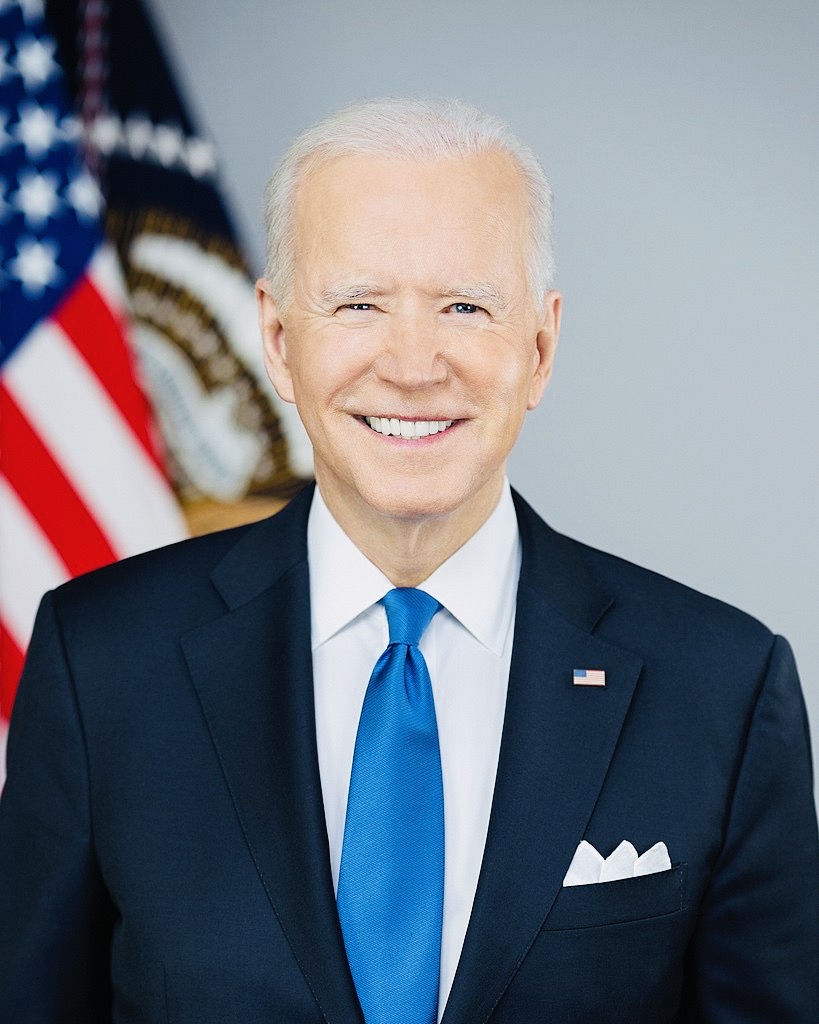

U.S. President Joe Biden will confront a daunting array of issues during his whirlwind visit to the Middle East from July 13-16.

Biden will spend the first leg of his trip in Israel. There he will meet the caretaker prime minister, Yair Lapid, and his predecessor, Naftali Bennett, who met Biden at the White House last August. Biden will also talk to Defence Minister Benny Gantz, and opposition leader and former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who hopes to return to power after the next election in November.

In addition, Biden will confer with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah.

After two days in Israel, Biden will fly to Jeddah, in the first direct flight from Ben-Gurion Airport to Saudi Arabia. There he will hold discussions with King Salman and his son, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and appear at an Arab summit attended by Gulf Cooperation Council countries — Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates — and Egypt, Jordan and Iraq.

Biden’s trip signifies that the United States intends to maintain, if not reinforce, its paramount position in the Middle East as Israel’s chief ally and to strengthen its cooperation with Arab allies such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt in the face of Iran’s destabilizing regional ambitions.

Biden seeks to convey the unmistakable message that the United States will deepen its national security interests in the area despite the current war in Ukraine, the geopolitical and economic challenges posed by authoritarian regimes in Russia and China, the lingering coronavirus pandemic, and the soaring rate of inflation in the West.

In short, Biden wants to assure Israel and Arab friends that they can count on him, and that the United States has no intention of disengaging from the Mideast.

Israel’s leadership regards Biden’s visit as a vital opportunity to achieve two strategic objectives: to reaffirm the “unbreakable” bond between Israel and the United States, and to devise a joint plan of action to slow down, if not stop, Iran’s budding nuclear program.

It was kept in check until Donald Trump, the former U.S. president, unilaterally pulled out of the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement in 2018. Since then, Iran has begun enriching uranium to unacceptable levels, alarming Israel and prompting the Mossad to accelerate its covert sabotage operations against Iranian nuclear facilities and personnel.

Israel opposes a return to the old accord, but would consider endorsing a stronger and longer agreement that effectively prevents Iran from progressing toward a nuclear capability, that curbs its ballistic missile program, and that dismantles its anti-Israel alliances with Syria, Hezbollah, Hamas and the Houthis in Yemen.

Since last April, the signatories of the agreement — Iran, the United States, Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany — have been trying to resurrect it in negotiations in Vienna, but they have borne no fruit so far.

In the meantime, the United States has been building a regional air defence system to counter Iran’s arsenal of missiles and drones. Israel and conservative Arab states such the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, which normalized relations with Israel under the 2020 Abraham accords, are in the forefront of this project.

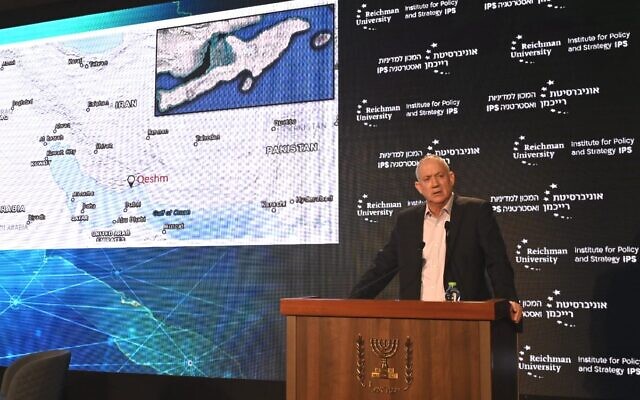

“We are building a partnership with (Arab countries) to ensure a secure, stable and prosperous Middle East,” said Gantz recently.

Israel’s bilateral relations with these Arab states have grown tremendously since the Abraham accords and the decision by the United States in 2021 to shift Israel from U.S. European Command to the Central Command (CENTCOM), which is in charge of American operations in the Arab world.

Saudi Arabia, the seat of Islam and a major oil producer, has a cooperative relationship with CENTCOM, but in the absence of a resolution of Israel’s protracted conflict with the Palestinians, the Saudis are reluctant to recognize Israel and engage in normalization. By all accounts, King Salman is a vehement opponent of normalization, but the crown prince supposedly favors it.

Until a few weeks ago, speculation abounded that Saudi Arabia would cozy up to Israel. John Kirby, the spokesman of the U.S. National Security Council, told a press conference that one of Biden’s objectives would be to encourage Arab states which still have no formal relations with Israel to form ties with it.

This will not materialize any time soon.

“We are not going to be announcing a normalization with Saudi Arabia on this trip,” Thomas Nides, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, said in a candid admission a few days ago.

Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security advisor, said on July 11, “Normalization of any kind would be a long process.”

On the same day, Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Idan Roll underscored this point. “Any possible steps with Saudi Arabia will be probably different than what we’ve seen with the Abraham accords,” he said. “I don’t think we’re going to wake up and find out we have a signed agreement with Saudi.”

In his view, Israeli-Saudi normalization will most probably occur in stages, though Roll expressed the hope that Biden may well nudge the Saudis incrementally toward this goal.

No important policy announcements are expected to emerge from Biden’s meeting with Abbas, but Biden will most likely restate his commitment to a two-state solution, which the current Israeli government opposes.

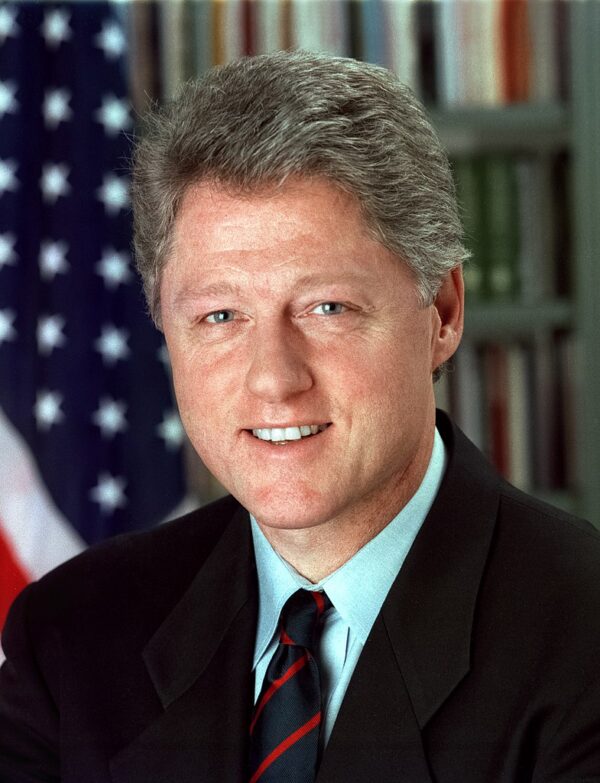

Unlike Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump, Biden has not launched a presidential peace plan to resolve the dispute between Israel and the Palestinians. Instead, Biden has focused on improving the Palestinian economy and Israel’s security cooperation with the Palestinian Authority.

Much to the relief of the Palestinians, the Biden administration has restored the annual $500 million aid package to Palestinian institutions. But the PLO mission in Washington, D.C., which was closed by the Trump administration, remains shuttered.

In keeping with Israel’s demand, Biden has not reopened the U.S. consulate in Jerusalem, a source of anger in Palestinian circles. But the Office of Palestinian Affairs at the U.S. embassy in Israel now reports directly to the State Department rather than to the embassy in Jerusalem.

The Palestinians are additionally upset by an official U.S. report that the Palestinian American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was accidentally rather than deliberately killed by an Israeli soldier in the West Bank.

Last month, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs Barbara Leaf urged Israel to avoid taking unilateral steps that could damage prospects for a two-state solution. In particular, she referred to a settlement construction plan in the E1 area of the West Bank, near Jerusalem, that would essentially undermine the possibility of a contiguous Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.

On July 4, Israel announced that hearings related to this controversial project would be delayed until September 12. In all probability, Israel will eventually build new settlements in the E1 sector.

In Jeddah, Biden will apparently ask Saudi Arabia to increase oil production so as to lower prices, which have reached unprecedented heights in the United States since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24.

Before his election as president, Biden blasted Saudi Arabia as a “pariah” nation that flouts human rights and whose leadership lacks redeeming social values. Outraged by the Saudis, Biden ordered the Central Intelligence Agency to release a report blaming the crown prince for the gory death of Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul in 2018.

Three years on, Biden will have to exercise much greater diplomacy and pragmatism to advance U.S. interests in the Arab world.