David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, looks back at his life and reflects on Israel’s situation in Yariv Mozer’s informative documentary, Ben-Gurion, Epilogue, which will be presented online by the ChaiFlicks streaming service during its Israel Independence Day Film Festival from May 4-9.

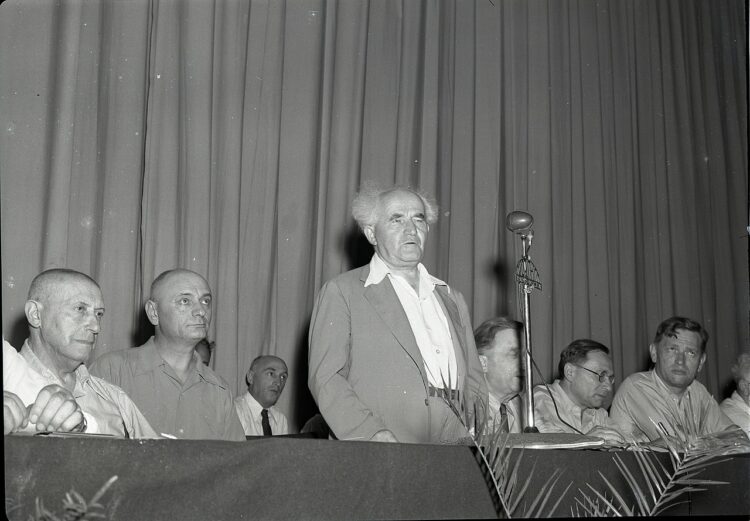

A pivotal figure in the Labor Zionist movement and a founding father of Israeli statehood, he was chairman of the Jewish Agency and the prime minister and defence minister from 1948 to 1954. He held these positions again from 1955 to 1963. He remained in the Knesset until 1970, when he retired from politics.

A substantial segment of Mozer’s movie, filmed in 1968 by a British crew, is set in Sde Boker, a spartan kibbutz in the Negev desert where Ben-Gurion and his wife, Paula, lived for many years. Ben-Gurion was not fond of cities, believing that Israel’s future development lay in settling the Negev, which comprises two-thirds of its land area.

The film is composed as well of clips from interviews conducted by British and American interviewers over the years.

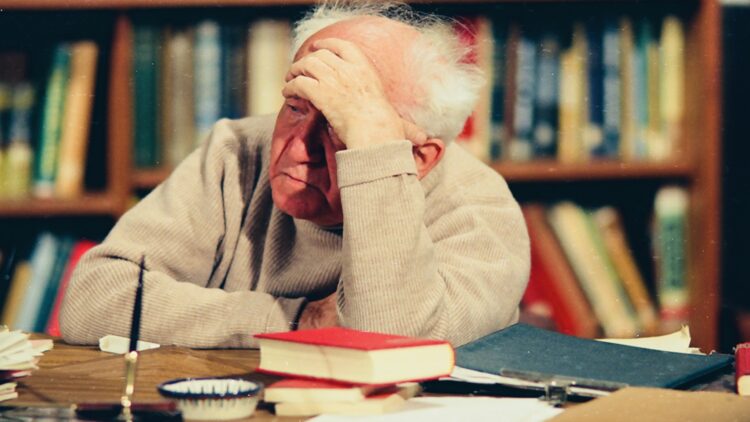

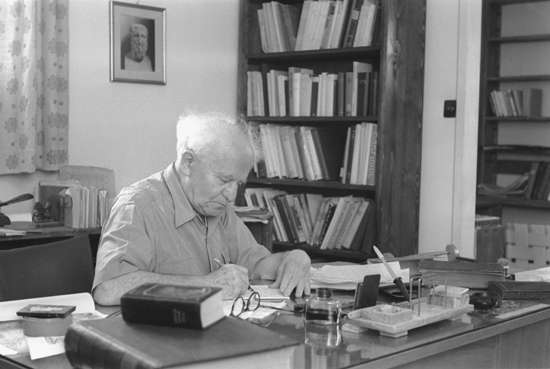

Ben-Gurion was 82 and apparently in good health when he was interviewed by Clinton Bailey, a resident of Sde Boker and an American scholar who had made aliyah. Ben-Gurion was then writing a book about the history of Israel, a project he never completed. He died five years later, several months after the Yom Kippur War.

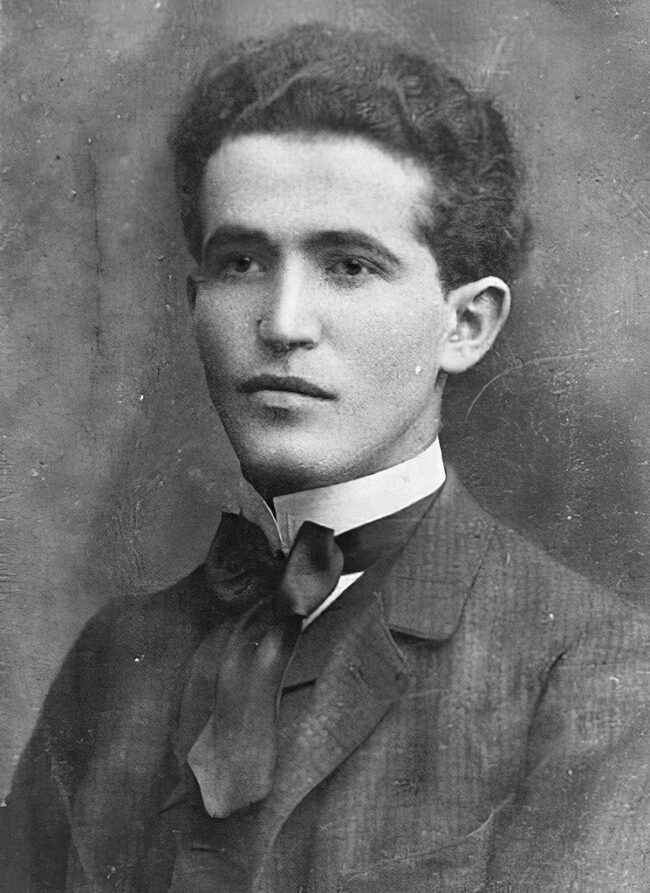

Born in the Polish town of Plonsk, he arrived in Ottoman Palestine in 1906, disembarking at the port of Jaffa. It was his intention to be a farmer, but circumstances drove him in a different direction. After he contracted malaria, his father, who had financed his voyage to Palestine, urged him to return home Claiming he was “reborn” in Palestine, Ben-Gurion was determined to stick it out, unlike many European immigrants who could not tolerate the hardships and left after a year or less.

Proceeding from the assumption that Jews had a right to this land, though they were vastly outnumbered by Muslim and Christian Palestinian Arabs, he contends that Jews were “reclaiming” what was theirs. The early Jewish pioneers, he adds, came in peace.

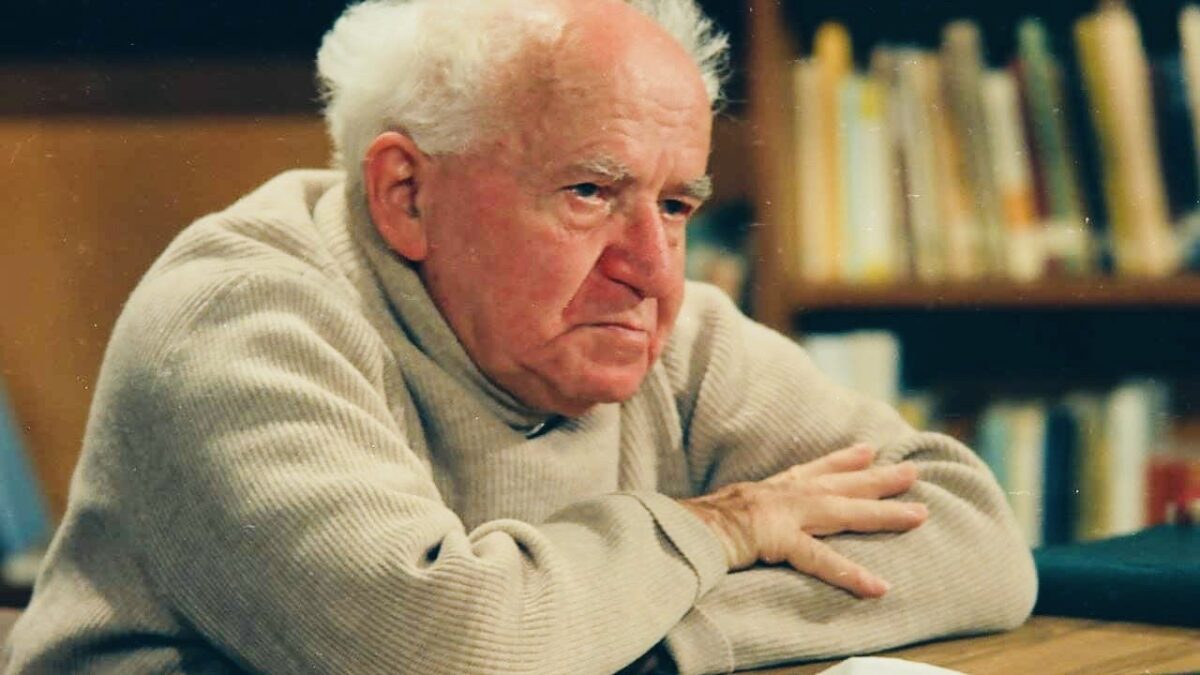

Ben-Gurion, clad in a bulky beige sweater and loose pants of the same color, speaks fluent English with a Yiddish inflection. He strikes a viewer as an unpretentious, down-to-earth, practical person with a cut-and-dried demeanor who speaks to the point and rarely rambles. Bailey is a scatter-shot interviewer. He hardly asks supplementary questions, and often segues abruptly into unrelated topics.

Asked about his controversial decision to accept reparations from West Germany, Ben-Gurion dismisses as “unjust” the notion that all Germans were Nazis. He emphatically says that West Germany’s first chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, whom he met in 1960 in New York City, was not a Nazi. He also believes that the West German state cannot be compared to Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

Ben-Gurion lauds Winston Churchill, Britain’s wartime prime minister, as “a good friend of Zionism,” but acknowledges that the Allies were remiss in not bombing the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland.

In a clip, Ben-Gurion is seen working assiduously on Sde Boker like any other kibbutznik. He was not an elitist, considering himself a man of the people.

“I can exist without politics,” he claims. But his wife, sitting nearby, disagrees. “No, he can’t,” she chimes in.

He describes her as a “remarkable woman,” but defines her as an “American” rather than as a “Zionist.” She thought he was “mad” when he decided to move to Sde Boker following his first resignation.

Ben-Gurion was confident that Israel could win the 1948 War of Independence, provided it could acquire sufficient weapons.

In the wake of the Six Day War, he was asked whether he would prefer peace with the Arabs rather than retaining Israel’s fresh territorial conquests. “We are entitled to all of Israel,” he says. “It’s our country.” But he advises Israel to withdraw from the West Bank and the Sinai Peninsula, keeping only East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights.

He thinks that Israel will have to fight another war to fend off its enemies. He regrets that Israel has had to sacrifice its youth and “best brains” to maintain its security.

On his 85th birthday, in 1971, Ben-Gurion delivered a speech in the Knesset, saying that while Israel was not yet an “exemplary nation,” it had the potential to be one.

In a related clip, the American jazz musician Ray Charles plays the piano and belts out a song. As Ben-Gurion listens intently, Charles lingers on a line that must surely have appealed to him: “Heaven help the people with their backs against the wall.”

Bailey, in closing, asks what he has achieved.

Rather than dwelling on his accomplishments as a nation builder, he speaks in very general terms. “A single person cannot change things,” he says. “It has to be done by the people.”

Deflecting Bailey’s question, he insists he did not “guide” Israel to statehood. “I guided myself.”

And with that observation, Ben-Gurion leaves the room and walks toward his simple hut, accompanied by an armed soldier and a few bodyguards.

For further information about the festival, click on www.JewishFilmFests.com.