Joe Biden is acutely aware that his phased plan to end the Israel-Hamas war in the Gaza Strip may well be stillborn, at least for now.

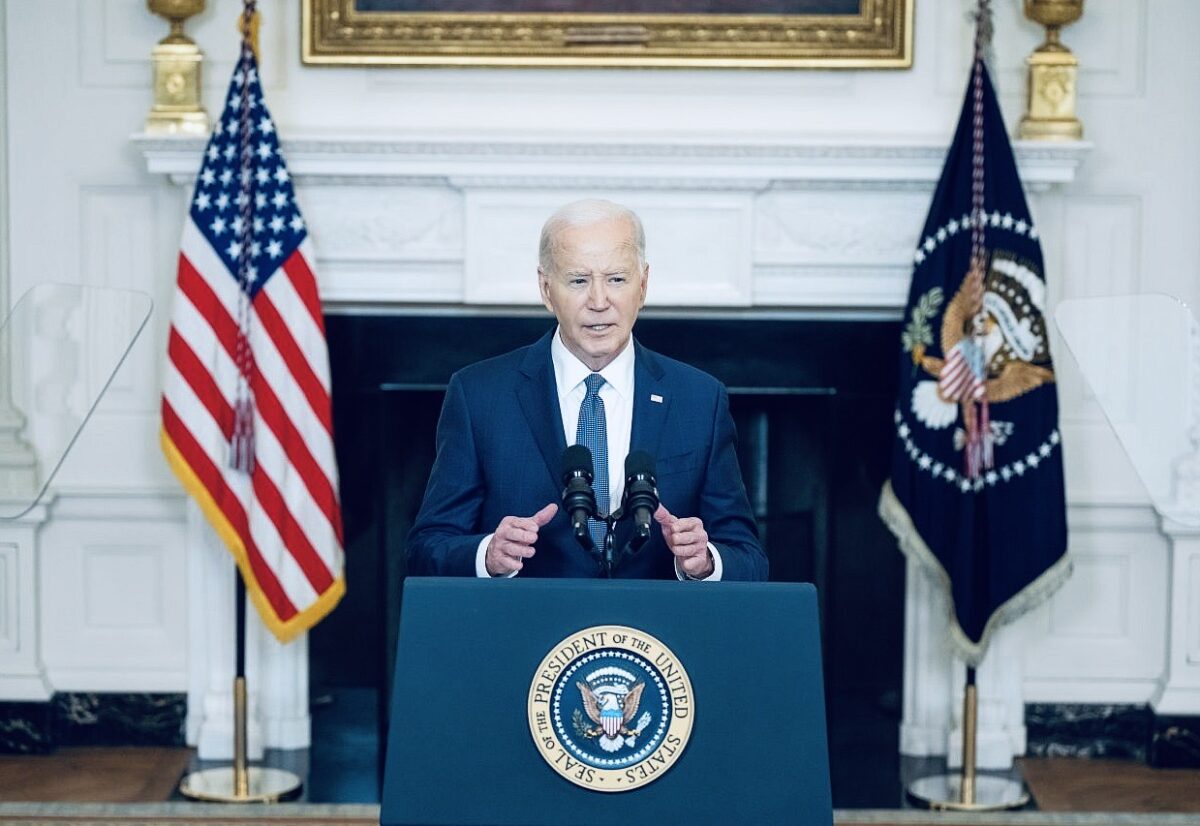

“I know there are those in Israel who will not agree with this plan and will call for the war to continue indefinitely,” he said as he outlined its provisions on May 31 in a speech from the White House.

Biden’s roadmap calls for the release of Israeli and foreign hostages, a lasting ceasefire after a full Israeli withdrawal from Gaza, and the reconstruction of the coastal enclave shattered by Israel’s air and ground offensive.

The U.S. president suggested that his roadmap to peace rests on an Israeli proposal, which Hamas roundly rejected recently. In fact, Biden has misrepresented Israel’s proposal by a considerable degree, which explains why Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has dismissed it as a “non-starter.”

However, Netanyahu’s senior adviser, Ophir Falk, softened Israel’s stand when he told the Sunday Times newspaper that Israel has not formally rejected Biden’s plan. “It’s not a good deal, but we dearly want the hostages released, all of them,” he said in a “yes, but” statement. “There are a lot of details to be worked out and that includes there will not be a permanent ceasefire until all our objectives are met.”

Two far-right ministers in Netanyahu’s coalition, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, threatened to quit if he accepts Biden’s proposal. With 14 Knesset seats, they can bring down his government. This would force Netanyahu to call a new election, which he may well lose.

Yair Lapid, the former prime minister and the leader of the centrist Yesh Atid Party, urged Netanyahu to embrace the plan, as did tens of thousands of Israelis at a rally in Tel Aviv on June 1.

With a U.S. presidential election looming, Biden has come under intense pressure from left-of-center elements in the Democratic Party and Arab American voters to stop the war, which erupted last October.

In his response to Biden on June 1, Netanyahu declared, “Israel’s conditions for ending the war have not changed. The destruction of Hamas’ military and governing capabilities, the freeing of all the hostages, and ensuring that Gaza no longer poses a threat to Israel.”

“Israel will continue to insist that these conditions are met before a permanent ceasefire is put in place,” he added. “The notion that Israel will agree to a permanent ceasefire before these conditions are fulfilled is a non-starter.”

On June 3, Netanyahu elaborated on his position. “The claim that we agreed to a ceasefire without our conditions being met is incorrect,” he said, noting that Biden’s plan is “incomplete.”

Addressing this theme, Defence Minister Yoav Gallant asserted on June 2 that the war will not end until Hamas is dismantled militarily and politically. He said that Israel is trying to find a new Palestinian governing authority to supplant Hamas.

Hamas, on the other hand, reacted positively to the Biden plan, saying it it ready to deal “constructively” with it if it is based on a complete withdrawal of Israeli forces from Gaza, a permanent truce, a “serious prisoner exchange,” and the return of nearly two million displaced Palestinians to their homes.

It remains to be seen what effect Netanyahu’s tacit rejection of Biden’s plan will have on Israel’s pivotal relationship with the United States, its chief ally and arms provider. It may well create a serious rift between Biden and Netanyahu, the seeds of which were planted years ago when they sharply disagreed over the issues of Palestinian statehood and the presence of Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

Biden, a longtime ally of Israel, initially supported Israel’s war aims and brushed off international calls for an immediate ceasefire. But as the death toll in Gaza climbed to unprecedented heights, the humanitarian crisis intensified, and open dissatisfaction with U.S. policy emerged in the Democratic Party, the Biden administration had a change of heart.

Biden announced his peace plan just days after Hamas and Israel hardened their respective positions.

Hamas advised mediators in Egypt and Qatar that it would not return to negotiations for a hostage/Palestinian prisoner deal unless Israel completely ceased its offensive in Gaza.

In a highly emotional meeting, Netanyahu’s national security advisor, Tzachi Hanegbi, told the relatives of hostages that the Israeli government will not agree to cease hostilities in exchange for their release. “We have to keep fighting so that there won’t be another October 7,” he said in a reference to Hamas’ massive attack, which resulted in the deaths of roughly 1,200 Israeli civilians and soldiers in southern Israel and the abduction of some 250 hostages.

On May 29, Hanegbi said that military operations in Gaza will continue at least until December. “We expect another seven months of combat to shore up our achievements and realize what we define as the destruction of Hamas’ and Islamic Jihad’s military and governing capabilities.”

It is unclear why he believes that Israel requires seven more months to achieve these interlocking objectives. But on the day he spoke, Israel gained control of the Philadelphi corridor — which demarcates Gaza’s border with Egypt and under which Hamas has smuggled weapons and munitions — and Israeli troops continued fighting in Rafah, Hamas’ last urban stronghold, and in the Jabaliya refugee camp.

It was against this backdrop that Biden disclosed his plan.

“It’s time for this war to end, for the day after to begin,” he said, claiming that Hamas is no longer “capable of carrying out another October 7.”

“This is truly a decisive moment,” he went on to say. “Israel has made (its) proposal. Hamas says it wants a ceasefire. This deal is an opportunity to prove whether (Hamas) really means it.”

Biden’s National Security Council spokesman, John Kirby, said on June 2 that the United States has “every expectation” that Israel will “say yes” to the proposed deal if Hamas accepts it.

Biden’s plan consists of three parts, all of which are ultimately connected.

The first phase would consist of a ceasefire lasting about six weeks, the pullout of Israeli forces from Gaza’s populated arises, and the release of elderly and female hostages in return for the release of hundreds of Palestinian prisoners.

During the second phase, all the remaining hostages would be released and Israel would withdraw from Gaza. It is unclear what authority would rule Gaza after the war, which means that Hamas may well fill the power vacuum. This would be a major strategic setback for Israel after almost eight months of warfare and the deaths of neatly 300 Israeli soldiers.

Biden admitted there are still “a number of details to negotiate” to advance the second part of the agreement.

In the third phase, the remains of deceased hostages would be handed over to Israel and a reconstruction period of up to seven years would commence in Gaza, many of whose buildings and much of whose infrastructure have been levelled.

Only hours before Biden made his announcement, Israel wrapped up its third clearing operation in the Jabaliya refugee camp after Hamas had managed to regroup. Israeli soldiers came under heavy fire, but killed 500 to 600 Palestinian combatants, demolished yet more tunnels and recovered the corpses of seven Israeli hostages.

Meanwhile, Israeli armored column reached the center of Rafah, killing some 300 Palestinian fighters in what Israel said was a limited and targeted operation.

The United States opposed the invasion of Rafah, saying it would cause the deaths of far too many civilians. Israel said that about one million Palestinians have been evacuated from Rafah under its supervision to safer areas north of the city.

Judging by the current state of the war, Israel still has long way to go before it achieves a semblance of victory in Gaza. Which is why Biden’s plan may not be implemented until Israel defeats Hamas.