One of the most disgraceful incidents in modern Poland took place in Kielce on July 4, 1946, when a mob murdered 42 Polish Jewish survivors of the Holocaust. The pogrom, a watershed event signifying the persistence of antisemitism in Poland, prompted tens of thousands of Jews to emigrate.

During the Communist era, this murderous incident was invariably suppressed, but it was never forgotten. In the past 25 years, with the rise of democracy in Poland, it has been a subject of heated debate.

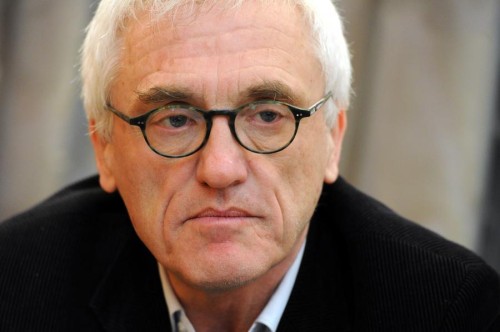

Bogdan Bialek, a Polish Catholic journalist from Kielce, has played a central role in keeping the memory of the pogrom alive. Bialek’s noble efforts are recognized in Bogdan’s Journey, a deeply-felt and uplifting documentary by Michael Jaskulski and Loewinger.

Scheduled to be screened at the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Center’s Al Green Theater on Sunday, November 5 at 7:30 p.m, it’s presented by the Toronto Jewish Film Society in partnership with the Polish-Jewish Heritage Foundation of Canada during Holocaust Education Week.

The film, spanning a period of almost two decades, challenges the fanciful notion of right-wing Polish nationalists that the pogrom — the first in postwar Europe — was not the work of Poles. As the evidence strongly suggests, it was carried out by Polish policemen, soldiers and factory workers. The case is strengthened by the commentary of a Polish historian and the testimonies of survivors and witnesses.

Bialek, a man on a mission, wants Poles to come to grips with the bitter truth.

He launched his campaign 17 years ago, when friends, acquaintances and followers joined him on a procession to Kielce’s Jewish cemetery, where the victims of the pogrom are buried. His intention was to pray for the dead, honor their martyrdom and remind the citizens of Kielce that this crime, like the 1941 pogrom in Jedwabne, was committed by Poles.

Some Poles, of course, are still in a state of denial, claiming it was perpetrated by the Communist secret police. Others maintain that Jews brought it upon themselves. Still others are certain that anti-Jewish animus is an alien phenomenon in Poland. As an older woman says, “It’s wrong to accuse Poles of antisemitism.”

Not surprisingly, the survivors tell a completely different and far more plausible story.

“They came to murder,” recalls one survivor. “I couldn’t believe they were humans,” says another one, still shocked by the sheer suddenness and brutality of the attack.

The pogrom was sparked by a despicable lie — the claim by a Polish boy that he had been held captive in the basement of a building owned by a Jew.

As angry Poles gathered around a Jewish community center at 7/9 Planty Street, they shouted, “Beat the Jews.” Soldiers and police broke into the building, killing and wounding scores of people.

Jan Gross, the Polish American historian, wrote about the pogrom in Fear, a book that stirred controversy in Poland. As he toured the country promoting his book, detractors accused him of fanning the flames of antisemitism.

During the course of the film, Bialek visits Israel to meet Jews of Polish origin. He talks to a man who lost his eyesight during the pogrom and to a woman who inaccurately claims that all Poles were antisemitic during the Communist era.

Bialek is portrayed as a person who promotes Polish-Jewish dialogue by organizing workshops on Jews, prejudice and stereotypes. In addition, he’s seen participating in a ceremony marking the inauguration of a memorial dedicated to the victims of the pogrom. Bialek is disappointed that local newspapers fail to cover the event. In another segment of the movie, a group of Poles cleans a neglected Jewish cemetery near Kielce, proving that Bialek is in good company.

In the next few scenes, a Jewish survivor from Israel visits Kielce and receives a warm welcome, the son of a Polish perpetrator expresses shame and anger over his father’s actions in 1946, and a Polish family accepts a medal from Yad Vashem — the Holocaust research and educational center in Israel — on behalf of their late grandparents, who were granted Righteous Gentile status.

A viewer is left with the impression that Kielce is honestly grappling with its shameful past, but that it will be haunted by the infamy of the pogrom indefinitely.