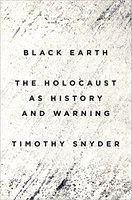

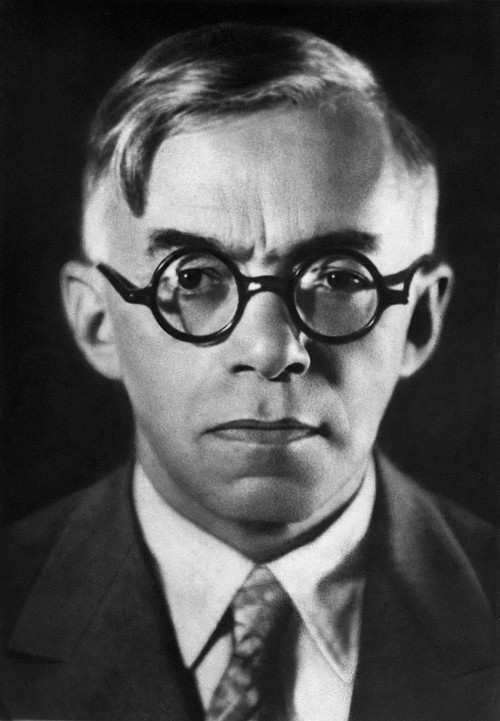

The Holocaust has been explored and analyzed ad infinitum by historians. Is there really anything new to be learned? The short answer is yes, judging by Timothy Snyder’s masterful Black Earth: The Holocaust As History And Warning (Tim Duggan Books).

Snyder, a Yale University professor whose last book was Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, identifies, clarifies and illuminates an important dimension of the Holocaust in his latest work.

As he puts it, “Not only the Holocaust, but all major German crimes took place in areas where state institutions had been destroyed, dismantled or seriously compromised. The German murder of five and a half million Jews, more than three million Soviet prisoners of war, and about a million civilians in so-called partisan operations all took place in stateless zones.”

By his definition, stateless zones existed in German-occupied countries — parts of the Soviet Union, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Greece and the Netherlands –where national sovereignty and bureaucracies had collapsed, leaving the field open to Nazi murderers and local collaborators. “Once a Jew lost access to a state he or she lost access to the protection of higher authorities and lower bureaucrats,” he explains.

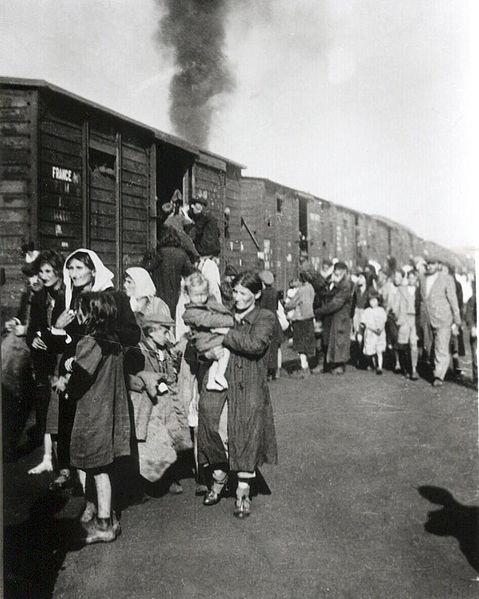

As he points out, it was no coincidence that German Jews, comprising three percent of the Holocaust’s victims, were invariably killed not in Germany but in chaotic locales outside its borders. From the autumn of 1941 onward, German Jews were deported to “bureaucracy-free zones” in Eastern Europe. “The killing sites of German Jews were places such as Lodz, Riga and Minsk.”

By 1942, 1.3 million of 3.3 million Polish Jews had been murdered in three facilities — Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor. Snyder speculates that the mass roundups and deportations of Jews in the Warsaw ghetto in the summer of 1942 were prompted by severe food shortages. By 1945, more than 90 percent of Polish Jews had been slaughtered.

Proceeding further, Snyder explains why three-quarters of the Jews in the Netherlands and Greece were murdered, compared to 25 percent in France, where a sense of order reigned.

“The Netherlands was, for several reasons, the closest approximation to statelessness in western Europe,” he writes. With the Dutch government and Queen Wilhelmina having gone into exile, the Netherlands’ sovereignty was compromised, its civil service was effectively decapitated and its police force was purged.

“Uniquely in western Europe, the SS sought and attained fundamental control of (Holland’s) domestic policy,” he says. This accounts for the fact that Amsterdam was the only western European city where the Nazis considered creating a ghetto.

Greece, too, lost its sovereignty after the German occupation. “No Greek government exercising any real authority was formed during the war,” says Snyder. The Nazis were thus free to deport the 43,850 Jews of Salonika.

With notable exceptions, the situation was remarkably similar in Hungary. The pro-German regime in Hungary, led by Miklos Horthy, persecuted Hungarian Jews, but they were physically safe until Germany invaded Hungary on March 19, 1944. From May to July, with Hungary under the Nazi boot, 437,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz Birkenau.

The 50,000 Jews of Bulgaria fared much better. Not a single Jew was deported to a death camp in Poland. Bulgaria — a German ally — was not occupied. And the Bulgarian elite, its anti-Jewish impulses notwithstanding, protected Jewish citizens. Bulgaria, however, allowed the Germans to deport the 13,000 Jews of Macedonia and Thrace, which were under Bulgarian occupation.

Romania, Germany’s major military ally on the Soviet front, was the only other country apart from Germany which directly subjected Jews to mass murder. Romania, with a deeply ingrained tradition of antisemitism, carried out massive pogroms in territories it had lost to or had gained from the Soviet Union.

Yet Romania’s fascist leader, Ion Antonescu, refused to deport Romanian Jews to extermination camps. He feared that their removal would benefit the ethnic German minority and thereby increase Germany’s influence in Romania. According to Snyder, Antonescu’s Jewish policy was also influenced by Germany’s refusal to hand over northern Transylvania to Romania. All told, Romanian forces managed to murder 280,000 Jews, yet two-thirds of the Jewish community survived.

In states allied with Germany, where major political institutions remained intact, Christians who protected Jews were rarely punished. Bulgaria and France come to mind in this respect. But in Poland and western areas of the Soviet Union, where chaos was common, the punishment for aiding Jews was death. “In general, the only people who could rescue Jews in large numbers were those who had some direct connection to a state and some authorization to dispense its protection,” he notes, citing the rescue efforts of the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg in German-occupied Hungary.

Although the Nazi regime was profoundly antisemitic, Germany had no plan for the mass murder of Soviet Jews when it invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Nazi mobile killing squads, known as Einsatzgruppen, had orders to kill Jews, but not to shoot them all, Snyder claims. At the outset, the main task of the German armed forces was to demolish the Soviet communist state. Only after the January 1942 Wannsee conference would Germany focus its attention on the systematic destruction of European Jewry.

Snyder argues that the Einsatzgruppen, though the first to massacre Jews on an industrial scale, played second fiddle to German policemen in terms murdering Jews. German soldiers, he adds, were also culpable, having killed and having assisted the police and Einsatzgruppen in the killing of Jews.

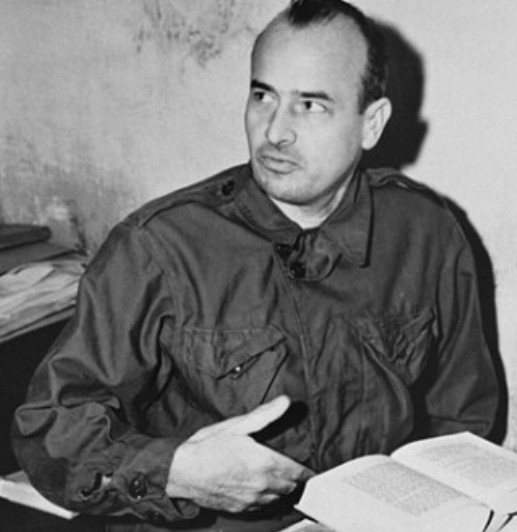

One million Jews in the Soviet Union already had been killed when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and brought the United States into World War II. In response, Adolf Hitler, the Nazi fuhrer, declared war on the United States and repeated his “prophecy” of January 1939 to annihilate Jews should a European war break out. Upon hearing Hitler’s threat, Hans Frank, the German governor of occupied Poland, told his staff, “We must annihilate the Jews wherever it is possible.”

As Snyder writes in the first few pages of Black Earth, Hitler’s rabid antisemitism was deeply woven into his psyche. The Jews, he claimed, were a “spiritual pestilence,” worse than the Black Death. The only way to remove this plague was to eradicate it at the source. Hitler remained firmly wedded to this view until the very end. Jews were the “world poisoners of all nations,” he said on April 29, 1945, a day before he committed suicide in his Berlin bunker. He was certain of his legacy: “I have lanced the Jewish boil. Posterity will be eternally grateful to us.”

By Snyder’s reckoning, the Holocaust began in Lithuania and Latvia, where local collaborators, egged on by the Germans and incensed by the participation of some Jews in the Soviet occupation of their countries, committed widespread atrocities. Germany’s chief collaborator in Latvia, Viktors Bernhard Arajs, a lawyer, formed a special militia to perpetrate pogroms. In the summer of 1941, his trained killers shot 22,000 Jews and assisted in the murder of 28,000 more.

In the Soviet Union — where antisemitism had been classified as a crime — Snyder says there was more collaboration than in Poland. “No matter where the Germans arrived in the Soviet Union, the result was essentially the same. The mass murder of Jews was planned by the Germans but achieved with much assistance from people of all Soviet nationalities.”

In Belarus, for example, communists and members of communist youth groups joined the police in the mass shootings of Jews.

Jews were at the mercy of the spurious “Judeobolshevik myth” in all these places. Nazi propaganda exploited the theme that Jews had imposed communism on Russia and had collaborated with the Soviet Union after its invasion of Poland and the Baltic states in 1939 and 1940. Antisemitic nationalists seized on it to settle scores with Jews.

This myth gained widespread currency in Poland, particularly after the death of its ruler, Jozef Pilsudski, in 1935. It was propagated, in the main, by the National Democrats, Pilsudski’s old enemy. Post-Pilsudski governments, seeking to undermine the appeal of the National Democrats, adopted antisemitic policies and encouraged Jewish emigration to Palestine and the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar.

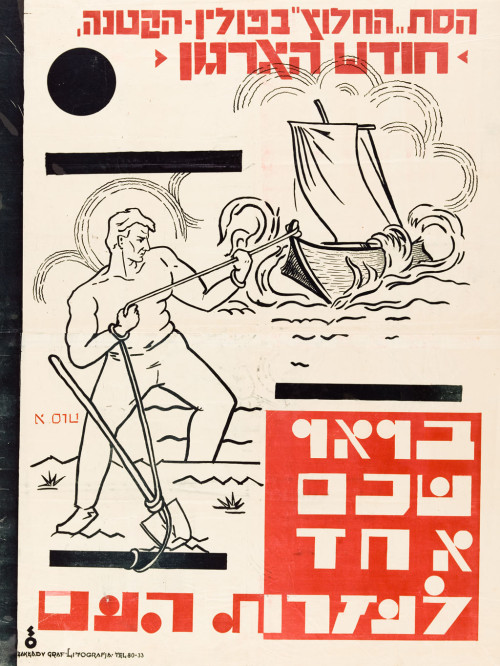

“Warsaw wanted both massive emigration of Jews from Europe and a Jewish state in Palestine,” Snyder says.

Polish diplomats urged Britain to ease immigration restrictions and create a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In 1937, Poland offered the Haganah — the chief Jewish self-defence force in Palestine — arms and training. The Poles extended the offer to the Irgun, the military wing of the right-wing Zionist Revisionist movement.

There was a convergence of interests between Poland and the Zionist Revisionists. Vladimir Jabotinsky, its leader, believed Jews should leave Europe en masse and create a Jewish state on both sides of the Jordan River. He thought that Poland should replace Britain as the mandatory power in Palestine.

Prior to these developments, Germany courted Poland. Hitler, in a conversation with Poland’s ambassador to Germany in 1934, described Poland as Germany’s “shield in the east.” In the following year, he proposed a joint German and Polish war against the Soviet Union, but the Poles preferred to maintain cordial relations with both sides. Germany, until 1937, continued to call for an alliance with Poland. With Warsaw having adamantly spurned Berlin’s overtures, Germany eventually turned to Moscow.

The non-aggression pact signed by Germany and the Soviet Union on the eve of World War II doomed Poland as well as its Jewish inhabitants. Poland was partitioned and the Jews were systematically murdered.

No optimist, Snyder is of the opinion that genocide could well rear its ugly head again. “There is little reason to think that we are ethically superior to the Europeans of the 1930s and 1940s, or for that matter less vulnerable to the kind of ideas that Hitler so successfully promulgated and realized,” he writes in a chilling observation.

Reminding us of Hitler’s thesis that Jews were a cancer to be excised, he warns that they may yet again be seen as a universal threat by “increasingly important political formations in Europe, Russia and the Middle East.”

It’s an apocalyptic notion, to be sure, but it may contain a kernel of the truth.