Israeli filmmaker Michal Weits untangles her grandfather’s complex past as a state builder in Blue Box, a compelling 82-minute documentary that will be screened at this year’s Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 9-26.

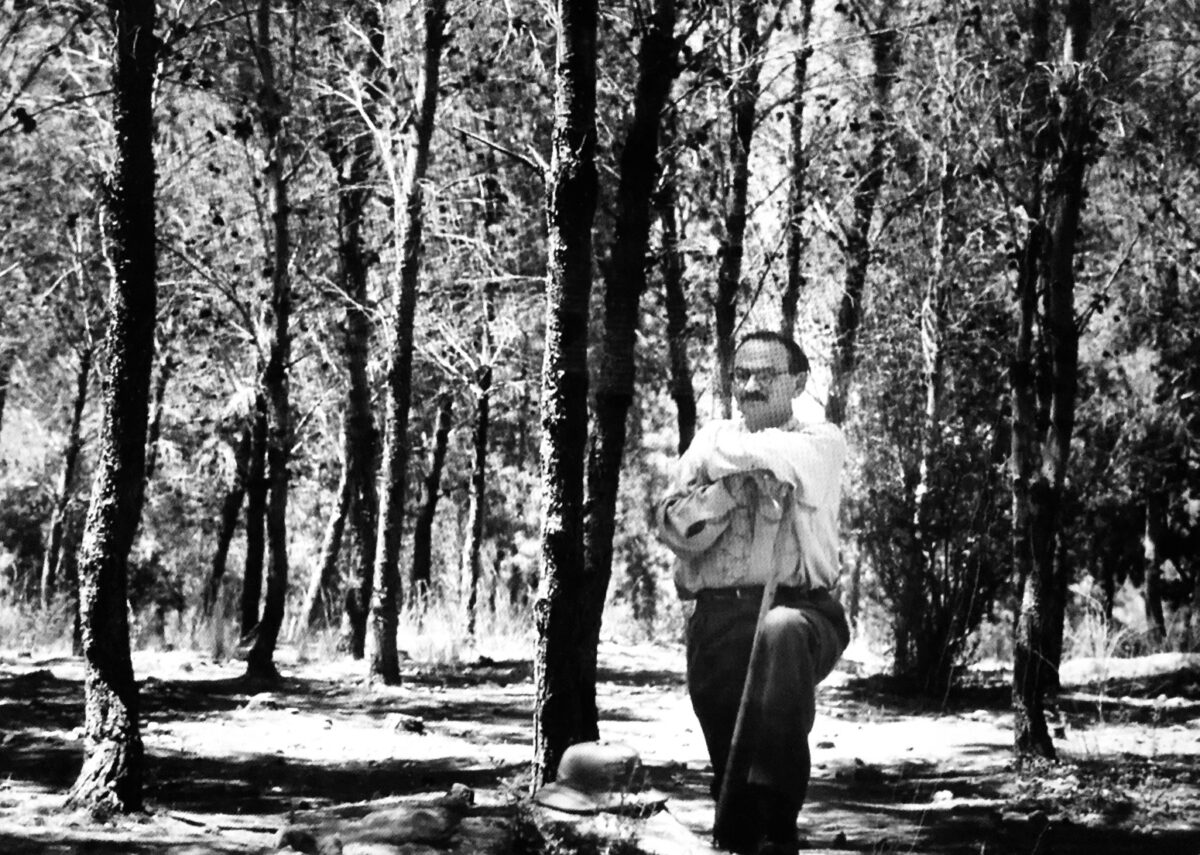

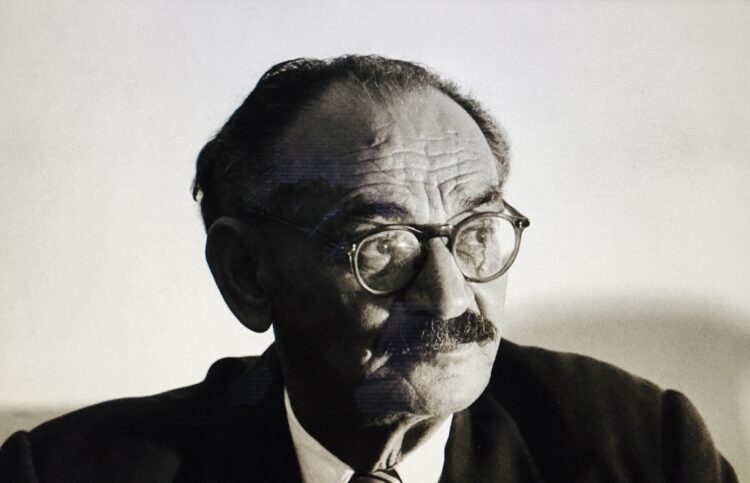

Joseph Weitz, the father of Israel’s forests, was the director of both the Jewish National Fund’s Department of Lands and Department of Afforestation. He held this important position from the early 1930 until the mid-1960s.

In this capacity, he purchased land from Palestinian Arabs, established new settlements, planted forests and resettled new Jewish immigrants in towns and neighborhoods that had been vacated by fleeing Arabs during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

A Zionist pioneer in every sense of the word, Weitz was a larger-than-life mythical figure whom Weits learned to love and admire as a man who turned “waste into woodlands.” Like some of the early Zionists, Weitz was faithful to the misleading slogan that Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land.”

For many years, Weits felt pride in his achievements, but after reading his voluminous diaries, which run to 5,000 pages, cracks in his hallowed image appeared. Blue Box is the story of her fascinating and disillusioning journey of discovery. It is supplemented by interviews with Weitz’s sons, grandsons and granddaughters.

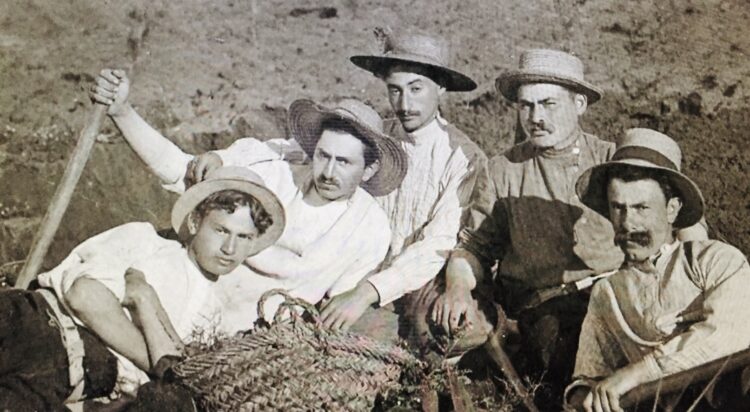

Weitz was born in the Russian empire in 1890 and arrived in Ottoman Palestine in 1908, when it was inhabited by 600,000 Muslim and Christian Arabs and 80,000 Jews. Like most of the newcomers, he spent his formative years there as an agricultural worker. In 1932, he was appointed to his pivotal positions in the Jewish National Fund.

Created in the first decade of the 20th century, the Jewish National Fund was an integral cog in the machinery of the Zionist movement in Palestine. Its primary mission was to buy and develop land, build settlements and thereby advance the momentum toward Jewish statehood.

Thanks to its ubiquitous blue donation boxes, which were widely distributed in the Diaspora, the Jewish National Fund raised funds for its varied activities. To Weits, the Jewish National Fund was the “first crowd-funding organization.”

Weits suggests that her grandfather was a driven and dedicated Zionist. “We must wheel and deal to obtain the land where the Arabs live,” he wrote in his diary.

He usually purchased land from effendis, or absentee landlords, in the Arab world. In most cases, the poor Palestinian peasants who worked the land were evicted, causing Weitz twinges of guilt and remorse.

He rationalized his feelings by reminding himself that the interests of the Jewish people came first and that these acquisitions would determine the borders of a future Jewish state. Yet he instinctively understood that the evictions left a deep wound and aroused bitterness and resentment among the masses of Palestinians.

Weitz believed there was no room for Arabs and Jews in a country as small as Palestine. As he wrote in his diary, “If the Arabs depart, the land will be vast and spacious. If Arabs remain, the country will be impoverished and cramped.”

To Weitz, the only solution was “a land with no Arabs.” Compromise was out of the question, as far as he was concerned. “Transfer them all,” he declared.

The Holocaust devastated Weitz, but he sought refuge in the notion that the development of the Yishuv would be “our revenge” for the deaths of six million European Jews.

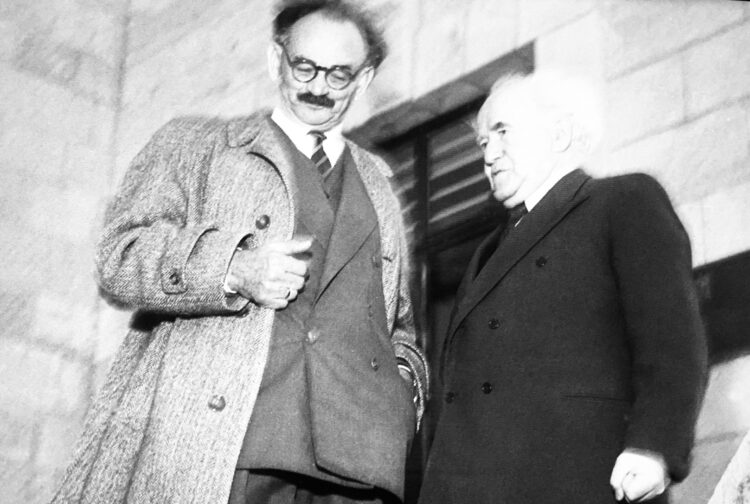

The mass flight of Palestinian Arabs from their homes in 1947 and 1948 pleased Weitz. More than 700,000 Arabs fled during the Arab-Israeli war, leaving 156,000 Palestinians within Israel’s borders. He urged Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, to demolish what remained of Arab villages, to settle Jews there, and to prevent Arab refugees from returning to their properties. He was certain that the fate of the refugees would determine Israel’s borders.

At Weitz’s recommendation, the Israeli government sold 250,000 acres of Arab land to the Jewish National Fund. It would be the biggest real estate transaction in Israel’s history. In 1950, the Knesset passed the Absentee Property Law, which legalized the property transfer and ensured that the refugees could not return.

Following the war, the Jewish National Fund planted 80 million trees throughout Israel. Some abandoned Arab villages were buried under a thicket of pine trees, Weits says.

As he aged, Weitz grew uneasy about the fate of the refugees. He thought they should be compensated for their losses. And he feared they would block a rapprochement between Israel and neighboring Arab states.

He did not rejoice in Israel’s Six Day War victory, claiming that Israel lacked the means to “absorb” the Palestinians of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The problem so depressed him that he advised the Israeli government not to take”decisive” steps in the occupied areas that would brand Israel as an “imperialist conqueror.”

Judging by the comments of his sons and grandchildren, Weitz’s checkered legacy has left his family uncomfortable. This is perfectly understandable. Weitz was an activist and a doer who had a profound influence on Israel and its protracted dispute with the Palestinians. Blue Box makes that abundantly clear.