David Koffman asks a pointed question in the introductory essay of his book, No Better Home? Jews, Canada, and the Sense of Belonging (University of Toronto Press): “Has there ever been a better home for the Jews than Canada?”

As he observes in this volume of perceptive and erudite essays, which grew out of a symposium at York University in 2017, it’s a question that is seldom asked. “This is curious, because Canada may now very well be the safest, most socially welcoming, economically secure, and possibly most religiously tolerant home for the Jews than any other diaspora country, past or present.”

Koffman’s assertion is audacious. Have Jews really fared better in Canada than in the United States? And in light of an upsurge in antisemitic incidents in Canada following Israel’s most recent cross-border war with Hamas, would Koffman, a professor of Canadian Jewish studies at York University, still stand by his claim? I suspect so.

No Better Home? was published several months before the outbreak of hostilities in and around the Gaza Strip this past May. The antisemitism released by that conflict was a source of concern, of course, but it did not change the fundamentals of Jewish life in Canada, which is home to the world’s fourth largest Jewish community after Israel, the United States and France.

As Koffman argues, Jews in Canada are socially accepted, have access to economic opportunities unrestricted by their faith, enjoy the capacity to exercise political power unfettered by antisemitism, and are not subjected to violent forms of anti-Jewish animus. “These are powerful social markers of comfort and belonging for Canadian Jews,” he writes. “These yardsticks should be … appreciated.”

In his essay, Morton Weinfeld, a professor of sociology at McGill University, argues that minorities are treated “quite well” in Canada. And he reminds readers that Canada has no openly anti-immigrant, xenophobic or racist political parties with significant shares of the popular vote. But 14 percent of Canadians are antisemitic, and Islamophobia is a recurring phenomenon.

“Antisemitism has always been a major element of the Canadian Jewish experience,” he says. “Things began to change in the 1960s, when more space was created for Canadian Jews ….”

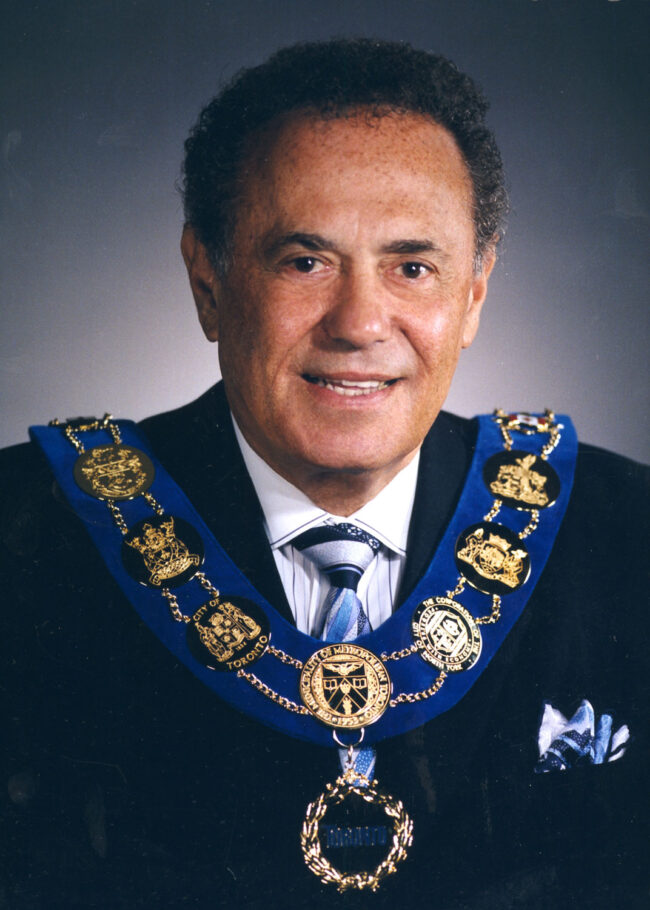

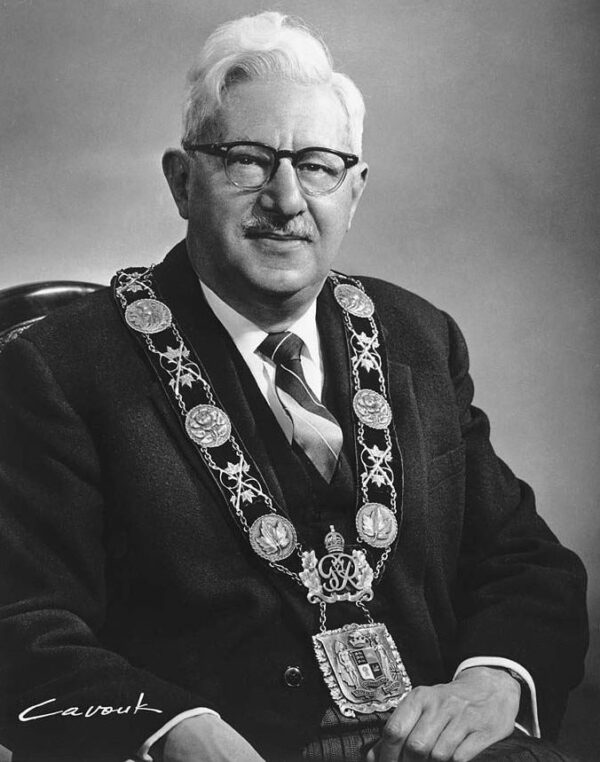

At the senior levels of political leadership, Jews have rarely reached the very top. David Lewis was leader of the New Democratic Party, but only one Jew, Dave Barrett in British Columbia, has been a provincial premier. Stuart Smith, Stephen Lewis and Larry Grossman were leaders of major parties in Ontario. There have been three Jewish majors of Toronto — Nathan Phillips, Phil Givens and Mel Lastman.

Hasia Diner, a professor of Jewish history at New York University, says that Canada has given Jewish immigrants wishing to improve their lives a fine home. “It provided them with untrammelled freedom to find work, make a living, build families and create … Jewish communities …” But she disagrees with the notion that Canada has been a better home for Jews than the United States.

Jeffrey Veidlinger, a professor of history and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan, offers an overview of multiculturalism in Canada. Ukrainian Canadians called for it as an alternative to English-French biculturalism, arguing that multiculturalism would reflect Canada’s demographic reality.

Major figures in the Jewish community initially opposed multiculturalism. Saul Hayes, the executive director of the Canadian Jewish Congress, contended that Canada is “a partnership of two founding races.” He was concerned that “a splintering of power would diffuse the ability of Jews to intercede and lobby with the government.”

Veidlinger adds, “If Canadian identity came to be regarded primarily in terms of ethnicity rather than religious faith, he feared, the Jews would become one of dozens of ethnicities, behind Poles, Ukrainians, Scandinavians, and a growing number off other immigrant groups.” Besides, Jews already had “preserved their cultural, linguistic and religious identities before the advent of multiculturalism.”

There are several essays about Montreal, which until quite recently was home to Canada’s largest Jewish community.

Kalman Weiser, a professor of Modern Jewish Studies at York University, writes that Montreal was a major center of Yiddish after World War II. Visiting the city in 1947, when the first wave of Holocaust survivors began arriving, the up-and-coming novelist Isaac Bashevis Singer compared it to pre-war Vilna.

Montreal and Vilna Jews were alike in that they desired to preserve their distinctiveness, Weiser says. Jews in Montreal tended to reside in “tightly grouped neighborhoods straddling the dividing line between the English and French parts …”

Since Singer’s visit, Yiddish has radically receded as a native language outside Hassidic circles. “If in 1931, 99 percent of Montreal Jews reported Yiddish as their mother tongue, by 1951 this number had declined to 54 percent,” Weiser writes.

Ira Robinson, a professor of Judaic Studies at Concordia University, examines the Montreal community since the Parti Quebecois’ victory in Quebec’s 1976 election. Since then, the anglophone population, which includes Jews, has declined by 90,000.

Many Jews were ill at ease with the province’s lurch toward separation from the rest of Canada. “Make no mistake, those bastards are out to kill us,” said Charles Bronfman, a wealthy businessman from a prominent Jewish family who threatened to leave Quebec. After the election, he was forced to issue a retraction, but his sentiments reflected widespread fears. Forty five years on, “a somewhat diminished and demographically different Montreal Jewish community maintains its place as the second largest Jewish community in Canada,” says Robinson.

Lois Dubin, a professor of religion at Smith College in the United States, describes Montreal Jews as “a kind of third solitude” in the city’s mosaic. A native of Montreal, she likens them to Habsburg Jews, who hewed to a tripartite identity. They were politically attached to the empire, culturally and linguistically German and ethnically Jewish. Like most Ashkenazic Jews, she considered herself politically Canadian and federalist, linguistically English and ethnically Jewish.

Yolande Cohen, a professor of French history at the University of Montreal, hails from Meknes, Morocco, where she felt she had no place. After a stint in Paris, she moved to Montreal in the 1970s. This is where she “found” herself. “I got married, raised two beautiful children, and pursued the career I dreamed of,” she says. “For me, there is no better place. I became a Quebecois and a Canadian, with a Moroccan Jewish origin. The possibility of keeping a multiplicity of belongings is perhaps the greatest factor that makes Canada a hospitable place for immigrants.”

Moroccan Jews fit snugly into Montreal, she believes. “As they spoke French at a time when French was becoming Quebec’s predominant language, it was quite clear … that Moroccan Jews diverged from Jewish immigrant patterns of integrating in the mainly anglophone group. Their determination to keep French as their main language and to establish themselves in the French culture became their main asset in a time when Quebec was asserting the predominance of French in its laws (Bill 101, for example).”

Ruth Panofsky, a professor of English at Ryerson University in Toronto, focuses on the approximately 40,000 Holocaust survivors who reached these shores after World War II. In particular, she offers an analysis of Bernice Eisenstein’s book, I Was A Child Of Holocaust Survivors, which was published in 2006. “A deeply personal account, it traces a daughter’s fixation on the Holocaust as she struggles to fathom its lasting effects on her parents and their survivor friends,” says Panofsky.

Eisenstein’s parents, Ben and Regina, were drawn most deeply to their close circle of fellow survivors, known as the Group. “It is only the Group, men and women who share a common past, that can provide her mother and father with a genuine sense of rootedness and connection — in essence, a feeling of home,” says Panofsky. “Neither the city of Toronto, which accepted them after the war, nor their own children, who are of their present and not their past lives, can offer the consolation they know with their friends.”

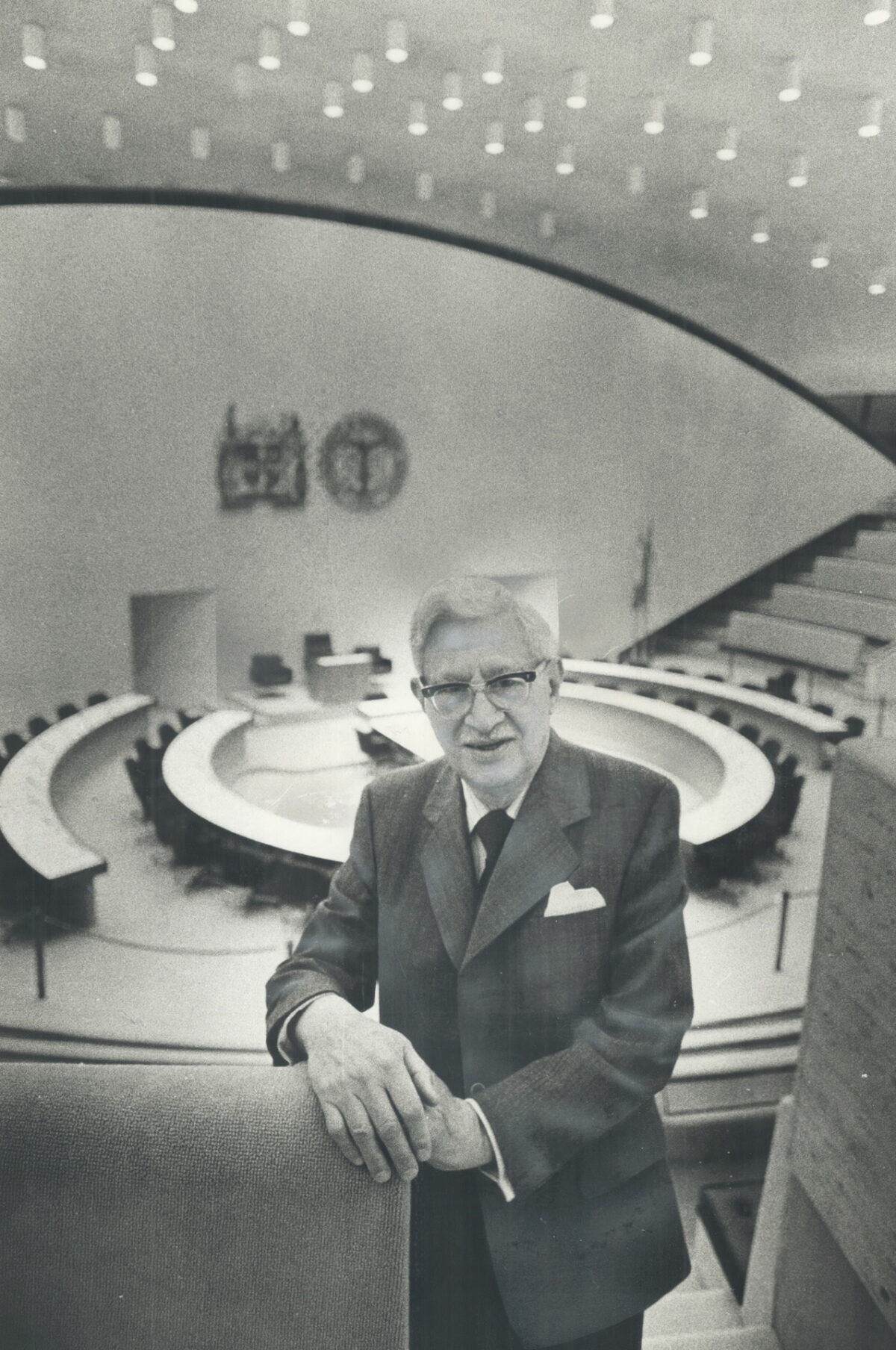

Harold Troper, a professor at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, writes about the election of Nathan Phillips in 1954 as the first Jewish mayor of Toronto. As he notes, Phillips’ triumph ended more than “a century-long history of Protestant mayors …. every one of them a member of the powerful Orange Order.”

The election took place at a moment when antisemitic restrictions were falling by the wayside. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that restrictive covenants barring Jews or other religious, ethnic and racial groups from purchasing property were illegal. With the opening of the new Mount Sinai Hospital, Jews wishing to study medicine at the University of Toronto were no longer bound by admission barriers.

Phillips, a lawyer by training, a member of the Conservative Party and a city councilman from 1926 to 1952, became a contender when the mayor, Allan Lamport resigned. With only a few months remaining before the next municipal election, Leslie Saunders was appointed as his successor. A member of the Orange Order, he was a bigot who had denounced Jews as slackers during World War II. The Toronto Star, a backer of the Liberal Party, supported Phillips’ candidacy, and he went on to win the next two elections by impressive margins.

Richard Menkis, a professor of history at the University of British Columbia, examines three museum exhibitions that broke the pattern of social and cultural Jewish marginalization in this country.

In 1945, when the amateur Jewish historian J.L. Levinson applied to the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada for recognition of Canada’s first synagogue, he was rejected. One of the board’s members admitted he was not “particularly interested in the commemoration of Jewish activities.”

Jews moved away from the margins in the 1970s, when the federal government funded Journey Into Our Heritage, an exhibit which concentrated exclusively on the western provinces from Manitoba to British Columbia. It was followed by A Coat of Many Colors in the 1980s, a nation-wide exhibition, and the Canadian Immigration Museum at Pier 21 in Halifax.

Judith Baskin, a professor of humanities emerita at the University of Oregon, relives her childhood in Hamilton. What shaped her, she says, was “the sense of otherness I absorbed as a Jew in an overwhelmingly Christian city and as the child of Americans in a provincial and insular Jewish community.”

She is the daughter of Reform Rabbi Bernard Baskin and his wife, Majorie Shatz, who arrived in Hamilton in 1949, little thinking they would remain there for the next half century and beyond. “My articulate and attractive parents passed well among gentiles, but the consciousness of being a Jew in a Christian world was always with us,” she writes. “And, certainly, the boundaries were always there.”

Toward the close of her essay, she says, “While antisemitism in various forms was well engrained in the history and attitudes of many sectors in the city, its forms were generally genteel. By the late 1960s Jews still were not members of tacitly restricted clubs and friendship circles … On the whole, Hamilton’s Jewish presence was too small to be perceived as a threat to the status quo. Rather, Jews were a benignly regarded and economically valued sub-group.”

Rebecca Margolis, who teaches courses in Jewish civilization at Monash University in Australia, surveys the status of Yiddish in Canada from the early 20th century to the present. With only three percent of Canadian Jews currently regarding Yiddish as their mother tongue, “the language now functions as a key to an immigrant or pre-Holocaust past, a facet of Jewish identity or other forms of personal identity.”

Outside of Hassidic communities, Yiddish is increasingly invoked rather than spoken. “Today, engagement with Yiddish within Canada’s mainstream is always voluntary,” she says.

Pierre Anctil is a rare bird. A professor of history at the University of Ottawa, he’s a French Canadian who has a special interest in Montreal’s Jewish culture.

He is convinced that francophone and anglophone researchers interested in Canadian Jewish history “have not really learned to work together… This dichotomy has produced a split that is closer to becoming unbridgeable, unless serious efforts are devoted to reducing the distance between the two camps. The consequences of this mutual alienation has been the emergence in recent years of two separate domains in the study of Canadian Jewish history, each with its own set of variables and perceptions.”

David Koffman, whom I’ve already mentioned, contributes an essay on the relationship between Jews and Indigenous people in Canada.

Jewish fur traders and merchants in the 18th century were the first Jews to establish contact with them. “Their interactions with First Nations involved a complex of economic, social, religious, political and even sexual relations, about which we know quite little,” he says. Koffman mentions such names as Ezekiel Solomons, Abraham Jacob Franks and Ferdinand Jacobs.

Jews also bought and sold Indigenous heritage objects, or curios, to tourists and museums. These items ranged from moccasins and belts to head-dresses and totem poles.

David Weinfeld, a visiting professor of religious studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, claims that Canadian Jews are so Jewish that they are more similar to American Jews than they are to Canadian gentiles. Nonetheless, Jews in Canada have succeeded in forming “a uniquely Canadian Jewish culture that distinguishes them from their American counterparts.”

He also claims that while Canadian Jews have “maximal political loyalty” to Canada, they are culturally closer to the United States.