For reasons that have yet to be explained, a Canadian government agency has rebuffed a request by B’nai Brith Canada and its supporters to release a list of suspected Nazi war criminals who were permitted to settle in Canada following World War II.

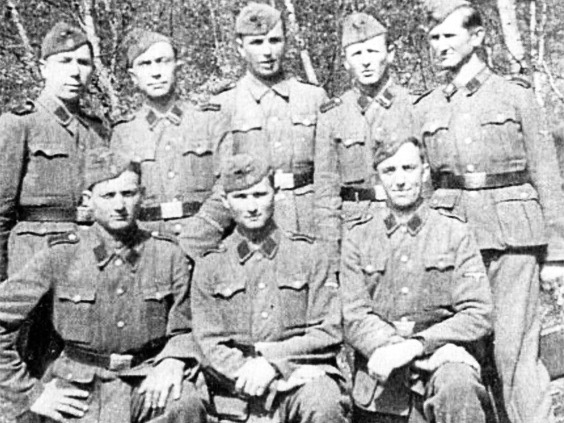

Among them were Germans who served in the German army and Ukrainians who joined the Galician SS division, which fought alongside the Wehrmacht and committed war crimes.

The data B’nai Brith has requested under the Access to Information law is contained in documents generated by the federal government’s war crimes commission, which was created in 1985 and headed by Justice Jules Deschenes.

For nearly four decades, Library and Archives Canada has declined to release the material to the public, a decision that is baffling and morally unacceptable.

As David Granovsky, B’nai Brith’s director of government relations, put it in a statement on December 19, “We must prevent history from repeating itself. It is imperative that everyone understands the degree to which this country was complicit in enabling Nazis to escape accountability for their crimes.”

B’nai Brith’s reasonable petition is supported by the Canadian Polish Congress, the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians, the Canadian Historical Association, the Montreal Holocaust Museum, 39 academics, and a number of former government officials.

If the past is any precedent, Library and Archives Canada may be amenable to changing its position if sufficient pressure is brought to bear.

Last February, it released all but one page and a few redactions of the 600-page Rodal Report, which was written by the Canadian historian Alti Rodal at the behest of the Deschenes commission.

The Rodal Report was declassified after the Yaroslav Hunka scandal in 2023. A veteran of the Galicia division, Hunka was honored in the House of Commons during a visit to Canada by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

After Hunka’s wartime record came to light, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized, while Immigration Minister Marc Miller conceded that Canada’s record regarding Nazi war criminals is dismal, and that he would consider requests to release more classified information about them.

Judging by the Rodal Report, 29 war criminals slipped into Canada. One of the culprits, an ethnic German named Helmut Oberlander, served in an Einsatzgruppen unit, or mobile killing squad, that massacred Jews in the Soviet Union. He arrived in Canada in 1954 and died in 2021 after fighting a deportation order.

Incredibly enough, criminals like Oberlander had an easier time getting into Canada than Holocaust survivors.

From 1945 until 1950, the federal government barred the entry of Nazi war criminals into Canada. But after a special panel of senior bureaucrats determined that communists were the most dangerous security threat facing Canada, the government opened the gates to these criminals, even as Jews encountered difficulties applying for Canadian visas.

Under Canada’s new regulations, Europeans with blood on their hands — war criminals such as Helmut Rauca and Jacob Loitjens — were allowed into Canada. Clearly, the Canadian government preferred northern and Central Europeans to Jewish immigrants.

Canada besmirched its image by knowingly letting in Nazi war criminals. Library and Archives Canada can make some amends by acceding to B’nai Brith’s request to release their names.

Canadians have a right to know the names of the war criminals granted sanctuary and citizenship in this country.

This information should not be concealed any longer.