Latvia and Lithuania, which are among the newest members of NATO, have been hailed by some as Western bastions of democracy and bulwarks against Russian expansionism. But both Baltic republics were complicit in the mass murder of their Jewish citizens during the Holocaust.

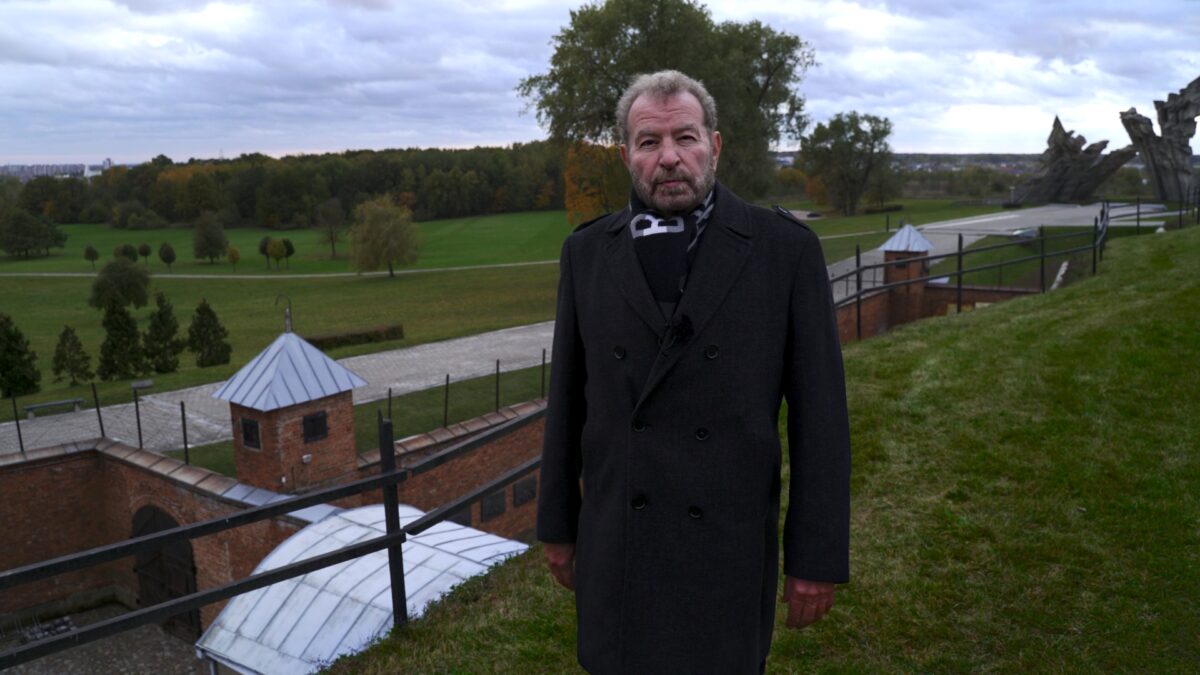

Baltic Truth, a revealing and troubling documentary by Eugene Levin and Andrejs Hramcovs, explores this dark dimension of their history. Hosted and narrated by the Israeli cantor and singer Dudu Fisher, it has been acquired by Menemsha Films.

Fisher, whose ancestors were Latvian Jews, takes viewers on a tour of killing sites in both countries during which Holocaust survivors and witnesses are interviewed.

In nearly every instance, the perpetrators of these crimes were Latvian and Lithuanian fascists rather than German occupying forces, as he correctly notes. Yet today, these murderers are hailed as nationalist heroes because of their tole in resisting communism during the 1940 Soviet occupation and the postwar period, when Latvia and Lithuania were annexed and incorporated into the Soviet Union.

With the implosion of the Soviet Union, both nations declared independence and aligned themselves with the West, which plays down or ignores their complicity in the Holocaust. Critics who bring up this sensitive subject are swiftly met with the standard and hackneyed rebuttal that Russia is trying to undermine their sovereignty.

The vast majority of Latvian and Lithuanian Jews were murdered in the summer and autumn of 1941, following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Fisher guides us through this gruesome process as he travels from one place to another.

He starts in Riga, the Latvian capital, where 100,000 Jews, including 30,000 German and Austrian Jews, were herded into a ghetto. At the nearby Rumbula forest, they were shot in mass executions.

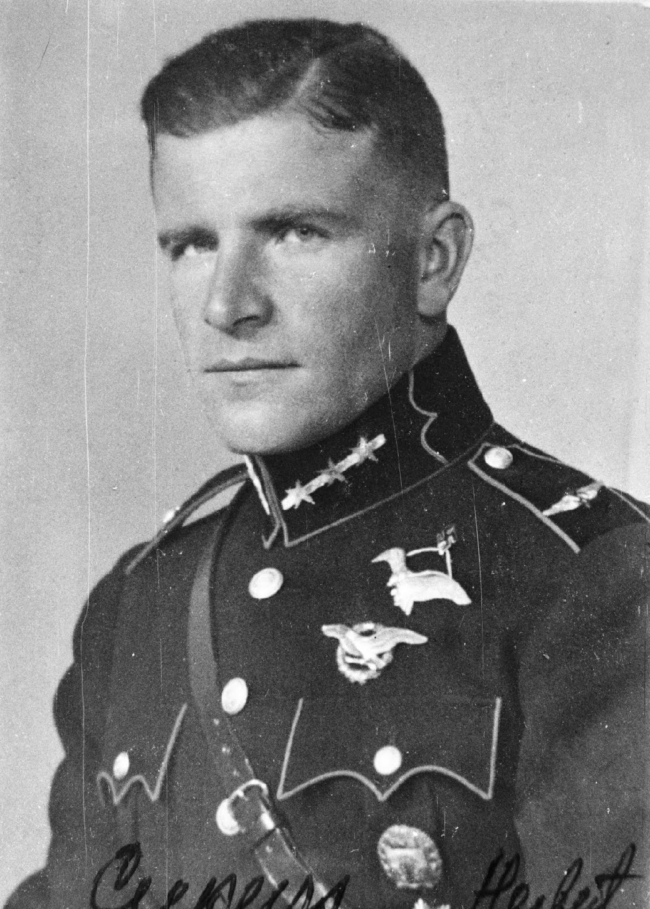

Herberts Cukurs, a Latvian national hero who would be known as the Butcher of Riga, participated in these atrocities. He was assassinated by the Mossad in Montevideo in the mid-1960s.

Voldemars Veiss, a high-ranking Latvian police officer, rounded up Jews in Riga. He is buried in a Riga cemetery reserved for Latvian heroes.

In the town of Akniste, 175 Jews were slaughtered in a pogrom on July 18, 1941. The killers were Latvians, some of whom knew the victims as neighbors. One of the perpetrators, Vilis Tunkelis, is considered an anti-communist hero and is buried in a local cemetery.

Seventy thousand Lithuanian Jews from Vilnius (Vilna) were executed by Lithuanians in the Ponary forest.

Jonas Noreika, a Lithuanian who was involved in a pogrom in the town of Siauliai in August 1941, was exposed as a criminal by his granddaughter, Silvia Foti, in a best-selling book.

The Jews of Kaunas (Kovno) were murdered in the Ninth Fort, a facility built by czarist Russia to protect the city from German incursions.

As Fisher points out, the Lithuanian author Ruta Vanagaite was hounded out of the country after her book on the Holocaust was published.

Ten thousand Jews in Ukmerge were killed during this era, but today a monument in this town pays homage to Juozas Krikstaponis, one of its former residents. He murdered a relative of Shimon Peres, Israel’s former prime minister and president, and participated in the killing of Jews in Belarus.

Efraim Zuroff, the head of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Jerusalem, laments that Latvians tend to focus on fellow citizens who suffered under communism while ignoring the Jewish victims of the Holocaust.

His critique is offset by Fisher, who claims that Lithuanians and Latvians who opposed the persecution and extermination of Jews were unable to help them. Nonetheless, 873 Lithuanians and 423 Latvians came to their rescue, and they were honored by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, as Righteous Gentiles.