The creation of Israel in 1948 was a joyous event in Jewish history, but a catastrophe for Palestinian Arabs. Six Arab armies invaded the new Jewish state after David Ben-Gurion’s declaration of independence, while Palestinian fighters continued their guerrilla war against Israel. During the fighting, eight out of 10 Palestinians fled or were driven out, leaving about 160,000 of their compatriots in Israel.

Comprising 15 percent of Israel’s total population, the Palestinian Arabs were seen as a potential threat by some Israelis. Nevertheless, the Israeli government granted them suffrage rights and citizenship. For the first two decades of its existence, however, Israel restricted their movements, civil rights and employment opportunities.

This, broadly, is the subject of Shira Robinson’s book, Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State, published by Stanford University Press.

Robinson, an associate professor of history and international affairs at George Washington University and an Israeli by birth, examines these issues from a critical left-wing point of view.

She refers to the Zionist movement as the “collective settler project.” She claims that Israel’s aim was “to alienate indigenous Palestinians from their land while keeping them economically dependent and politically divided.” She points out that “the Zionist project in Palestine was the only 20th century settler movement to attain majority status and internationally recognized statehood.”

Robinson starts with a brief survey of Jewish settlement in Palestine, which began in the modern era in 1882, when 24,000 Jews were already living there alongside 500,000 Muslim and Christian Arabs. Britain, the colonial power in Palestine after World War I, struggled to reconcile its promise to grant the Arabs self-rule with its pledge to create a Jewish national home in Palestine.

In an attempt to cultivate allies among Palestine’s religious and ethnic minorities, the Zionists reached out to Circassian Muslims, Maronite Christians, Druze, Ahmadi Muslims and Persian Baha’is. Their efforts bore fruit, facilitating secret land purchases, among other objectives. By 1918, Jews had bought almost six percent of the land in Palestine, a figure that would not rise appreciably in the next 30 years.

As she suggests, the United Nations Palestine partition plan, passed on Nov. 29, 1947, was rife with promise and peril.

On the one hand, it was a triumph of Zionist diplomacy, giving Jews 51 percent of the territory and lending international legitimacy to Jewish statehood.

On the other hand, the plan was a demographic nightmare insofar as Zionists were concerned. If the Palestinians had accepted the UN resolution, nearly half of the future Jewish state’s population would have consisted of Arabs.

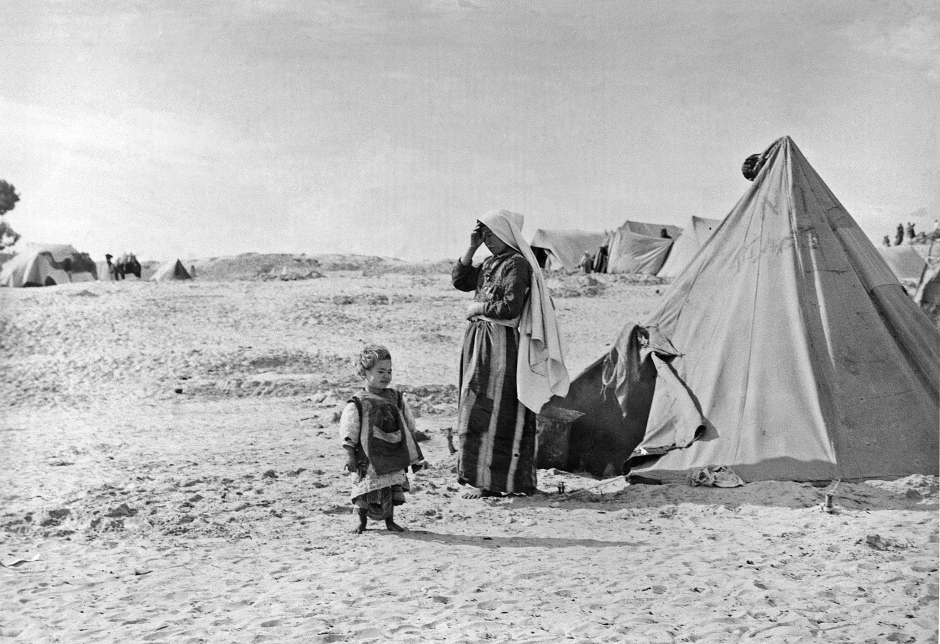

By the end of the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948, Jewish forces had conquered 78 percent of Palestine and 750,000 Arabs had left the country voluntarily or under duress, leaving behind about 425 villages and 11 cities in which they had lived.

Transjordan, meanwhile, occupied the West Bank, while Egypt seized the Gaza Strip.

“What remained of the Palestinian people inside (Israel) was a poorer, more rural, less educated and largely leaderless shadow of its former self,” observes Robinson.

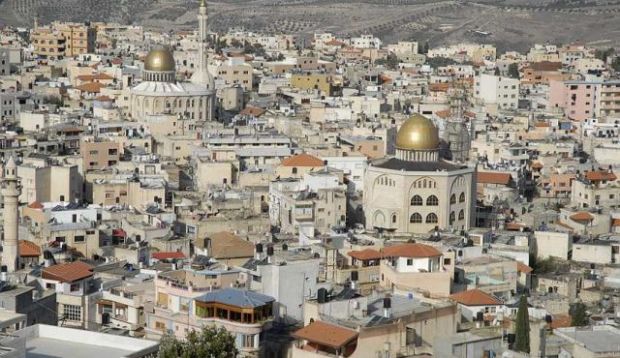

After 1948, Palestinians inhabited 100 villages, the town of Nazareth and neighborhoods in five Israeli cities: Haifa, Ramla, Lod, Acre and Jaffa. Few of the villages had electricity, running water or sewage systems, and medical care was a problem, too. Until 1954, she notes, the Israeli government did not assign a single state doctor to the villages of the western Galilee.

Israel’s greatest fear after statehood was that Palestinian refugees would try to return to their homes and properties, perhaps with global support. Indeed, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution calling on Israel to repatriate refugees willing to live in peace with Jews. The resolution was never implemented and, in the meantime, Israel launched a concerted campaign to squelch the Palestinians’ right to return.

Using emergency regulations promulgated in 1949, Israel established military rule in the Arab sector, or closed residential zones that Israeli Arabs could not leave without a permit. “In the Galilee and the Little Triangle (the border area closest to the West Bank), where the overwhelming majority of Palestinians in Israel lived, virtually every aspect of daily life required a military pass,” she writes.

Permits were extremely difficult to obtain, and in the Little Triangle town of Umm al-Fahm, the largest in the area, only 13 percent of its 6,000 residents possessed them.

Several Israeli cabinet ministers opposed military rule over the Arab minority, but almost two decades would elapse before it would be officially abolished.

The curfew, an integral part of this system, was the cause of a humanitarian disaster on the eve of the 1956 Sinai war. When some of the inhabitants of the village of Kfar Kassem inadvertently broke the curfew, they were summarily shot in cold blood by Israeli border guards.

Robinson also deals with the land question, which lies at the heart of Israel’s struggle with the Palestinians. In the aftermath of the 1948 war, Israel confiscated Arab lands on a mass scale, building 350 of 370 new settlements on them. Even today, this issue is a source of disaffection in the Israeli Arab community.

Israel did not treat all Arabs cavalierly. The Druze, an Arabic-speaking sect who sided with the Jews during the war, were given preferential treatment in the wake of the war. They were neither expelled from their villages nor subjected to restrictions.

Concerned by reports that the Arabs were chafing under military rule, the government agreed to phase it out gradually. Protests by hundreds of Jewish academics, artists and settlement leaders, plus opposition from the security establishment, finally convinced Israel that it should be eliminated altogether. This, belatedly, happened in 1966, by which time Israeli Arabs were no longer regarded as an existential threat.

Robinson has written an interesting and rigorous account of Israel’s often contentious relationship with its Arab minority in the first 20 years of statehood. Some of her observations are spot on, but in general, her book is marred by a lack of balance. Being resolutely pro-Palestinian, she has little or no sympathy or empathy for the Israeli side. You can take what you wish out of Citizen Strangers, and there is plenty to chew on, but be mindful of its overt political slant.