With the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation in Germany approaching, German eyes will be fixed on its leading light, the theologian Martin Luther, who was born in 1483 and died in 1546. Luther was a Christian rebel who, in 1517, questioned papal authority and thereby touched off a revolution in Christianity.

As revered as he may be among Lutherans, Luther was a vicious antisemite whose anti-Jewish writings contributed to the dissemination and entrenchment of antisemitism in Germany and other countries. For hundreds of years, Lutherans have quietly tolerated, if not promoted, his warped view of Jews and Judaism. Luther’s antisemitism was celebrated particularly during the Nazi era.

But now, in a major development, the Evangelical church in Germany has made a dramatic U-turn, which bodes well for Lutheranism’s soul and Christian-Jewish relations.

Last month, in response to a plea from Josef Schuster — the head of the Central Council of Jews in Germany — the church’s decision-making body, the Synod, unanimously distanced itself from Luther’s anti-Jewish rhetoric and promised to confront its dark past.

With its jubilee less than a year away, the church issued a belated historic statement that is surely bound to clear the air. Expressing “sorrow and shame” for its failure to respect Jews, the church acknowledged it has a special responsibility to combat all forms of antisemitism.

“Luther’s view of Judaism and his invective against Jews contradicts our understanding today of what it means to believe in one God who has revealed himself in Jesus, the Jew,” the statement added. “We cannot ignore this history of guilt.”

Luther’s animus toward Jews was so deep and venomous that it is sometimes forgotten that his path to antisemitism was circuitous.

During his early phase, he was not the horrendous bigot he would become. In an essay, That Jesus Christ Was Born A Jew, he condemned the inhumane treatment of Jews and called upon Christians to treat them decently. In a reference to Christian mistreatment of Jews, he wrote, “If I had been a Jew and had seen such dolts and blockheads govern and teach the Christian faith, I would sooner have become a hog than a Christian.”

In another essay, Servitude of the Jews, he wrote: “What Jew would consent to enter our ranks when he sees the cruelty and enmity we wreak upon them — that in our behavior towards them we less resemble Christians than beasts?”

He was animated by an ulterior motive, hoping that Jews would see the error of their ways and convert to Christianity.

Luther promised Jews they would be received with kindness by Christians if they followed the path of conversion. As he put it, “Yes, we will show them Christian love and pray for them that they may be converted to receive the Lord, whom they should honor properly before us.”

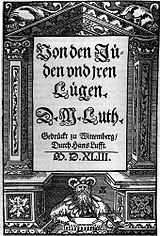

Having been unsuccessful in persuading Jews to convert en masse, he turned against them with cold fury. In 1534, he published On The Jews And Their Lies, in which he described Jews as a “rejected, base, whoring and condemned people” and recommended that harsh measures be taken against them.

Their synagogues and schools should be set on fire. Their houses should be razed and destroyed. Their blasphemous prayer books, silver and gold should be taken away from them. They should be expelled from the country.

This is what he said.

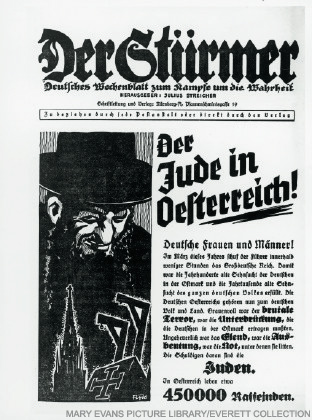

Luther’s fulminations reinforced the foundations of Christian antisemitism in Germany and throughout Europe in the centuries to come. After his death, Jews were expelled from some German states. The Nazis trotted out his diatribes to justify their antisemitic policies. In keeping with the times, the city of Nuremberg presented a first edition of On The Jews And Their Lies to Julius Streicher, the publisher and editor of Der Sturmer, an obscenely antisemitic newspaper.

Luther left behind a deadly and disgraceful legacy that was expropriated by the church and exploited by professional racists. It now falls on the Evangelical church to discredit and erase this hateful legacy from its gospel.