As Marcellus, one of the sentries at Denmark’s royal castle in Shakespeare’s Hamlet might have said, “Something is rotten in the state of Argentina.”

The puzzling death of a prosecutor on Jan. 18 in Buenos Aires has fed speculation that he might have been murdered while gathering evidence in a high-profile terrorist attack more than two decades ago.

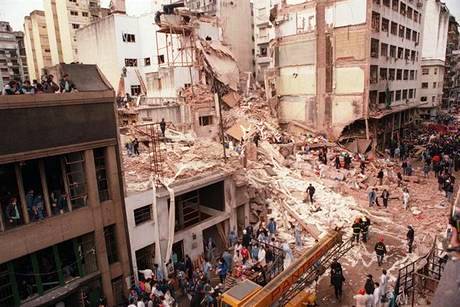

In 2004, Alberto Nisman was assigned to investigate the 1994 suicide bombing of a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires that left 85 people dead. He eventually traced the plot to Iran and its Lebanese ally, Hezbollah.

On October 25, 2006, Nisman formally accused the government of Iran of directing the bombing of the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association (AMIA) building, and Hezbollah of carrying it out.

But the Argentine government, not wishing to get involved in a diplomatic contretemps with Tehran, kept dragging its feet, instead signing an agreement with Iran to create a joint commission to investigate the bombing.

Nisman kept at it, though, and was set to testify to Argentina’s Congress on his report alleging that Argentina’s President, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, Foreign Minister Hector Timerman and other officials had covered up Iran’s connection to the bombing of the building.

They were accused, in a 300-page document, of setting up a “parallel diplomacy” to sign a “secret pact” with Iranian authorities that would lead to the exchange of Argentine grains for much-needed Iranian oil, and even an arms deal, to ease the country’s energy crisis and lack of hard currency.

But now, instead of presenting his findings to legislators, Nisman has been found dead in his apartment with a gun nearby. Government officials rushed to declare it a suicide.

But few believe it. Diego Guelar, a former Argentine ambassador to the United States, told CNN en Espanol that the suicide explanation is “ridiculous.” Patricia Bullrich, head of the legislative committee that invited Nisman to testify, agreed.

“In the days before his death on Sunday, the prosecutor was very active, very focused on the presentation he was going to give before Congress, in the evidence he was going to present and his mind made up about going forward with it,” Bullrich stated. “It’s hard to believe that he would have taken his own life.”

Nisman himself had told a reporter a day before his death, “I could end up dead from this.”

Following news of the death, some 2,000 protesters took to the streets near the presidential palace, the Casa Rosada, waving Argentine flags and holding signs proclaiming “Yo soy Nisman” (“I am Nisman”).

“The executive power is consolidating its dictatorship,” remarked protester Luciano Florio. “The judicial system cannot work independently when prosecutors are being killed.”

The 1994 attack, along with a 1992 suicide bombing of the Israeli embassy, which killed 29 people, remains an unhealed wound within Argentine society, particularly for its 180,000-strong Jewish community

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.