” he writes, referring to the Palestinian Arabs in the West Bank. “On the other hand, Israel is the only nation in the West that is existentially threatened,” he adds, referring to countries like Iran and organizations like Hezbollah that have called for Israel’s destruction.

Shavit, an Israeli journalist on the staff of Haaretz, is critical of leftist and rightist interpretations of Israel. The left focuses on Israel’s occupation but overlooks the intimidation to which it is subjected. The right concentrates on the intimidation and dismisses the occupation. Unless both elements are addressed, he says, “one cannot grasp Israel or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.”

Challenging both right-wing and left-wing dogmas, he argues that there are no “simple answers” or quick-fix solutions.” Shavit, however, supports a two-state solution, the only sensible and realistic one.

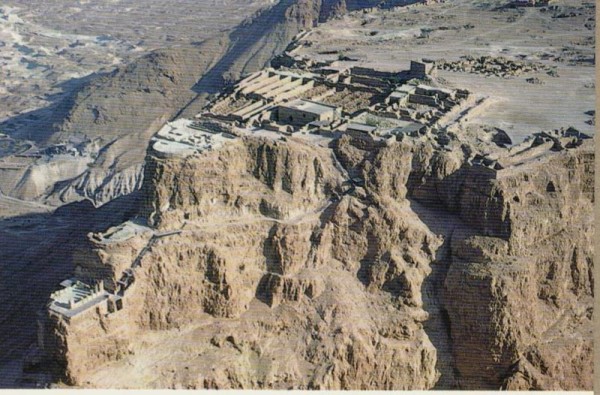

Shavit dwells, as he inevitably must, on the toxic politics of the region. But The Promised Land, one of the finest books of its kind in years, transcends the Arab-Israeli dispute. Calling it “a personal journey through contemporary and historic Israel,” he examines a plethora of topics that help a reader better understand the essence of Israeli society then and now — the orange as a trademark of agriculture, the kibbutz as a pivotal institution and the desert fortress of Masada as a rallying cry of Jewish nationalism.

Shavit’s examination of the Shamouti orange — the large, oval, juicy fruit known today as the Jaffa orange — is instructive. Oranges had always been prized as an export from Palestine. But the modern citrus industry in Palestine/Israel owes its existence to Rehovot, a Zionist settlement near Tel Aviv where “Western know-how, Arab labor and laissez-faire economics merged to make the Jaffa orange a world-renowned brand.”

Shavit discusses two national projects that defined Israel in the early 1950s — the kibbutz, an iconic symbol of Israel, and immigration, a raison d’etre of Zionism.

Kibbutzim, collective settlements, emerged in the first decades of the 20th century, but were given a new lease on life between 1950 and 1951, when more than 100 were built, many on land where Palestinian Arab villages had once stood.

Israel encouraged Jewish immigration, and immigrants arrived in droves, straining the Israeli economy. The 121 primitive encampments that housed a lot of the newcomers were soon phased out and replaced with cheap and functional apartment buildings. “The mass immigration of Jews to the Land of Israel … is Zionism’s greatest triumph,” he says,

For centuries, Jewish historians ignored Masada, where 960 men, women and children took their own lives in 73 A.D. rather than submit to Roman domination. But in the early 1940s, he recounts, Masada was turned into “the new locus of Zionist identity.” And it remains so today.

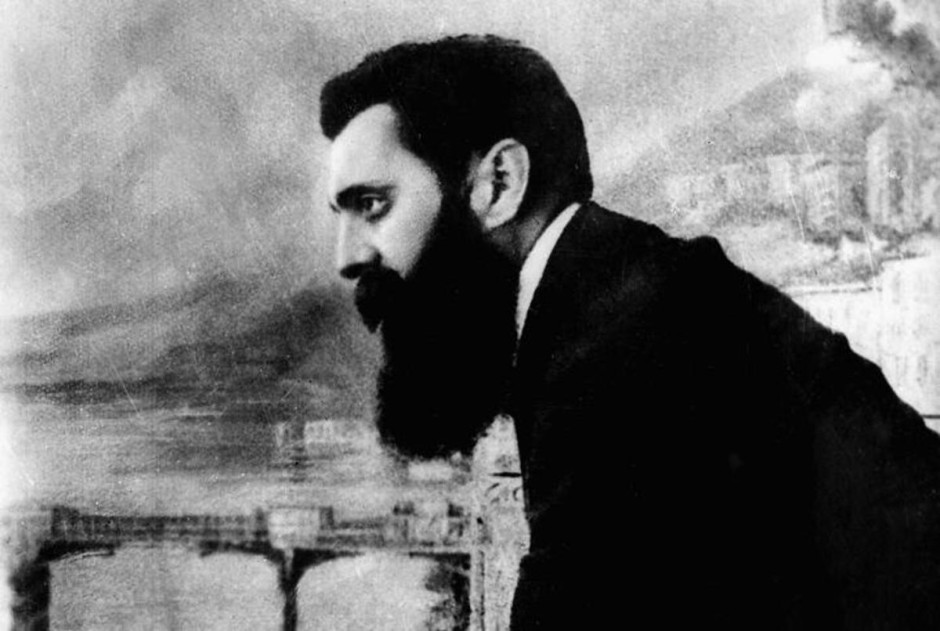

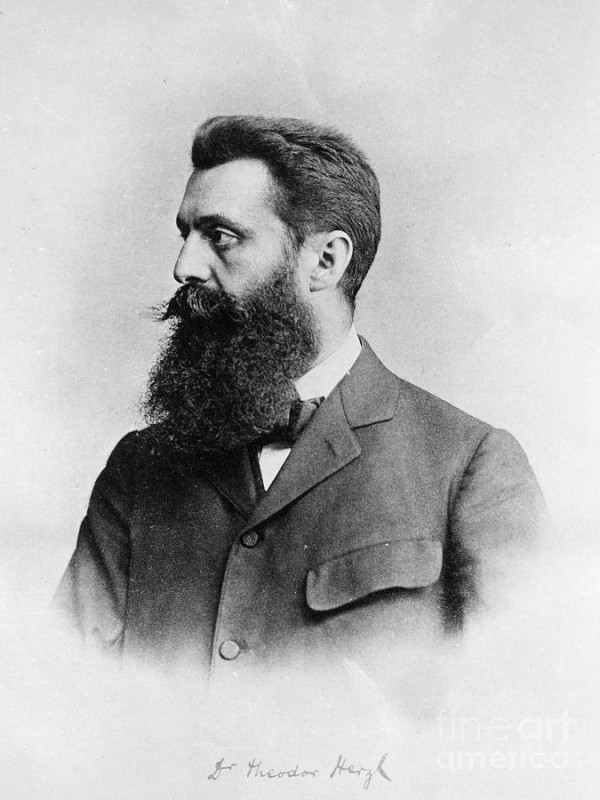

Shavit, whose British great grandfather visited Palestine in 1897, acknowledges that Zionist leaders from Theodor Herzl on down sought imperial backing for a Jewish homeland or state. Their objective, given the oppression of Jews in Europe and elsewhere, was humanitarian rather than colonial.

Of course, the Arab inhabitants of Palestine, comprising a majority of its population, did not see it that way. Nor did they care that Jews had a long and genuine historic, religious and cultural attachment to Palestine. The Arabs took up arms to defeat the newly created Jewish state, and during the first Arab-Israeli war, they suffered the consequences. Tens of thousands of Palestinians left under duress or were forced to flee, never to return to their homes and farms.

In a chapter titled Lydda, 1948, Shavit zeroes in on the expulsion of Palestinians from the town of Lydda — which he describes as “our black box” — and from places such as Safed, Tiberias and the Hula Valley.

The Zionist movement displayed “extraordinary determination, imagination and innovation” to build Israel against all odds. But the miracle of Israel, he admits, is based on denial: “The nation I am born into has erased Palestine from the face of the earth,” he writes, hewing to the narrative that bulldozers razed more than 400 Palestinian villages during and after the 1948 war.

“Denial has its reasons,” he adds. “In the first decade, the unique endeavor of nation building consumes all of the young state’s physical and mental resources. There is no time and no place for guilt or compassion. The number of Jewish refugees that Israel absorbs surpasses the number of Palestinian refugees it expelled.”

Turning to the post-Six Day War era, Shavit focuses his thoughts on the scores of settlements Israel built in the West Bank, a project he correctly brands as “futile, anachronistic and colonialist.” Likening them to Algeria and Rhodesia, Shavit argues that they have “placed Israel’s neck in a noose” and created “an untenable demographic, political, moral and judicial reality.”

According to Shavit, the left is absolutely right about the futility of Israel’s occupation, “a moral, demographic and political disaster.” But he believes the left was somewhat naive about peace. “It counted on a peace partner that was not really there,” he claims without elaboration. “It endorsed the unsound and irrational belief that ending the occupation would bring peace. It overlooked the existence of millions of Palestinian refugees whose main concern was not the occupation but a wish to return to their lost Palestine.”

Israel was right to engage the Palestinians in peace talks, he goes on to say. “But we should never have promised ourselves peace or assumed that peace was around the corner. We should have been sober enough to say that occupation must end, even if the end of occupation did not end the conflict.”

Shavit argues that Israel can only remain a Jewish democratic state if it withdraws from the West Bank. The other options are unpalatable. The occupation will ultimately transform Israel into an apartheid “criminal state” that engages in ethnic cleansing, or into a binational state in which Arabs will eventually become a majority.

As he puts it, “Will the Jewish state dismantle the Jewish settlements, or will the Jewish settlements dismantle the Jewish state?”

Beyond the settlements, Shavit perceives still more threats looming on the horizon.

Israel faces a missile threat from its enemies, a nuclear threat from Iran and a campaign by disaffected Arab citizens for autonomy in the Galilee. And then there is the possibility that secular Jews, the founders of the state, will be outnumbered by ultra-Orthodox Jews one day soon.

Surveying the upsurge of Islamic fundamentalism in the Middle East and the contagion of violence and chaos that have already engulfed neighboring Arab states such as Syria and Iraq, he describes Israel as “a lonely rock in a stormy ocean.” Yet he’s convinced that Israel — a lively and vibrant country — is “more solid than the tempestuous waters surrounding it,” and will meet these challenges with maturity, resolve and strength.