The biggest threat to Israel’s long-term stability is its lack of a formal constitution, says Arye Carmon, the founding president of the Israel Democracy Institute, which is dedicated to promoting and strengthening democratic values in the Jewish state.

Carmon, a philosopher and historian, expounds on this theme in Building Democracy On Sand: Israel Without A Constitution, published by Hoover Institution Press.

In his view, Israeli democracy is “fragile and wounded,” requiring a constitution to shore it up.

Israel is a modern state with a list of stellar achievements to its credit. Its institutions and agencies, including the Knesset, function reasonably smoothly. Its high-tech economy thrives and is the envy of neighbors. Its armed forces are among the world’s finest. Its revival of Hebrew as a working language is impressive.

And yet, as Carmon argues in this cogent volume, Israel is “riddled with weaknesses” crying out for repair. He contends that Israeli democracy is still in its “formative stages” due to the absence of a constitution. In the meantime, he notes, “basic laws” serve as a provisional constitutional framework.

He also believes that Israel needs a bill of rights to “safeguard the freedoms of its citizens and underpin the norms of its civil society.”

Without a constitution, Israel lacks “the consensual underpinnings that stabilize governance and enable the inclusion of diverse outlooks and beliefs.”

The principle of inclusion, a pillar of democracy, has been challenged by the reality of exclusion, he says, referring to the much-resented monopoly Orthodox Judaism enjoys over religious matters in Israel.

Drawing a link between religion and democracy, Carmon writes, “The role of religion in Israeli public life undoubtedly plays a major role in the weakening of the secular foundation of Israeli democracy and culture. The glaring absence of a constitution is crucial to the way religion has worked its way into public spaces, where it is threatening Israel’s democracy.”

He adds that the lack of a “constitutional arrangement” over the matter of separation of religion and state has produced volatility.

“For various reasons, Israel has ignored the need to define and establish the place of religion in public life,” he says. “This has generated a deepening conflict of identities over time. Thus, we live in a state whose identity is defined as ‘Jewish and democratic,’ but the question of who defines its Jewishness is the subject of profound disagreement.”

He ascribes the problematic relationship between Judaism and democracy to early Zionist leaders. As he puts it, “The Zionists rebelled against the foundations of Judaism, when instead they should have found new ways to embrace the richness of Jewish history and civilization. They should have found a way to develop new, free interpretations of Jewish liturgy, philosophy and texts … This would have validated the secular nature of the Zionist revolution while also solidifying the place of the Jews as a national collective.”

What emerged in Israel was an Orthodox monopoly on Jewish life and observance. “In retrospect, it is easy to understand why multicultural and pluralistic interpretations of Judaism lack legitimacy in Israel. It also becomes clear why Conservative and Reform Jews — the backbone of Judaism inherited the United States — are the subject of formal boycotts by the religious authorities in Israel.”

Zionism tragically failed to build a democracy that tolerates a collective Jewish identity based on a democratic and humanistic foundation, he concludes.

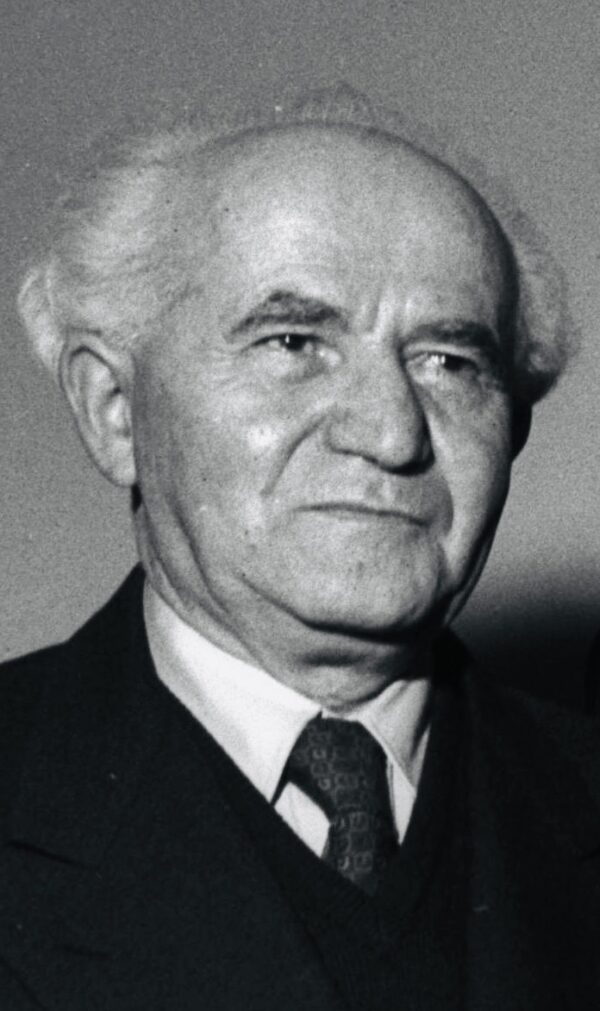

In his opinion, the Zionist movement missed an historical opportunity to formulate a constitution. The 1949 election in Israel was supposed to elect representatives to a national assembly charged with producing a constitution in that year. But Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, was doubtful whether a constitution would be feasible or even worth the effort.

With so many nation-building challenges requiring his prompt attention, he apparently believed that the writing of a constitution would distract him and tie his hands.

Ben-Gurion never got around to this task, leaving Israel without a constitution and producing the problems that Carmon elucidates in Building Democracy On Sand.