A lush, palm-fringed island in the southern Indian state of Kerala, Fort Cochin is a cosmopolitan blend of cultures and an oasis of calm. Inhabited by Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Jews, it’s a mirror image of India’s rainbow of ethnic and religious groups.

Part of greater Cochin, or Kochi, Fort Cochin faces the Arabian Sea and has one of the world’s finest natural harbours. Once an obscure fishing village, it’s now an international destination, attracting both well-heeled tourists and backpackers.

Strongly influenced by Portuguese, Dutch and British settlers, Fort Cochin seems far from the hustle, bustle, noise and pollution of Indian cities like Mumbai or New Delhi. Indeed, it revels in its languid pace.

Men in sarongs, pedalling bicycles on tree-lined lanes trilling with birdsong, glide past low-slung residences garlanded in bright shades of bougainvillea and set behind bamboo fences and palm trees. Women walk children to school, passing the occasional elephant guided along by a driver and a handler.

Linked to the fabled Malabar Coast by ferry and bridges, Fort Cochin is known for its distinctive buildings.

St. Francis Church, built by the Portuguese colonialists in 1503 and renovated by the Dutch in 1779, is architecturally striking, distinguished by a beige facade, arched brown windows and a bell tower. The remains of Vasco da Gama, the Portuguese explorer, lay inside St. Francis, the first church in India, for 14 years before being sent to Portugal.

The nearby Dutch cemetery, consecrated in 1724, contains a sea of weathered and crumbling tombstones. Huge tropical hardwood trees, originally imported from Brazil, loom over its walls.

Jewtown, a quaint neighbourhood of private homes and handicraft and spice shops, is dominated by the Pardesi Synagogue, the oldest shul in India. Finished in 1568, destroyed by the Portuguese and rebuilt almost a century later during the Dutch era, the white-walled synagogue reflects the long Jewish presence in India.

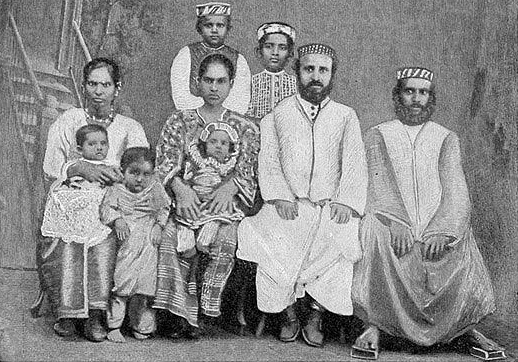

Jewish traders from the Land of Israel arrived during the biblical period, and further waves of Jews came after the Spanish Inquisition. Populated by more than 2,000 Jews several generations ago, Fort Cochin’s Jewish community has dwindled drastically in recent years. As I sat on a teakwood bench in the synagogue, a caretaker told Sikh visitors that the Jewish community would disappear one day soon. He’s probably right.

The interior of the synagogue is exquisite. Its pale blue walls, European chandeliers, hand-painted Chinese blue floor tiles, Indian oil lamps and Torah scrolls leave a remarkable impression.

Jewtown brims with intriguing handicraft shops specializing in delicate Mogul art and masterfully-crafted woodwork. Being partial toward such objets d’art, I spent almost two hours rummaging through the wares at these emporiums.

Jewtown’s spice stores, which recall Cochin’s ancient trade with King Solomon, are filled with burlap bags containing a wide range of condiments from cloves, nutmeg and cinnamon to black pepper, coriander and star anise. The aromas are intoxicating.

As I wandered through Jewtown, I came upon Sarah Cohen, one of the last Jews here. The owner of Sarah Embroidery, she sells a variety of textiles, including Sabbath covers and gold-embroidered yarmulkes.

“We are only five Jewish families here,” she said. “My brother and sister are in Israel. All our people are there. All have gone to Israel.”

Walking along the water front, I spied an unusual sight — cantilevered Chinese fishing nets. Resting on teak and bamboo poles, they can haul in countless fish in one sweeping motion. By no coincidence, the outdoor fish market is close by. Prices are incredibly cheap. Buy a fish and have it grilled or fried at a fast food hut on the beach.

Perhaps the finest building in Cochin, the Mattancherry Palace, has been converted into a museum. Its spacious halls, coffered ceilings and mezzanine floors are impressive.

Presented as a gift to the Raja of Cochin by the Portuguese in the 17th century, the palace cum-museum is a treasure trove of stylized Hindu art, some of which is quite erotic; oil paintings of local rulers from 1503 to 1964; ceremonial royal textiles from headgear to robes; postage stamps and coins; sheathed daggers, swords and axes, and ivory-encrusted royal litters, which were held aloft by servants.

The palace, like Jewtown, conveys a palpable sense of place and time in Cochin’s colorful history.