How did Canada respond, publicly and institutionally, to the rise of Nazism in Germany? Part of the answer is found in Nazi Germany, Canadian Responses: Confronting Antisemitism in the Shadow of War (McGill-Queen’s University Press). A book of essays by Canadian academics, it explores a number of overlapping issues — Canada’s reaction to Nazism, Canada’s attitude to the plight of European Jewish refuges seeking to settle here and the nature of anti-Jewish discrimination in Canada.

It’s published about 30 years after the appearance of None Is Too Many, the classic by Harold Troper and Irving Abella on Canada’s restrictive immigration policy before and during World War II.

An essay on the campaign by the Canadian Jewish Congress to dissuade Canada from participating in the 1936 Olympic Games in Germany is written by Troper and Richard Menkis. “A Canadian boycott might not derail the Olympics, but Canadian Jews hoped it would convince the Nazis that the world was watching and there would be a price to pay for their continuing abuse of German Jews,” they write.

The Canadian Olympic Committee, following the lead of Britain, decided to attend the Olympic Games. Perhaps, as the authors suggest, the COC was influenced by Canadian media coverage of Germany. As they put it, “The mainstream Canadian press may have been politically partisan, but it was rarely monochromatic and never painted Hitler and the Nazis either entirely white or black.”

In her piece, Amanda Grzyb deals with with how newspapers covered Kristallnacht in 1938 and the St. Louis incident in 1939. There was extensive coverage of the Night of Broken Glass, the nation-wide pogrom in Germany, but reportage of Nazi antisemitism steadily declined after that.

She makes a telling point: “The English Canadian press was relatively unified in its condemnation of Nazi violence against the Jews and many Canadians took a stand to oppose Jewish persecution. But the country was far from united. Antisemitism continued to proliferate in Canadian culture, particularly in Quebec.”

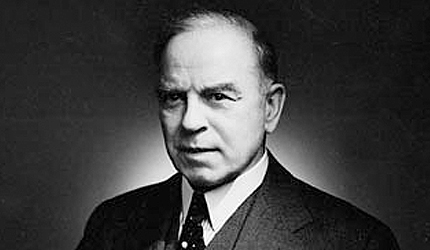

While the United States and Britain denounced Kristallnacht, she notes, Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King was conspicuously silent.

During the summer of 1939, she says, Canadian newspapers paid more attention to homegrown antisemitism. The Globe and Mail, for example, ran a front-page story on the prevalence of antisemitism in the Laurentian mountains town of Ste.Agathe-des Monts, where Jews were turned away from resorts and hotels.

Rebecca Margolis, in an essay on the Yiddish press, points out that it remains “a vital yet virtually untapped source on the Canadian Jewish experience in the first half of the 20th century, especially during the pivotal years of the Holocaust.”

In discussing the role of publications such as Montreal’s Jewish Daily Eagle and Toronto’s Daily Hebrew Journal, she says that they carried news stories of the fate of Europe’s Jews that general dailies ignored.

Michael Brown, in an essay on Canadian universities, reminds readers that Jewish students were subjected to quotas and that Jewish scholars found it almost impossible to obtain teaching positions. Such was that atmosphere in the 1930s that the dean of McGill University’s faculty of arts and sciences, Ira MacKay, could denigrate Jews with impunity.

In a reference to the feasibility of hiring German Jewish scholars, he wrote, “The Jewish people are of no use to us in this country. Almost all of them adopt merchandising, money lending, medicine and law, and we have already far too many of our own people engaged in these occupations. As a race of men, Jews do not fit in with a high civilization.”

MacKay, Brown writes, was instrumental in introducing the Jewish quota system to McGill by requiring Jewish applicants to score 75 out of 100 on their high school matriculation exams, compared to 60 out of 100 for gentiles

As Brown adds, university campuses were not only redoubts of reactionary opinion. During the St. Louis incident in 1939, a petition sent to Prime Minister Mackenzie by some leading academics, including the historian George Wrong of the University of Toronto, urged him to ease Canada’s discriminatory immigration policy.

James Walker, in an essay on the Jewish struggle for inclusion in Canadian society, points out that French Canadian priest and historian Lionel Groulx was a leading contributor to the journal L’Action Nationale, whose writers were in favor of depriving Jews of civil and political rights.

This was an era when explicit antisemitism was in the air and taken for granted, Walker suggests.

The Social Credit Party, which attained power in Alberta in 1935, promoted the doctrine that an international Jewish conspiracy sought to dominate the world. Maurice Duplessis, the premier of Quebec, exploited antisemitism for political purposes. Samuel Bronfman, the president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, was forced to form a special committee to counter innuendos that able-bodied Jewish men were shirking military service during the war.

Walker also touches on the issue of restrictive property covenants, which kept Jews out of certain neighborhoods. These covenants were declared illegal in Ontario in 1945, paving the way for a more democratic, pluralistic and inclusive Canada.

The essayists in this useful book, edited by Ruth Klein, raise these points with rigor and clarity.