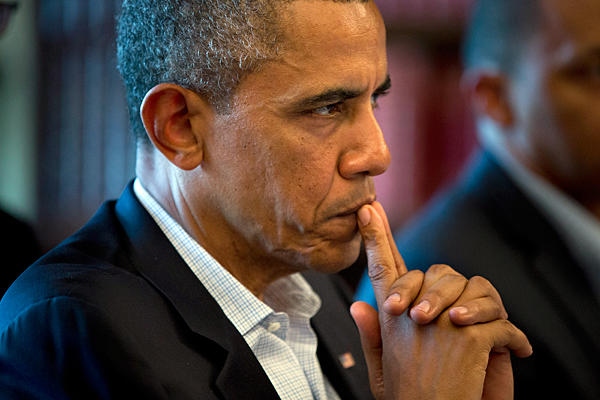

The Middle East has kept Barack Obama extremely busy, if not preoccupied, since he assumed office in 2009.

Obama has had to grapple with a multitude of challenges in this turbulent region, from Israel’s perennial struggle with the Palestinians and Iran’s quest for an atomic bomb to the revolutionary Arab Spring rebellions that have toppled dictators and the civil wars in Libya and Syria that have altered the political landscape.

On top of it all, he has been faced with the task of withdrawing U.S. troops from Iraq and considering a pull out of American forces from Afghanistan.

More recently, Syria’s chemical weapons stockpile and Iran’s nuclear program have been the issues that have drawn Obama into the whirlpool of Middle Eastern politics.

As a result, Obama has spent more time on the Mideast than any other foreign policy issue.

But has he managed to come to grips with these thorny problems successfully? If you ask Fawaz Gerges, a professor of Middle Eastern politics at the London School of Economics and the author of Obama and the Middle East, published by Palgrave Macmillan, the answer is not necessarily.

In this sweeping and contemplative work, Gerges examines not only Obama’s record, but places it within the context of American Mideast policy, which hinges on preserving U.S. access to Arab oil reserves, ensuring Israel’s security and maintaining friendship with traditional allies like Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf sheikdoms.

Obama’s predecessor, George W. Bush, proceeded from the premise that the best way to protect U.S. interests in the Mideast was through the promotion of democracy, even by preemptive means. “Stability cannot be purchased at the expense of liberty,” he said in 2003. But after Hamas won the election in the Palestinian territories in 2006, Bush’s enthusiasm for democracy waned.

Distancing himself from Bush’s legacy, Obama announced his policy would focus on the attainment of stability, reject the principle of the liberal and unilateral deployment of force in international affairs, and promote outreach to American foes such as Iran.

“In this, Obama came closer to the dominant realist approach of American foreign policy toward the region that aimed at retaining the status quo through backing pro-Western Arab rulers and eschewing moral imperatives,” Gerges writes.

From a historic perspective, the United States was a minor player in Mideast affairs until the end of World War II. Not having been a colonial power there, like Britain and France, the United States generally projected a positive image. But America’s position deteriorated after it recognized Israel, supported a coup against a popularly elected prime minister in Iran, upgraded support for Israel in the wake of the Six Day War and invaded Iraq, he observes.

Gerges is of the view that the unresolved Palestinian problem, coupled with Washington’s unstinting support of Israel, has caused more damage to the United States’ standing in the Mideast than any other issue. Elaborating on this point, he argues that the Arab-Israeli peace process has exposed the gap between rhetoric and action in the Obama administration.

Obama raised expectations about the need for a two-state solution, but failed to convince Israel that a settlement freeze in the West Bank would serve the interests of peace. Nevertheless, Israel and the Palestinian Authority are currently engaged in peace talks under the auspices of the United States.

Gerges also underscores the glaring disconnect between Obama’s criticism of Israel’s settlement construction and his decision to vote against granting the Palestinian Authority non-member observer status at the United Nations.

In his opinion, America’s “dysfunctional political culture,” in which special interests play a special role, has imposed “severe constraints” on Obama’s ability to pursue an even-handed policy toward “the Palestine question.”

Gerges suggests that the United States should engage Hamas because it has supposedly evolved and signalled a readiness to recognize Israel. But where is the evidence for this unsubstantiated assertion? Hamas spokesmen tirelessly reiterate that Hamas will never recognize Israel and will only consider a long-term truce with the Jewish state if certain conditions are met.

In appraising Obama’s Mideast policy, Gerges perceives “more continuity with the past than real change.” As he puts it, “His administration aims at retaining the status quo with a few minor corrections.”

Obama has reached out to the Muslim world, promised to reduce the U.S. military footprint in the Mideast and worked for the creation of a Palestinian state. But according to Gerges, he has singularly failed to “translate his hopes and promises into concrete policy.”

With Iraq and Afghanistan in mind, Gerges praises Obama for having recognized the limits of U.S. power in the Mideast.

He claims that Obama’s “greatest political achievement” lies in having nourished an exceptionally close strategic relationship with Turkey, while his “greatest gamble” is predicated on working out a viable arrangement with Iran. Obama’s post-election promise of engagement with Iran was replaced by confrontation, but now that Iran has a new president in the person of Hassan Rouhani, a supposed pragmatist, Obama may yet be able to forge some kind of a rapprochement with the Iranian government, provided it agrees to significantly scale back its nuclear ambitions.

Citing “illegal and unjust wars” in Iraq and Afghanistan that have undermined the “moral foundations of American power and authority,” Gerges claims that “we are witnessing the beginning of the end of America’s moment in the Middle East.”

This is probably a hasty, half-baked conclusion, judging by events that have transpired since Gerges finished this book. Obama’s handling of the recent Syrian crisis was clearly a sign of irresolution and weakness, but the United States remains the key player in the Middle East, notwithstanding Russian attempts to regain its former preeminent status in the region.