The last few months have seen major debates across Canada regarding the cultural appropriation of indigenous art and literature by non-natives.

The same issue has also emerged in Poland, especially in the southern city of Krakow, which I’m currently visiting.

As most readers know, Krakow is an incredibly beautiful and well-preserved medieval city, and the most popular tourist destination in Poland. The Stare Miasto (Old City), with its famous Rynek Glovny (Main Square), overflows with thousands of visitors day after day.

In the city’s old Jewish quarter, Kazimierz, one finds many renowned synagogues, the Galicia Jewish Museum, a Jewish cultural center, and other sites of Jewish interest.

The Rema synagogue is the burial place of Rabbi Moses Isserles, the renowned Talmudic scholar who codified much of Jewish law in the 16th century.

The sadness is everywhere but the indomitable spirit of the Polish people is also evident.

For the past 27 years, Kazimierz has been the site of an extremely popular Jewish Culture Festival. This year, the music and arts extravaganza, which ran for nine days from June 24 to July 2, attracted an estimated 30,000 visitors and residents.

The theme for this year’s festival was Jerusalem, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the unification of the city following the 1967 Six Day War. It featured more than 200 events, concerts, exhibitions, tours and talks, including a culinary program hosted by the National Library of Israel.

Before the Holocaust, Krakow was home to 65,000 Jews, who comprised about one-quarter of the city’s population. After the genocide, less than 4,300 remained. Today, approximately 1,000 Jews live in Krakow, but only about 200 identify themselves as members of the community.

The festival has introduced Jewish culture to a generation of Poles who have grown up without Poland’s historic Jewish presence.

When Janusz Makuch launched the festival, many Jews thought of Poland only through the lens of the Holocaust and Nazi death camps such as Auschwitz, some 65 kilometers from Krakow.

Makuch, who is not Jewish, wanted to counter that prevailing perspective through music and the arts that reflected the seven centuries of Jewish life in Poland rather than its absence.

It was a way, he said, both of honoring the dead and cdlebrating Jewish culture by bringing it back to life.

The festival’s unexpected success has raised the question of who speaks for Jewish culture.

As Jonathan Ornstein, executive director of the Jewish Community Center, told a journalist with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, it was Polish Catholics who have created and led an event that helped rekindle Jewish life in Krakow.

“One of the reasons Krakow is such a welcoming place for the Jewish community today is the work the festival has done,” Ornstein said. “Jews feel safe coming out of the closet as Jews.”

But does such philosemitism sometimes itself morph into antisemitism?

Alongside the official festival, a series of artistic and theatrical programs, known as Festivalt, was created by several Krakow-based international artists and performers.

In one such event, an actor playing the character of the “Lucky Jew” sat at a desk laden with an accounting ledger, an old-fashioned inkwell and a quill pen, offering good fortune in exchange for a few Polish zlotys.

The performance poked fun at the stereotypical trope of Jews as money handlers by bringing mythical images to life. But is this antisemitic or, as some Poles see it, a form of respect for Jews?

Confronting those complex questions through the arts is precisely the reason behind Festivalt, according to Michael Rubenfeld, one of the performers. Still, many Jews are uncomfortable with it.

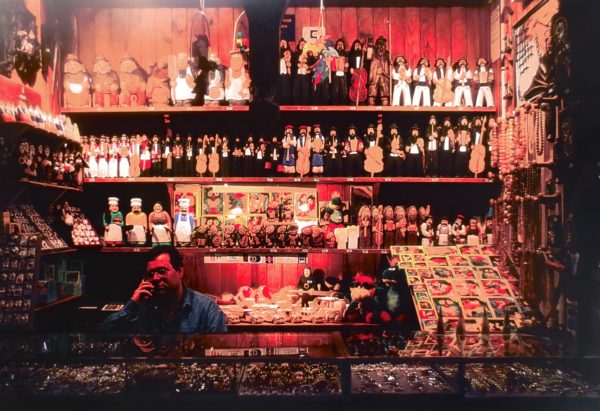

“Lucky Jew” figurines, called zydki, can sometimes be found in Krakow and elsewhere. They are wooden or clay statuettes of old Jewish men dressed like Hasidic rabbis, often with long beards and huge noses. They are sometimes holding a single coin, at other times a whole sack of money.

These figurines are said to have the ability to bring good fortune in monetary matters. They have become talismans as well as mementos of a bygone Poland in which Jews formed a merchant class.

Also popular are paintings of wizened old Jewish men counting coins. Scholars have traced their presence in Polish art back to the late 1800s.

Many Poles see them as innocent — or even positive. Woodcarver Adam Zegadlo said, “I make these wood carvings in honor of their memory.”

He insists that his aim is to not “let the traces of this ancient culture sink into oblivion.”

In any case, as tourism increased in post-Communist Poland, Polish artisans discovered there was a market for these figures, as likely to be bought by Jewish as non-Jewish visitors.

“In conversation with Polish artisans, Jewish visitors began to explain what they found offensive, and what nostalgic,” noted Greenwich, Connecticut Rabbi Jordie Gerson, after a visit to Poland a few years ago.

“The market shifted to reflect these preferences, and rabbis holding Torahs began to appear on store shelves alongside Jewish figurines playing in klezmer bands.”

Today, Jews and Poland’s Jewish past are treated with a mixture of animus and nostalgia, awe and hostility, she discovered, and the Holocaust tourism that helps support the Polish economy is both resented and revered.

So while some of these figurines remain clearly stereotypical, others are more marketable, since they romanticize Poland’s Jewish past.

After all, in many places, not a trace is left of the Jewish community that once existed there. So that blank space is filled today with images of Jews — figurines, pictures, magnets, postcards, and more.

Are these images positive or negative? Do they express affection, ridicule, fascination, or mourning? Do they divide Poles and Jews or do they tie them together? It probably can be either, depending on the viewer.

“They’re different things to different people,” according to Erica Lehrer, an anthropologist at Concordia University in Montreal.

She curated an exhibition at Krakow’s Ethnographic Museum in 2013 which sought to open a dialogue between these points of view.

In any case, they may be less visible these days, or so I found after spending more than three weeks in Poland this summer. They were on sale in many souvenir shops in Krakow, though.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.