Ariel Sharon, Israel’s prime minister from 2001 to 2006, entered office as a hardliner and left as something of a dove. His astonishing transformation is chronicled in Dror Moreh’s biopic, Sharon, which will be available on the ChaiFlicks streaming service from June 15 onward.

Sharon is one of the films in its new series, The Prime Ministers, which also documents the premierships of David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Rabin.

It is framed by two tragic events — the strokes that incapacitated him in late 2005 and early 2006 and cut short his career. After Sharon slipped into a permanent coma, his deputy, Ehud Olmert, assumed his duties. For the next eight years, Sharon lay in a vegetative state. He died on January 11, 2014, seven years after Sharon was released.

Moreh, a seasoned Israeli filmmaker, covers the highlights of Sharon’s military and political endeavors in this informative film, a blend of file footage and interviews with Sharon and his associates and friends. Moreh glosses over his early years as an Israeli army officer and politician.

Born in Kfar Malal in 1928, Sharon fought in the 1948 War of Independence and in subsequent wars and border skirmishes. One of Israel’s greatest generals and field commanders, he achieved near legendary status during the 1973 Yom Kippur War in the Sinai Peninsula when he broke through Egyptian lines and established a beachhead in “Africa,” or western Egypt.

Having retired from the armed forces following hostilities, Sharon formed a right-wing political party, which he subsequently merged with the Likud, led by Menachem Begin. Moreh takes up the thread of the story at this point, referring to Sharon’s appointment as minister of defence in 1981.

Sharon assured Begin that Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 would last 48 hours and would extend no deeper than 40 kilometres into Lebanese territory. In fact, the conflict degenerated into a 20-year campaign, during which Israel occupied Beirut and attempted to strike a decisive blow against the PLO.

At Sharon’s command, Israel allowed its Lebanese Christian ally, the Phalange, to massacre some 800 Palestinian civilians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. The slaughter greatly tarnished Israel’s image and compelled Sharon to resign, but after a cooling-off period, he roared back as a high-profile minister in various portfolios.

In a reckless act of theater designed to enhance his chances of winning the Likud leadership, Sharon visited the Temple Mount complex in eastern Jerusalem in September 2000. He was accompanied by a multitude of police officers. Their presence triggered Palestinian riots and a strong Israeli police reaction, which, in turn, set off the second Palestinian uprising.

Much to the surprise of observers, Sharon defeated Ehud Barak, the prime minister, in the 2001 general election. In his first official visit to the United States, Sharon presented peace proposals to U.S. President George W. Bush, thereby altering his reputation as a dyed-in-the-wool hawk.

Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security advisor and then his secretary of state, was impressed by his openness to peace with the Palestinians.

Chronologically speaking, Sharon started out as a security hawk. His argument was that Israel should capitalize on its Six Day War victory by building a maze of settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and by widening the corridor to Jerusalem. He was a great believer in the old Israeli adage of creating “facts on he ground.” This is precisely what he did as a government minister.

With the outbreak of the second intifada, Sharon focused on responding vigorously to Palestinian suicide bombings. But at a moment when the Israeli public demanded harsh reprisals, he insisted that restraint was an element of power.

In the wake of the Park Hotel bombing in Netanya in 2002, which resulted in the deaths of 30 Israelis, Sharon ordered the reoccupation of the West Bank in Operation Defensive Shield. During the Oslo peace process, Israel had withdrawn from Arab-populated areas of the West Bank, allowing the Palestinian Authority to govern them. But after the Park Hotel atrocity, Israel reoccupied major Palestinian towns like Ramallah, Jenin and Nablus and tried to marginalize the president of the Palestinian Authority, Yasser Arafat.

As the intifada drew to a close, with hundreds of Israelis having been killed by suicide bombers, Sharon decided that Israel’s occupation of Gaza was no longer viable. “We cannot control Gaza forever,” he said in a speech that shocked, disappointed and angered Jewish settlers there and in the West Bank. In Sharon’s view, the occupation did not serve Israel’s interests.

During the unilateral disengagement from Gaza, Israel demolished all its settlements and repatriated its inhabitants, causing an uproar, particularly among settlers. As part of its withdrawal, Israel evacuated four settlements in the West Bank.

By that juncture, Sharon had left the Likud and formed the centrist Kadima Party.

Saeb Erekat, the chief Palestinian negotiator at peace talks with Israel, was certainly surprised by Sharon’s audacity. “This is the father of the settlements destroying his babies,” he says in a clip.

Before he was felled by strokes, Sharon talked about the prospect of a two-state solution. As well, he discussed the possibility of withdrawing from the bulk of the West Bank and retaining only settlement blocs, says his former chief of staff, Dov Weissglass.

According to his personal secretary, Sharon expressed regret that poor health had foiled his withdrawal plan. “You know, this caught me at the wrong time,” he told her.

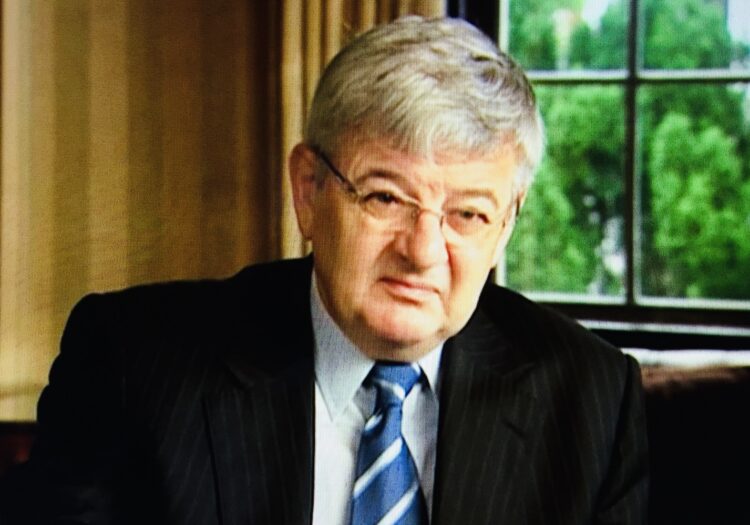

“Sometimes, history is very cruel,” says Joschka Fischer, the former foreign minister of Germany. Fischer knew Sharon and happened to be in Israel during the Dolphinarium suicide attack in June 2001.

Erekat compares Sharon’s fate to a Greek tragedy.

We will never know what might have transpired had Sharon served out his term. But what seems clear is that he rejected the debilitating status quo and tried to reach a pragmatic accommodation with the Palestinians. That may well be one of his legacies.