Call it, if you like, a fantastic fluke.

The 2,000-year-old Army of Terracotta Warriors, one of the most astonishing finds of the 20th century, might never have been excavated had it not been for a natural disaster that ravaged the central Chinese province of Shaanxi in 1974.

The chain of events that culminated with this discovery started in the village of Xi Yang, 35 kilometers east of Xian, when farmers beset by a drought began digging a well. To their astonishment, they stumbled upon a vault of earth, brick and timber that yielded a surrealistic trove of thousands of life-size terracotta soldiers, horses and chariots.

Being superstitious, the peasants assumed that the weathered clay soldiers, armed with real weapons, were evil spirits. Out of fear, they smashed one of the figures.

An amateur archeological who examined the vault was so thunder-struck that he took fragments to a local museum. This, in turn, prompted the Chinese government to establish a museum in the city of Xian that houses this fabulous treasure today.

Xian and its outlying areas are not only known for these unique clay soldiers. A world-class city during antiquity that vied with Rome and Constantinople for prominence, Xian has the distinction of being China’s only major metropolis ringed by an ancient wall.

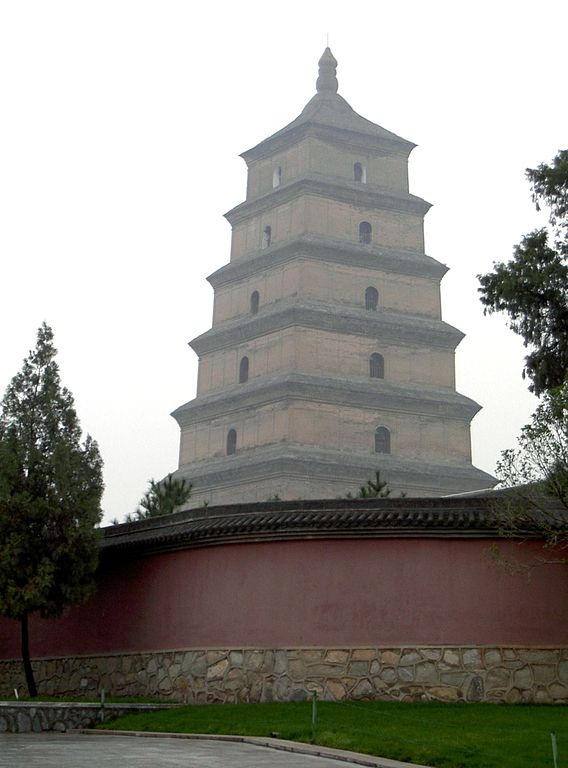

In addition to its seventh century Big Goose pagoda, Xian has two excellent museums — the Tang Dynasty Art Museum and the Shaanxi History Museum — and an atmospheric Muslim quarter.

As worthy as these attractions may be, they pale in comparison to the Army of Terracotta Warriors, the legacy of Qin Shihuang, the emperor who unified China more than 2,000 years ago.

Before he died, Qin ordered the construction of his own tomb, which was to be guarded by thousands of clay soldiers. The mausoleum, 1.5 kilometers from the vaults where the clay soldiers were buried, was built by 700,000 workers over a 38-year period.

The purplish-colored terracotta infantrymen and cavalrymen, who guarded the emperor after his final journey into supposed immortality, were not in the best physical condition during my visit. Originally placed in upright positions, they were toppled by earthquakes, floods and erosion. The vaults were also damaged by fires during a peasants’ revolt, according to a short film visitors may watch.

In the quest of authenticity, the museum has allowed some of the warriors to remain scattered in pieces, exactly as they were found. Other soldiers have been put back together again, while still others will be coated with special chemical preservatives before they’re exhibited.

The vaults, which resemble giant pitted sand boxes, contain armies of eerie-looking soldiers in battle-ready formations. A few of these fearsome warriors, including a kneeling archer, a stolid cavalryman and a general clad in a long robe, are displayed in bullet-proof glass cases. Still other cases exhibit their weapons: crossbows, swords, scimitars, spears, daggers, axes, lances and knives.

The overall effect is mesmerizing.

Xian, with a population exceeding six million, is a historic city with classical Chinese buildings where the celebrated Silk Road — the trade route linking China with the Mediterranean Sea — began.

Its blackened wall, 14 kilometers in circumference and 12 meters high, encloses Xian’s downtown core. Built on the foundations of the Tang dynasty’s Forbidden City, the wall hosts the modest but intriguing Chinese Calligraphy Museum, which charts the development of Chinese script from the Northern Song dynasty to the Ming and Qing dynasties.

The far larger Tang Dynasty Art Museum features mannequins of Chinese imperial figures, reproductions of Tang tomb paintings and Silk Road figurines influenced by Persian art.

The Shaanxi History Museum, which opened in 1992, is an unimaginably rich repository of priceless artifacts. Upon entering the museum, a visitor comes face to face with a massive stone lion, the biggest in China. It was taken from the tomb of the mother of Empress Wu, China’s first and only female ruler. Also of interest are skull fossils, primitive tools from China’s earliest history, currency, writing paper, burial objects and a procession of 300 one-foot funerary guards.

The Big Goose Pagoda, set on immaculately manicured grounds, is a marvel of Ming architecture, as is the Bell Tower, a symbol of Xian.

Xian’s Muslim quarter, several minutes by foot from the Bell Tower, hums with vitality. Muslim men sporting white caps and Muslim women wearing scarves tend to smoky braziers browning skewers of fish and meat.

Vendors of fruits, vegetables and nuts wait for customers. Bakeries churn out aromatic pitas. Diners sit on low stools and wolf down noodle dishes. Souvenir hawkers peddle trinkets, jewellery, posters, paintings and jade.

The Great Mosque, uniquely, is shaped like a pagoda, the only one of its kind in the world. Its ensemble of sedate buildings date back to the 18th century and earlier and sprawl over four courtyards covering an area of 13,000 square meters.

Xian’s center, with its crowded sidewalks and modern malls, pulsates with frenetic energy. At night, the glow of neon illuminates the city garishly.

Xian, of course, is a shopper’s mecca. The silk carpets in the HauHui Folk Craft Center are exquisite and the lacquer furniture and decorative wooden boxes in the Xian W.B.Z. Tourism Shopping Center are beautiful beyond belief.

After much hesitation, I bought a lovely wooden cabinet in shades of maroon, gold and pale green, and to this day it’s one of the finest acquisitions I’ve ever acquired.