As almost everyone who watches newscasts knows, Donald Sterling, the elderly and foolish billionaire who is owner of the Los Angeles Clippers of the National Basketball Association, has become the object of intense – many would say excessive – media coverage.

Sometimes it seems that the story is getting more airtime on American networks like CNN than the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 or the kidnapping of hundreds of schoolgirls in Nigeria by Boko Haram — not to mention a civil war in Syria that has already cost some 150,000 lives.

The tape of a private phone conversation he had with a woman, variously described as a “girlfriend” or “mistress,” was posted on line and became the object of a firestorm. In the tape, Sterling, whose own basketball team is comprised of mostly Black payers, is heard telling the woman not to bring “Black people” to Clippers games.

The NBA is now trying to force him to sell the team.

Sterling insists he is not a racist, pointing to the fact that, as he put it, he’s the one that clothes and feeds his players — which made him sound all the worse.

On one level, this over-reported story may be, if not a tempest in a teapot, than perhaps one in a rain barrel. Even if Sterling loses his team, he will not end up homeless. His “amour,” too, has not suffered any losses. And the players will keep their jobs.

But does this sordid saga have any wider implications?

The mainstream media have carefully refrained from noting Sterling’s religion, though the Jewish press has made note of it. Sterling himself, in interviews, has brought it up, in order to defend himself.

What does this mean for Black-Jewish relations? Actually, not much.

Everyone in this tale is well-off, if not indeed very rich. Sterling, along with his wife and children, are extremely wealthy, and the African-American players on his team make more money than the vast majority of Americans of every colour and ethnicity.

Some of the potential African-American buyers of the Clippers — Earvin “Magic” Johnson and Oprah Winfrey have been mentioned — are also mega-millionaires.

We are talking about a very small stratum of the Black, and Jewish, population.

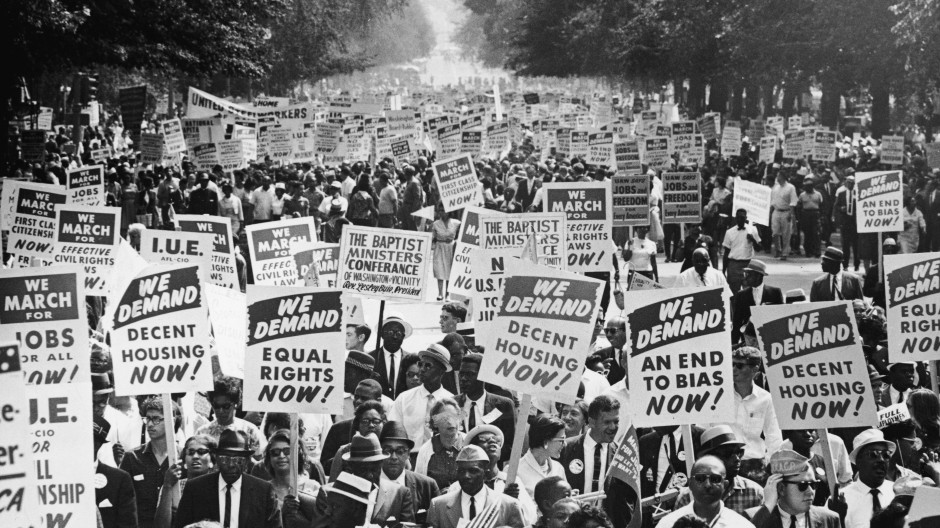

Most readers of this article will be aware that the apogee of the Black-Jewish alliance in the United States was during the Civil Rights movement, from the 1940s through the 1960s. Jews, who had suffered antisemitism and, in many cases, had lost relatives in Europe during the Holocaust, were acutely aware of the legal discrimination faced by African-Americans.

In southern states, “Jim Crow” segregation was legally enshrined, and Blacks were kept out of hotels, restaurants, housing and schools. They were even prevented from voting.

All of this was swept away by the 1970s — and Jews had played a major role in putting an end to it.

This happens to be the 50th anniversary of the Mississippi “Freedom Summer.” In 1964, the majority of African-Americans in Mississippi worked as farm laborers or as domestic workers, with typical wages of $3 per day. Labor unions did not exist. Efforts to change these conditions were met with legal repression as well as terrorist violence by the Ku Klux Klan, the White Citizens Council, and the state police.

That summer, more than 700 civil rights volunteers from the north, 90 percent of them white — and, by most estimates, at least a third of them Jewish — came to the state to help Blacks register to vote. Many of these young Jews, who ranged in age from 18 to 25, were from left-wing families. They were often attacked and beaten; two of them, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, were killed by the Klan. They wrote a heroic page in American history.

But things would change. Black nationalism, often tinged with antisemitism, replaced the older affinity between Blacks and liberal whites (a disproportionate number of whom were Jewish). In effect, the African-American and Jewish communities went their separate ways.

Ironically, when Blacks and Jews relate to each other nowadays, it is often in the context of wealthy Jews such as Sterling (and the many other Jewish owners of basketball and football franchises) employing African-Americans, or owning properties in Black neighbourhoods. It often leads to friction, though typically for economic, not political, reasons.

All of this is very far removed from the heyday of the Black-Jewish struggle against racism in the 1950s and 1960s.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.