I first saw Chariots of Fire, the award-winning British movie, at the 1981 Toronto International Film Festival. Having been moved by it, I jumped at the chance of watching it again, this time on the Turner Classic Movies channel.

As I tuned in, I wondered whether it would have the same mesmerizing effect on me.

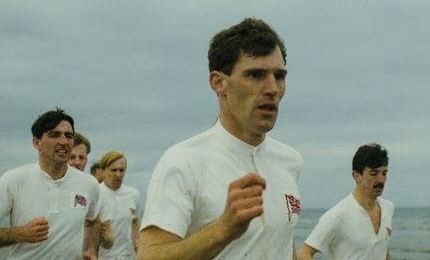

Directed by Hugh Hudson, who died earlier this month, it focuses on two legendary British athletes — Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell — who won gold medals at the 1924 summer Olympic Games in Paris.

They could not have been more different in terms of their backgrounds. Abrahams was Jewish, the scion of a Lithuanian immigrant family. Liddell, a Scotsman, was a pious Christian from a missionary family that worked in China.

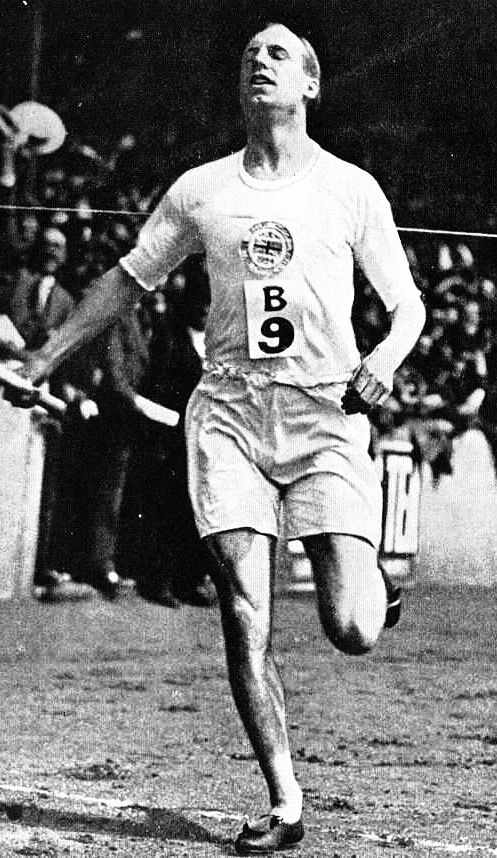

Abrahams was a gold medallist in the 100 meters race, the first and still only Jewish sprinter to have achieved stardom in that glittering event. Liddell sprinted to victory in the arduous 400 meters race. Both men were awarded silver medals in the 400 meters relay.

Chariots of Fire, which concentrates on the first two events and ignores the third, opens as Abrahams (Ben Cross) checks into a dormitory at Cambridge University, where he will study law.

Casual antisemitism is in the air.

The nasty clerk who signs him in mutters, “With a name like Abrahams, he won’t be in the chapel choir.”

Shortly after Abrahams breaks a centuries-old track-and-field record at Cambridge, a wizened university administrator, played by the inimitable Sir John Gielgud, comments acidly, “They are god’s chosen people.”

Confiding in a friend, Abrahams glumly compares himself to an “alien.”

Speaking to his glamorous girlfriend, Sybil (Alice Krige), Abrahams likens running to “a weapon against being Jewish.” Claiming to be “semi-deprived” as a Jew, he says, “They lead me to water but won’t let me drink.”

Nonetheless, Abrahams, an assimilationist, considers himself “an Englishman first and last.” And he exudes remarkable self-confidence. “I’m going to take them on one by one and run them off their feet,” he boasts. His ambition is to win a medal at the forthcoming Olympics, a feat that eluded him at the 1920 Olympic Games in Amsterdam.

Liddell (Ian Charleson), whom one of his admirers describes as a “muscular Christian,” has no problem fitting in. All he has to do is to “run in god’s name and let the world stand back in wonder.”

Abrahams recognizes that Liddell, a University of Edinburgh student, may be a serious rival after watching him win a race. Realizing there is room for self-improvement, he considers the possibility of hiring a professional coach.

In his first race against Liddell, Abrahams finishes second. He’s crushed by his defeat, but Sam Mussabini (Ian Holm), a seasoned coach of Arab, French and Italian descent, thinks he has the ability to run still faster.

Abrahams’ association with Mussabini elicits the disapproval of university administrators, who fervently believe that amateur athletes should not be coached by professionals. They criticize Abrahams, but do not take the matter any further. As one of them commented earlier in the film, “They say he can run like the wind.”

In the meantime, Liddell’s overtly pious girlfriend urges him to quit the sport and devote body and soul to the ministry. He intends to hang up his cleats, but not before he runs at the Olympics. Justifying his decision, he says, “To win is to honor him (god).”

A significant proportion of the film unfolds at the Olympics. Much to the surprise and disappointment of the British Olympic Committee, Liddell announces he cannot run in the 100 meters race because it falls on a Sunday, the sabbath. The Prince of Wales, the heir to the British throne and a member of the committee, asks him gently whether he can bend this rule, but Liddell is adamant. He is a man of principle.

A solution is found, and Liddell competes instead in the 400 meters event, which is scheduled for a mid-week day.

Disappointingly, the separate races in which Abrahams and Liddell participate are almost anti-climactic. Strangely enough, they are bereft of the nail-biting tension that impressed me more than 40 years ago. My reaction may be directly related to the fact that I originally watched Chariots of Fire on a big screen rather than on television.

Be that as it may, it is a fine film, having won four Academy Awards, including the best picture prize. The actors who portray the main characters are convincing, and Vangellis’ musical score, which kicks in at the beginning and the end, is uplifting and inspirational.

While Chariots of Fire is hardly a masterpiece, it crackles with passion and excitement and delves into an issue, antisemitism in polite British society, that can hardly be ignored.