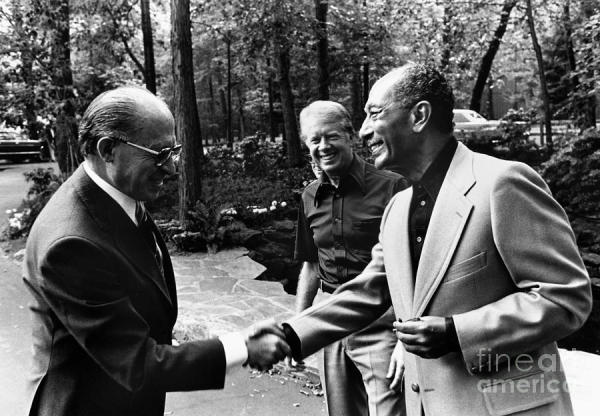

For nearly two weeks in 1978, the Middle East metaphorically held its breath as the leaders of the United States, Israel and Egypt attempted to make an historic break with the past. The Camp David summit brought together Jimmy Carter, Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat for the purpose of forging a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, on the one hand, and a framework for an agreement between Israel and the Palestinians, on the other hand.

The conference slid into crisis mode several times and almost collapsed, but thanks to Carter’s dedication and persistence, it was partially successful, inasmuch as it created the right conditions for a new era in Israel’s heretofore hostile relationship with Egypt. Camp David prompted Israel to grant the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip a form of autonomy, but it fell far short of statehood and was opposed by the Palestinian leadership in the PLO.

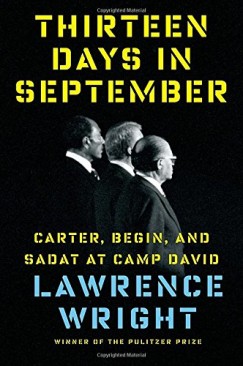

At this presidential retreat in the mountains of Maryland, the Americans, Israelis and Egyptians produced what Lawrence Wright describes in Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin, And Sadat at Camp David (Alfred A. Knopf) as “a partial and incomplete peace, an achievement that nonetheless stands as one of the great diplomatic triumphs of the twentieth century and one that has yet to be repeated.”

In signing what was effectively a separate peace with Egypt, Israel managed to neutralize its old enemy as a military foe, prompting Begin to later boast, “I have just signed the greatest document in Jewish history.” The Palestinians were the big losers. The autonomy Begin envisioned gave them little beyond local powers, keeping Israel fully in control of the occupied territories and enabling the Israeli government to build yet more settlements.

Wright, an American journalist who won the Pulitzer Prize for The Looming Tower, an analysis of the origins of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, has written a magisterial blow-by-blow account of Camp David. He examines the issues and provides pen portraits of the participants. It’s a model of lively and incisive journalism.

As Wright points out, Henry Kissinger, the former U.S. secretary of state, had warned Carter that no American president should embroil himself in Arab-Israeli negotiations where the outcome was in doubt. Hamilton Jordan, Carter’s former campaign manager, was also wary, warning Carter that he risked alienating the Jewish community if be brought pressure to bear on Israel.

“It was a paradox,” Wright observes. “Nothing could be a greater gift to Israel than peace, and nothing was more politically dangerous for an American politician than trying to achieve it.”

Carter’s goal had been to revive the Geneva Conference, which had met once in 1973 under the auspices of the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Nations. But after meeting Sadat at the White House, he thought he had found a leader capable of meeting Israel half way in peace talks. Carter knew little about Begin, except for Begin’s belief that the territories were “liberated” rather than “occupied.”

Wright suggests that Sadat would not have undertaken his historic trip to Jerusalem in November 1977 had it not been for Moshe Dayan’s secret meeting with Hassan el-Tohamy in Morocco the year before at the invitation of King Hassan II. Dayan, who had been minister of defence during the Six Day War, was now minister of foreign affairs in Begin’s new cabinet, while Tohamy, a former intelligence agent, was Sadat’s confidant.

“When Tohamy returned to Cairo, he evidently told Sadat that Begin had agreed to withdraw from the occupied territories. It was on this basis that Sadat went to Jerusalem, believing that only certain details remained to be worked out between the two sides,” says Wright. Dayan would deny he had led Tohamy to think that Israel was ready for a full withdrawal.

Working on this false assumption, Sadat told the Knesset that “a permanent peace based on justice” could only be achieved if Israel pulled out from the territories. Begin, in response, claimed, “No sir, we took no foreign land.”

Oddly enough, Sadat left Jerusalem convinced that he had scored an immense triumph and that the Middle East would never be the same after his initiative. He was disabused of this notion when Begin, shortly afterward, said that Egypt would regain sovereignty over the Sinai Peninsula, but that Israel would not give up its 13 settlements and two airfields in Sinai. As for the West Bank and Gaza, Israel would grant the Palestinians no more than limited autonomyand maintain its settlements and military presence.

Carter was enraged, saying that the settlements were illegal and that Begin’s autonomy scheme fell far short of the mark. Begin countered that Sadat’s trip to Jerusalem had been merely a grand gesture.

Despite their fundamental disagreements, Sadat and Begin went to the Camp David summit for their own good reasons. Apart from seeking the return of Sinai, Sadat hoped to build a better relationship with the United States after having ejected Soviet military personnel from Egypt. Begin did not want Israel to be perceived as unreasonable. “Carter had an engineer’s conviction that any problem can be solved if attacked with conviction, intelligence and persistence,” Wright writes.

Due to the yawning gaps between Israel and Egypt, the conference was in dire danger of breaking up more than once. In the first instance, Carter literally blocked Sadat’s and Begin’s path, begging for time so that he could devise a compromise.

By that juncture, Sadat was thoroughly disillusioned with Begin, not even being able to mention his name. Ezer Weizman, the Israeli defence minister, was the sole member of Israel’s delegation who developed a friendship with Sadat.

The acrimonious atmosphere at Camp David was such that one of Sadat’s key advisors urged him to go home rather than to submit to Israeli and American demands. Mohammed Kamel, the foreign minister, resigned even before the conference wrapped up, claiming that the real problem was not Begin’s intransigence or Washington’s pro-Israel policy, but Sadat’s infatuation with Carter’s vision of peace.

With the summit having come perilously close to breaking down over Begin’s hardline stance, Weizman implored Begin to relent. “There was going to be no way to disguise the fact that Israel had chosen to keep its settlements in Sinai rather than make peace with Egypt,” Wright says. “Dayan agreed that Israel could not afford to be the cause of the failure of the talks. It wasn’t just a question of peace with Egypt. Israel’s relationship with the U.S. was also at risk. Some concession had to be offered.”

The breakthrough occurred when Gen. Avraham Tamir, the Israeli military advisor at Camp David, approached Weizman with a plan to contact Ariel Sharon, the architect of Israel’s settlement program. If he could be convinced that a peace treaty with Egypt was more important than the Sinai settlements, perhaps he could influence Begin. This is precisely what happened after the Israeli delegation heatedly debated the proposition.

One may wonder why Sadat, his own objections notwithstanding, opted for a separate peace with Israel. Sadat, Wright explains, was certain that Carter would try to resolve the Palestinian problem in his second term of office. As well, Sadat was convinced that Egypt needed peace to mend its ailing economy.

In the wake of Camp David, Wright notes, Begin publicly disclaimed aspects of the agreement and complained about the pressure Carter had exerted on him. He made it clear that Israel would continue building settlements and that the Israeli army would remain in the West Bank and Gaza indefinitely.

Nevertheless, Israel and Egypt signed a peace treaty six months later. Despite a series of crises since 1979 — Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the eruption of the second Palestinian uprising in 2000 and the accession to power temporarily of a Muslim Brotherhood president in Egypt in 2012 — the treaty has endured.

In concluding, Wright claims that, of all three men, Carter was the only one who genuinely believed from the outset that an Israel-Egypt peace treaty was within reach. “Sadat was negotiating mainly to supplant Israel as America’s best friend in the region,” he writes. “Begin’s main goal was to avoid blame for failure.”

Carter persisted and gave Israel a wonderful geopolitical gift — peace, cold though it has been, with its most powerful Arab neighbor.