The 20th century brought calamity and renewal to Germany, transforming it from a military aggressor into a pillar of European democracy.

Germany suffered territorial losses and hyperinflation following its defeat in World War I. The Weimar Republic was a time of hope, but the Depression paved the way for Adolf Hitler’s racist regime, which persecuted its Jewish citizens and triggered World War II.

The war emboldened the Nazis to murder Jews on an industrial scale during the Holocaust, but it also resulted in the deaths of millions of Germans. Germany’s unconditional surrender in 1945 led to its division into two separate countries, West Germany and East Germany. With reunification in 1990, Germany healed itself.

Konrad Jarausch, a professor of European civilization at the University of North Carolina, charts the tumultuous trials and tribulations of the German people in his first-rate book, Broken Lives: How Ordinary Germans Experienced the 20th Century, published by Princeton University Press. He draws on the memoirs of dozens of Germans who were born in the 1920s and who witnessed these cataclysmic changes.

Whatever their religion, class or status, Germans who came of age during this era inherited certain traits — hard work, discipline, punctuality and respect for authority — that are quintessentially Germanic. But as Jarausch points out, Germans had always been divided along political and social lines. The nationalist outlook appealed to land owners, officers in the armed forces, public officials,, traditional Protestants, and even some artisans and farmers. Liberals were drawn from the middle-class. Catholics defended their faith in an increasingly secular society. Industrial workers gravitated toward the labor movement.

With the formation of a united Germany in 1871, Jews were finally granted civic rights, but the rise of racial rather than religious antisemitism forced them to consider whether they wished to maintain a separate identity or try to blend in with Christians. The majority of Jews opted for compromise, choosing to be Germans of the Jewish faith. Highly-assimilated Jews who chose conversion were chastened by the knowledge that hardcore antisemites would never accept them as true Germans.

The ascendancy of the Nazi movement created conflict within many families, but with Hitler’s accession to power in 1933, public dissent was no longer possible or advisable. In schools, students were indoctrinated with nationalist and racist ideas. Nazi influence isolated Jewish pupils, making them targets of abuse and discrimination. Most Jewish students were expelled from schools in 1936, compelling them to attend Jewish educational institutions.

Few young Germans questioned the status quo. “The combination of nationalist home, Nazified school, and Hitler Youth indoctrination made the majority obedient tools of Nazi repression and aggression,” he writes.

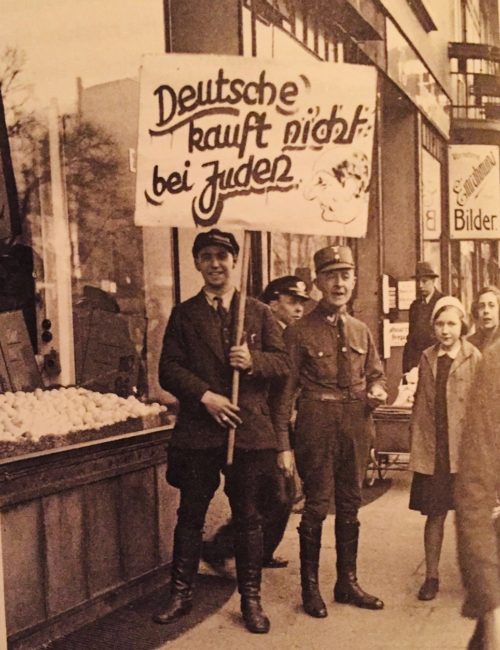

The passage of antisemitic edicts, principally the 1936 Nuremberg Laws, erased decades of progress toward Jewish emancipation and completely excluded Jews from the German “folk” community. And while Nazi pressure forced Christians to sever ties with Jews, a courageous minority of anti-fascists maintained such relationships.

Two-thirds of Jews emigrated, leaving the remainder to deal with the terrible consequences of Nazi hostility. Germany closed the door to further Jewish emigration by banning it in October 1941. From that point onward, Jews were subjected to petty regulations, evictions from their homes, segregated housing, and deportations to ghettos and concentration camps in Poland and the Baltic states.

Vocal opponents of the regime were imprisoned, sent to camps like Dachau and Buchenwald, and executed. Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg, the army officer who joined a 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler, was shot by firing squad. Still other anti-Nazis went into internal exile.

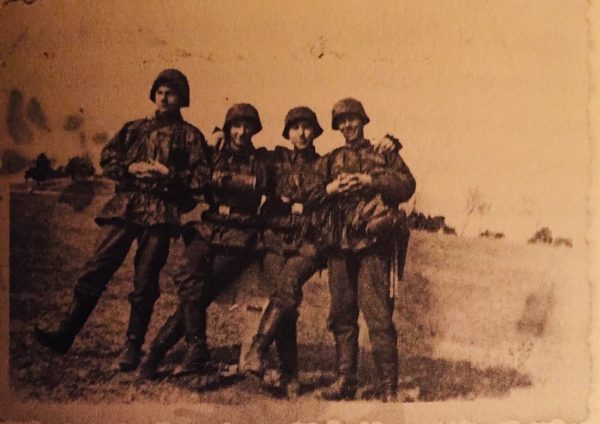

The outbreak of World War II upended the lives of young men. Conscripted into the armed forces, they had to interrupt their education, careers and romantic relationships. Nazi fanatics, however, gladly volunteered for the Waffen SS. Most Wehrmacht soldiers, having been thoroughly brainwashed, thought they were defending the fatherland or Germany’s very existence. Open criticism of the war, attempts at sabotage or desertion were ruthlessly suppressed.

German soldiers began to question the purpose of the war as Germany’s impending defeat loomed. “The exploitation of slave laborers, the bloody suppression of partisans and the racist persecution of Jews could no longer be ignored and raised moral questions about the justification of German actions,” says Jarausch. “While some fanatics continued to cling to their nationalist faith, many soldiers began to disassociate themselves from the ‘damned hoax’ of a bankrupt regime.”

With battles raging across Europe, women became the backbone of the home front. Overwhelmingly supporting the war, women filled jobs once reserved for men. About 1.4 million females served in the military in administrative, communication and air raid defence roles. A small cadre of women, such as the notorious Ilse Koch, were concentration camp guards. Some unmarried women joined the “fountain of life” program, giving birth to racially “pure” Aryan babies to counteract the falling birthrate.

Tens of thousands of women perished in the Allied bombing raids of German cities. Upwards of one million women died during the mass flight of civilians from eastern German lands captured by the Red Army. Up to two million women were raped by Russian troops seeking vengeance for German atrocities.

Jarausch believes that more “ordinary Germans” participated in the Holocaust than is commonly assumed, but that fewer were involved than some critics claim. “At the core of the mass murder were the direct killers in the SS, Einsatzgruppen, Wehrmacht, and ethnic auxiliaries who were helped by merciless bureaucratic organizers and cheered on by racial ideologues.”

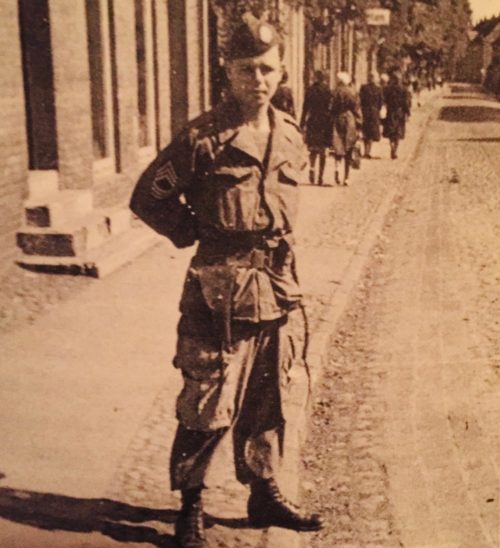

With the collapse of the Third Reich, Germans were burdened by a belief that the future held no hope. Ten million German troops languished in prisoner-of-war camps, the last ones ones being released from the Soviet Union in 1955. German Jewish refugees played an important role in the establishment of the Allied occupation. Ethnic Germans, expelled from former German territories or from foreign countries, streamed into occupied Germany.

Given the labor shortage after the war, German women took part in the rebuilding of devastated cities. They also assumed jobs once held by men, running streetcars and baking bread.

Housing was scarce, since many apartment buildings had been destroyed and German refugees kept arriving.

De-Nazification efforts were stricter in the Soviet zone of occupation, but on both sides of the political divide Nazis seamlessly changed sides and embraced the ideology of the respective occupying powers.

Demoralized by the extent of the urban destruction, some Germans, including Nazi perpetrators, left Germany altogether, finding new homes abroad. Jews in refugees camps departed as well.

Members of the postwar generation, growing impatient with their parents’ refusal to admit personal culpability for Germany’s crimes, adopted rebellious attitudes and beliefs.

The Federal Republic of Germany, founded in 1949 as a merger of the U.S., British and French occupation zones, instituted strong constitutional safeguards against a resurgence of dictatorship. The principal founders of the republic, Konrad Adenauer, Kurt Schumacher and Theodor Heuss, sought to restore the rule of law, alleviate suffering and provide prosperity.

“The removal of rubble, the gathering of crops, the reconstruction of transport, and the rebuilding of housing required great physical effort to reassemble an infrastructure for normal existence,” says Jarausch, adding that these visible achievements restored German self-confidence.

In particular, the postwar boom reshaped West Germany, where the benchmark of affluence was the ownership of a car for business and/or pleasure.

Three decades of economic growth not only rehabilitated a ruined nation, but also “propelled its citizens into an affluent consumer society far beyond Weimar or the Third Reich,” he notes.

Restitution payments to Holocaust survivors by the West German government showed that the elite accepted moral responsibility for Nazi crimes. “Although Adenauer appealed to a centre-right electorate, he understood that integration into the West would only succeed if he also expressed contrition for German crimes and offered restitution to Israel and the Jewish community,” says Jarausch.

In this respect, “the incontrovertible evidence of mass murder through survivors’ testimonies, documentary films and literary representations discredited antisemitism in public,” he adds.

Over time, a consensus emerged that the Third Reich had been “an abject failure, that war was to be avoided, and that the Communist alternative (in East Germany) remained unacceptable.”

These ideas produced what Jarausch describes as “the chastened Germans of today.” As he elaborates, “The horrific experiences and troubling memories of the twentieth century have transformed the majority of Germans, making them profoundly different from their European neighbors.”

In short, the lessons of the past have turned many Germans into “sincere democrats and pacifists” who abhor war, totalitarianism and discrimination based on racial differences.

One can only hope that Jarausch is correct. Certainly, he makes a convincing case for this argument in Broken Lives, one of the finest books I have read about Germany.