Muslims are the fastest growing religious minority in Canada. The arrival of 40,000 Syrian refugees in the past year certainly accentuated this trend. From 600 Muslims in Canada in 1931 to 579,000 in 2001 and to more than one million in 2011, the size of the Muslim community has grown exponentially.

Statistics Canada expects the Muslim population to double to 2.5 million within the next 20 years, by which time seven percent of Canadians will be Muslims. Muslim immigration to Canada has come mainly from Pakistan, Iran, Algeria, Morocco, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and India.

Jews have been in Canada much longer than Muslims, but at last count, Canada was home to about 375,000 Canadians of the Jewish faith, or 1.1 percent of its population.

The emergence of a numerically significant Muslim presence in Canada has not been without difficulties. Compared to the pre-World War II period, Canada is a tolerant, multicultural nation that welcomes new immigrants. Indeed, the federal government recently announced a plan to increase immigration. Nonetheless, as a comprehensive report issued by the Environics Institute in 2016 indicates, Muslims here do not “enjoy the acceptance of other religious minorities.” Indeed, uncomfortable questions have been raised in some quarters about their suitability as Canadians.

In general, Muslims in Western countries have been regarded problematically since the events of September 11, 2001, when 19 Muslim Arab terrorists crashed commercial passenger planes into the World Trade Center in New York City, the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. and a field in rural Pennsylvania.

Since then, the vast majority of terrorist acts around the world have been perpetrated by ideologically driven jihadists under the sway of radical Islam. Yesterday, salafists killed more than 200 Egyptians in a mosque in the Sinai Peninsula. Add to that the fact that several imams have been caught preaching hatred against Jews, and that a disturbing number of young Canadian Muslims have joined the ranks of Islamic State, an organization that encourages intolerance toward non-Muslims.

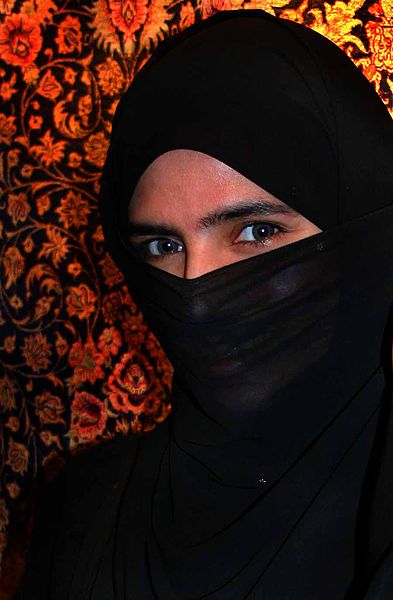

The sartorial practices of Muslims have been a source of controversy as well.

As the Environics Institute study points out, head coverings worn by Muslim women have been a flash point in Western countries such as France and Belgium, which have both banned face coverings in public. The issue in Canada surfaced when a woman was barred from a Canadian citizenship ceremony unless she uncovered her face during the oath of allegiance. She took her case to court and won, but the issue morphed into a political football during the last federal election.

It has since burst wide open in the province of Quebec with the passage of Bill 62, which requires people to uncover their faces to receive public services. Quebec’s justice minister, Stephanie Vallee, who shepherded the legislation through the National Assembly, justifies the bill on the grounds of communication, identification and security. Bill 62, she says, represents a “well balanced response” to a debate over reasonable accommodation toward minorities that has been going on in the province for about the past decade.

Earlier this month, civil liberties advocates and a convert to Islam who wears a niqab, Warda Nailli, challenged the legality of Bill 62, filing a motion against it in Quebec’s Superior Court. The plaintiffs maintain that it contravenes Quebec’s Charter of Human Rights and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. “Such blatant and unjustified violations of freedom of religion … have no place in Quebec or Canada,” they said in their court filing. “These violations cannot be justified in Quebec’s free and democratic society.”

The premiere of Quebec, Philippe Couillard, disagrees with these assertions, saying that Bill 62 was crafted to be in compliance with the Canadian and provincial charters.

According to the Environics Institute, the practice of wearing head coverings is widespread and growing in Canada. Fifty three percent of Muslim women surveyed say they wear a hijab, chador or niqab in public, compared to 42 percent in 2006. Forty eight percent wear the hijab, up 10 points in the last 10 years. Three percent wear the chador, unchanged since 2006, while three percent don the niqab.

The institute adds that the practice of using head coverings has grown most noticeably among Muslim women from the ages of 18 to 34. “Head coverings in public continue to be most widely reported by women with no more than a high school education, but this practice has seen the most growth in the past decade among those with a college or university education. Women who visit mosques at least once a week are much more likely to wear a hijab (72 percent) than those who rarely do (34 percent), but the practice has increased more noticeably among this latter group. Moreover, it is women who rarely or never visit mosques for prayer who make up the majority who wear a chador or niqab.”

Interestingly enough, this issue divides Muslims in Canada.

Sixty percent believe Muslim women should have the right to participate in citizenship ceremonies while wearing a niqab, but 24 percent disagree. The remainder say it depends on the circumstances, or offer no opinion.

Among non-Muslim Canadians, 45 percent oppose the niqab at citizenship ceremonies, while one-third oppose the right to wear the niqab while receiving public services. In both cases, opposition is most evident among Quebecers, Catholics, older Canadians and those with less education.

The niqab will probably be an issue in the future.

As the institute suggests, “Muslims are one of the most religiously observant groups in Canada, and their religious identity and practices appear to be strengthening rather than weakening as their lives evolve in Canada. And moving to Canada does not appear to be having a secularizing effect: Immigrants are more likely to say their attachment to Islam has grown rather than waned since arriving in the country.”