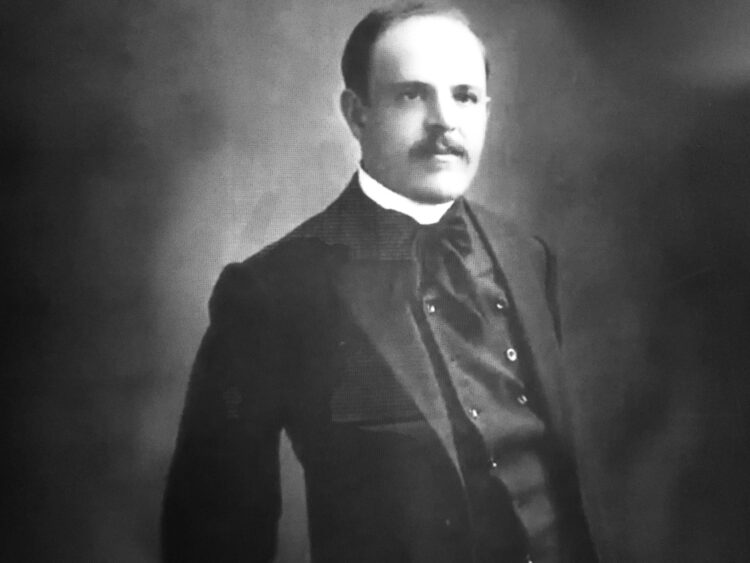

Chaim Nachman Bialik is Israel’s national poet, though he was not born in what is now Israel and lived there for only about a decade.

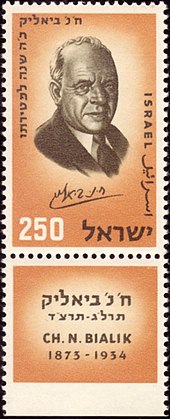

A Russian Jew and a fervent Zionist, he played a central role in the revival of the Hebrew language and culture. A street was named after him in Tel Aviv, and a postage stamp was issued in his honor in 1959, 25 years after his untimely death.

Yair Qedar’s documentary, Bialik: King of the Jews, is currently being screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation. A melange of archival footage, old photographs, animation, commentaries by Israeli scholars and readings of his poems, it’s an evocative film of a poet who broke through the limits of imagination and won the hearts and minds of Hebrew speakers from Poland to Palestine.

Mired in poverty after his father’s death, he was raised by his grandfather. As a young man, he settled in the Ukrainian port city of Odessa, where his first volume of poetry was published when he was 28.

Bialik was profoundly influenced by the 1903 pogrom in Kishinev, the first to be photographed. Visiting Kishinev shortly after the violence had abated, he was inspired to write one of his most moving poems, The City of Slaughter. No pacifist, he urged Jews to strike back and wreak vengeance on the antisemitic perpetrators.

Paying his first visit to Palestine in 1909, when it was a neglected and backward province of the Ottoman Empire, he was greeted effusively by Jews. Yet Bialik was not impressed by the sights. Palestine seemed “antiquated” and did not “pull at his heart.” Bialik was not a “gushing” Zionist, says one of the scholars who offers an appraisal of him.

In passing, Qedar touches on his relationship with the artist Ira Jan, who illustrated one of his books of poetry. Although Bialik was a married man, he appears to have been romantically involved with Jan.

The new Bolshevik regime in Russia arrested Bialik in 1921 and briefly detained him. To the Bolsheviks, Hebrew was a bourgeois and counter-revolutionary language. Left with no alternative but to leave, Bialik immigrated to Palestine. He was 51.

He loved Tel Aviv, which reminded him of Odessa. “Tel Aviv grows by the hour,” he wrote.

Revered as an icon of Hebrew culture by the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Mandate Palestine, Bialik soon grew weary of the public adoration. He departed on a tour of Eastern Europe, spending a considerable bulk of time in Poland. Bialik, though a dyed-in-the-wool Zionist, was deeply attached to the Diaspora.

Succumbing to a fatal heart attack in Vienna, he was buried in Palestine. Tens of thousands of Jews attended his funeral, saddened by the passing of an immortal.

Nearly a century later, Bialik is a treasured figure in Zionist mythology. Bialik: King of the Jews places him in that category.