During 16 days in the summer of 1936, all eyes were on Berlin as Nazi Germany hosted the eleventh Olympic Games. Oliver Hilmes’ vivid book, Berlin 1936: Sixteen Days in August (The Bodley Head), published originally in German, recreates this event through a cast of carefully chosen characters and against the backdrop of ominous developments.

As Hilmes points out, Adolf Hitler’s popularity reached an all-time high as athletes from around the world assembled in Berlin. Even anti-Nazi members of the working-class were in awe of the German chancellor, who had been appointed to his position three years earlier. “Why can’t we admit that even people who used to vote left are impressed?” noted Willy Brandt, a German leftist in exile who would be chancellor of West Germany in the 1970s.

Five months before the Games were officially opened, the German army reoccupied the demilitarized Rhineland, which had been wrested from Germany following its defeat in World War I. Hitler described this violation of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles as “a restoration” of Germany’s “national honor and sovereignty.”

In the summer of that year, the German government began building Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp only eight kilometres from the outer limits of Berlin.

On the eve of the Games, the Nazis toned down their antisemitic campaign, temporarily suspending the publication of Der Sturmer, a rabidly antisemitic newspaper edited by Julius Streicher. By then, Germany was planning to unveil the Nuremberg laws, which would strip German Jews of their citizenship and forbide marriages between Christians and Jews.

Two weeks before the opening of the Games, Sinti and Roma dwellers of Berlin were removed from their homes and concentrated in an encampment on the outskirts of the city.

One of the driving forces behind the Games, Theodor Lewald, was the 75-year-old president of the German Olympic Organizing Committee. Because he was half-Jewish and thus racially “impure,” he knew his days as a ranking German official were numbered.

As the Games got under way, Poland’s ambassador to Germany, Jozef Lipski, tapped a French friend on the shoulder and said, “We have to be on our guard against a people with such a talent for organization. They could mobilize their enquire nation just as smoothly for war.”

Little did he know that Germany would invade Poland just three years later, touching off World War II.

Ottilie Tilly Fleischer, a 24-year-old javelin thrower from Frankfurt am Main, won the first gold medal for Germany. Her triumph was recorded by Leni Riefenstahl, who made a stylish documentary about the Games for Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels.

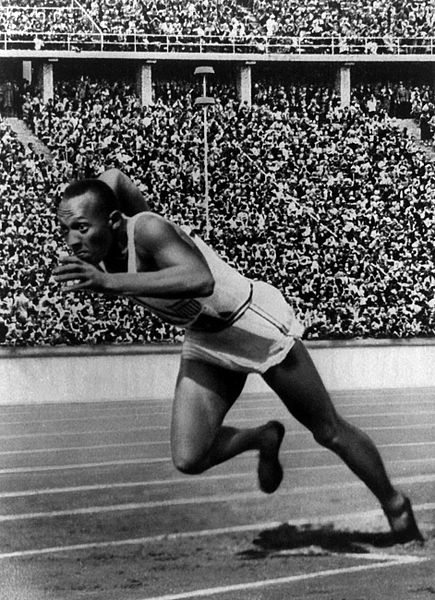

Hitler and his entourage were disappointed by the results of the track and field events. Jesse Owens, the great African American sprinter, won the gold medal in the 100 meters race. The German competitor finished in fifth place. When it was suggested to Hitler that he have his picture taken with Owens, he snarled. “The Americans should be ashamed of letting Negroes win their medals,” he said. “I’m not shaking hands with this Negro.”

Being a racist to the core, Hitler had an explanation for Owens’ victory: “People whose forefathers came from the jungle are primitive — more athletically built than civilized white people.” Hitler added that blacks should be excluded from future Games.

Hitler’s notion of white superiority took another knock when Owens defeated the German athlete Carl Ludwig (Lutz) Long in the long jump. Owens and Long left the field arm in arm in a gesture of camaraderie that infuriated the Nazis.

Bending to pressure, Germany was forced to include the half-Jewish fencer Helene Mayer on its Olympic squad. Mayer, who had won a gold medal in the 1928 Games in Amsterdam, won the silver medal in Berlin. At the awards ceremony, she thrust out her arm in the Hitler salute, dumbfounding Jews and opponents of the Nazi regime.

The coach of the U.S. track team, Lawson Robertson, caused a furore when he benched Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller — two Jewish sprinters who were supposed to run in the 400 meter relay — and replaced them with Owens and Ralph Metcalfe. Glickman and Stoller claimed they had been the victims of antisemitism. “It’s understandable that the disappointed athletes might think this,” says Hilmes, “but in reality the logic behind the coach’s decision (was) simple.” Robertson believed his team would be unable to win the gold medal unless the strongest sprinters, Owens and Metcalfe, were chosen.

Although the German government shelved its antisemitic campaign during the Games, the atmosphere remained fraught for some. Wolfgang Furstner, a captain in the Wehrmacht, was in charge of the Olympic Village until a higher ranking officer took over in the spring of 1936. From that point forward, he was the unofficial mayor of the village, but was compelled to relinquish his position after it was discovered his paternal grandfather was Jewish.

A similar fate awaited Leon Henri Dajou, the proprietor of the Quartier Latin, one of the most fashionable nightclubs in Berlin. Dajou, a Romanian Jew whose real name was Leib Moritz Kohn, had played host to Nazi officials and had even donated money to the Nazi Party. But after his cover was blown, he fled Germany. All this took place as the Games unfolded.

The 1936 Games were a public relations coup for the Nazi regime, but behind the facade everything remained exactly the same. Once the foreign athletes left Germany, the regime’s true colors manifested themselves in all their ugliness and brutality.