An exhibition on Auschwitz-Birkenau has landed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto for an extended stay.

Created by Musealia, co-produced by the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in Poland, and developed by an international panel of curators and historians, Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away is one of the most comprehensive exhibitions ever presented on that Nazi extermination camp.

It’s the next best thing next to visiting this former killing center.

Running until September 1, this chilling exhibition contains more than 500 original objects and archival records on loan from the camp and some 20 other major institutions and private collections around the world.

Although it focuses on Auschwitz, the largest Nazi concentration camp, its frame of reference are the cataclysmic events that led to Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, the horrendous persecution of Jews in Germany, and the systemic barbarism of the Holocaust in German-occupied Europe.

The first object that met my eye, inside a glass case, was a woman’s tattered and forlorn red shoe that belonged to an unidentified Jewish deportee. It reminded me of a brief scene in Steven Spielberg’s 1993 epic historical drama, Schindler’s List, during which the camera poignantly panned on a Polish Jewish girl in a red coat during the liquidation of Krakow’s Nazi ghetto. This stark image placed into sharp relief the jarring contrast between innocence and brutality.

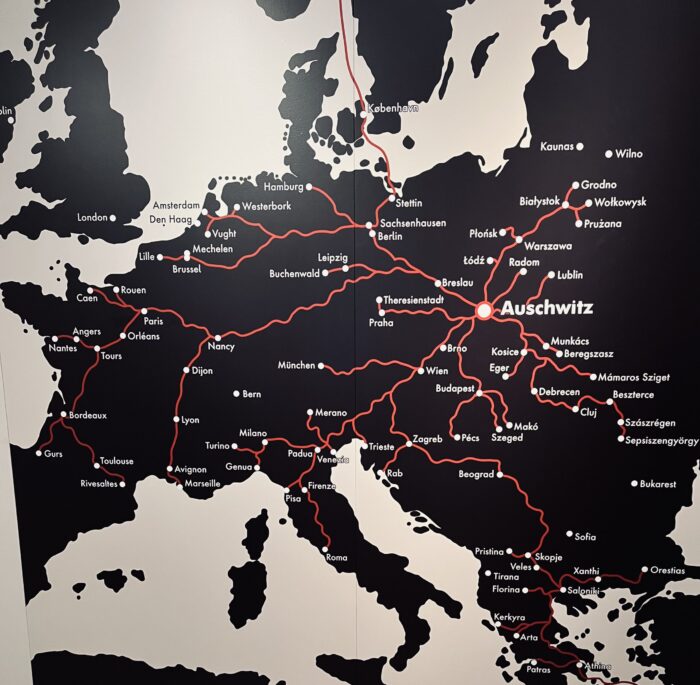

Next to it is a wall mural of a rounded pile of shoes seized from Jewish deportees. Of the 1.3 million people deported to Auschwitz, 1.1 million were murdered. One million were Jews from Poland and across Europe, 72,000 were Polish Christians, 21,000 were Roma and Sinti, 15,000 were Red Army prisoners of war, and 12,000 were Europeans of various origin.

Two photographs of Hitler, at a Nazi rally in 1933 and in Munich in the 1920s, are illustrative of the diabolical fascist who conceived and implemented the Holocaust, which claimed the lives of some six million Jews, or about one-third of the world’s Jewish population.

Oswiecim, the Polish town adjacent to Auschwitz, is featured in a special display. Around half of its population was Jewish on the eve of World War II. Photographs of its murdered Jewish residents, including a man named Solomon Krieser, underscore the tragedy of Polish Jews during the German occupation. In the span of six years, 90 percent of Poland’s Jewish community of 3.3 million was wiped out.

German Jews suffered an almost identical fate, as exemplified by an Iron Cross that was awarded to Salli Joseph for bravery in World War I. Despite his medal, he and his wife, Martha, were killed in a Nazi camp in 1943.

The displays that follow document the rise of Nazism and the upsurge of antisemitism in Germany. A wall mural of a vast Nazi rally in Nuremberg, plus excerpts from Leni Riefenstahl’s classic documentary, Triumph of the Will, are proof that many Germans were seduced by Hitler.

Another display, The Expulsion of Jews, charts the vicious litany of boycotts and race edicts that excluded Jewish Germans from society. The most draconian one, the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, is inscribed in the Reich Legal Gazette, which sits in a glass case. Most Germans reacted to these events with a deafening silence, a label reads.

By 1936, the autocratic Nazi regime had opened a network of concentration camps, such as Dachau and Sachsenhausen, to imprison dissidents and enemies of the state.

European Jews faced tremendous perils during that period, as Chaim Weizmann, the president of the World Zionist Organization, noted: “There are now two sorts of countries in the world, those that want to expel the Jews and those that don’t want to admit them.”

Canada was one of the nations that drastically limited Jewish immigration in the 1930s and 1940s.

Jews trapped in countries ruled by antisemitic regimes desperately tried to leave. Shanghai, a port in China which required no entry visas, was one of their destinations.

In 1939, Hitler addressed the Reichstag in a major speech, hypocritically warning Jews he would hold them responsible for starting the next war. Once it broke out, Germany attempted to solve the Jewish “problem” by concentrating Jews in a reservation near the Polish city of Lublin or by sending them off to the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar.

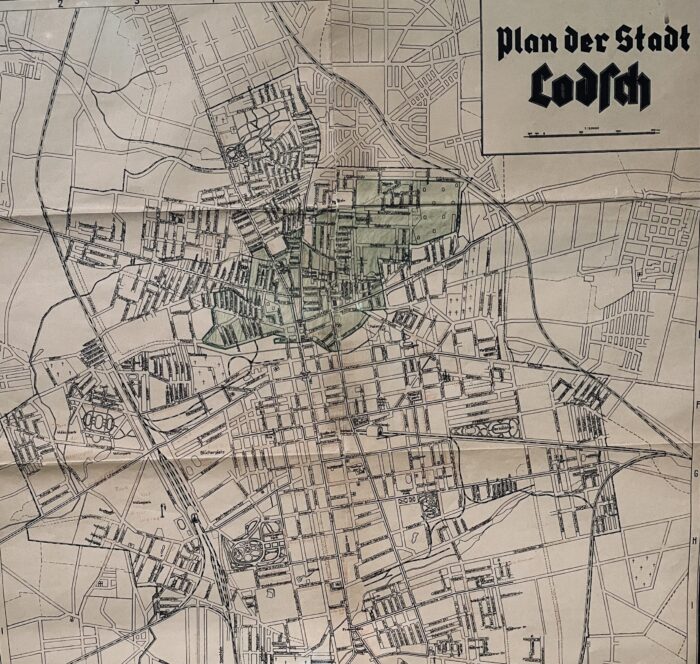

Since neither plan was feasible, the Nazis pushed Jews into sealed ghettos in eastern Europe. A German map of Lodz, a city in central Poland, is shaded in green to denote the location of the ghetto, the last one to be liquidated by the Germans. Lodz’s ghetto currency is displayed, as are German ration cards for milk in Lublin’s ghetto.

A separate section is devoted entirely to Auschwitz, one of six major concentration camps built by the Nazis in Poland to murder Jews. These camps, ranging from Treblinka to Sobibor, consumed the lives of 1.7 million Jews under Operation Reinhard. It was named after Reinhard Heydrich, one of the architects of the Holocaust and the SS chieftain whom Czech partisans assassinated near Prague in 1942.

Auschwitz’ first inmates were Polish political prisoners. Captured Russian soldiers were brought there following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. The first victims herded into the gas chambers were 1,000 Red Army soldiers, who suffocated after inhaling the poisonous gas Zyklon-B.

The four crematoria in Auschwitz could dispose of 4,416 corpses per day.

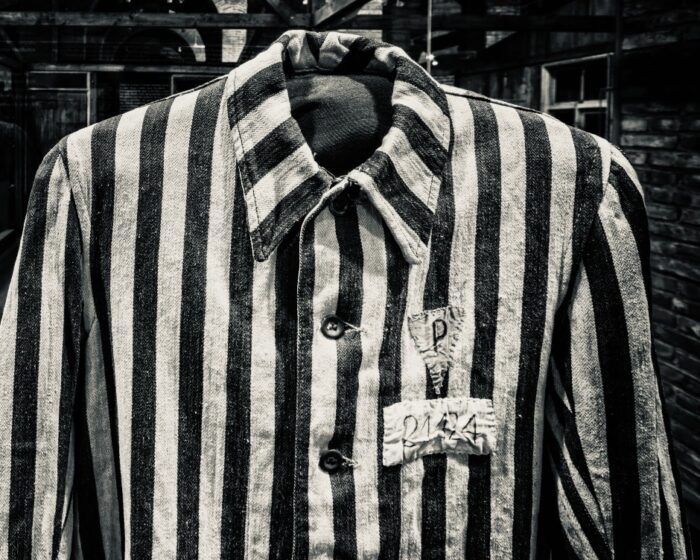

The most striking artifacts here are a weathered wooden whip used by kapos to beat inmates, a striped blue and white uniform worn by prisoners, and a wooden triple bunk bed where they slept.

There are mug shots of inmates. About 50,000 such photographs were taken until the practice was discontinued in 1943. There is a photo gallery of the Germans who administered Auschwitz, as well as an enlarged photograph of workers sorting through a mountain of goods at Kanada. Named after Canada, a land of wealth, it was an enormous warehouse filled to the brim with the worldly possessions of Jews slaughtered in Auschwitz.

The gruesome medical experiments performed by Joseph Mengele on helpless inmates are clinically noted. Two inmates, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Weztler, are memorialized. They escaped from the camp in 1944, relaying their explosive information to the Jewish leadership in Hungary before the Holocaust got under way there.

Auschwitz was liberated by the Red Army on January 27, 1945, but before Soviet troops reached the camp its remaining Jewish prisoners were sent on a death march that killed thousands of them.

Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away is an impressive exhibition, combining the rigors of scholarship with the emotions of a mass atrocity. It leaves a visitor shaken in the knowledge that an advanced European country was capable not only of profound cruelty but of genocide on a massive scale.