The current crisis in Iraq is yet another replay of the historic power struggle and thinly-veiled animosities between Sunni and Shiite Muslims in the Middle East.

When the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria — an extremist Sunni group known as ISIS — invaded western and northern Iraq earlier this month, it enunciated its intentions in clear, unambiguous language.

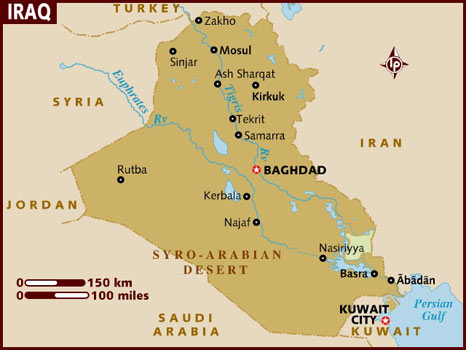

Its overarching goal, ISIS proclaimed, is to continue its offensive southward, capture Baghdad, topple the Shiite government of Prime Minister Nouri Kamal al-Maliki and establish the rudiments of a caliphate, or religious state, in both Iraq and Syria by erasing their post-World War I colonial borders.

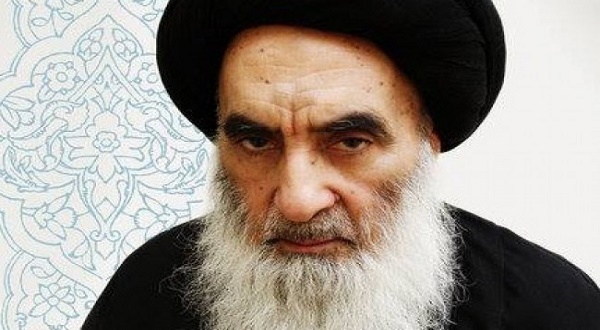

The Shiites, who form about two-thirds of Iraq’s population, are up in arms about that prospect, so much so that their grand ayatollah, Ali al-Sistani, has urged them to resist with all their might.

Since the United States may yet intervene by means of targeted air strikes, ISIS may not reach Baghdad and be driven out of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, as well as Tikrit, the home town of Iraq’s former ruler, Saddam Hussein.

President Barack Obama, who has already dispatched 300 military advisers to Iraq, is not likely to offer substantive military assistance unless Maliki establishes a much more inclusive government in which Sunnis and Kurds are given fairer representation. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, now in Baghdad, hopes to persuade Maliki that this course of action is long overdue.

Kerry is fighting an uphill battle.

Maliki’s divisive sectarian policies have embittered and alienated Sunnis, who controlled Iraq before the 2003 American invasion. His policies have also encouraged Kurds — the largest minority in the region without an independent state — to seize the city of Kirkuk and consolidate their autonomous enclave in the north.

In the face of this national emergency, one of the gravest crises to beset Iraq in the past decade, Sistani and Iran — the preeminent Shiite power in the Mideast — have called on Maliki to form a new national unity government that would be more reflective of Iraq’s ethnic mosaic. So far, he has not budged.

Under increasing internal and external pressure, Maliki may accede to this demand. Even if he does, he has already caused deep sectarian fissures in Iraq. He accused his Sunni vice-president of trumped-up charges of terrorism, forcing him to flee to Kurdistan. He sidelined the Sunni finance minister through an assassination attempt. He cut off funding to Sunni tribesmen who had played an instrumental role in defeating the Iraqi branch of Al Qaeda. He has fired high-level Sunni civil servants and senior Sunni army officers.

By no coincidence, ISIS — an offshoot of Al Qaeda under the leadership of Iraqi-born Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi — mounted its latest military campaign in league with disaffected secular Baathists loyal to the late Saddam Hussein, who was executed shortly after the United States occupied Iraq.

Politics creates strange bedfellows, to say the least.

The Baathists are led by Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, one of Saddam Hussein’s deputies and the highest-ranking figure in the old regime to elude capture by the Americans. Their twin goals are to restore Sunni supremacy and banish Iranian influence in Iraq.

In other words, they hope to turn back the clock and resurrect the status quo ante.

This explains why Iran has rushed to Iraq’s aid, urged Maliki to mollify Iraqi Sunnis and offered to work together with its arch enemy of three decades, the United States, to combat what Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has described as ISIS “terrorism.”

According to reports, the leader of Iran’s Quds Force, Qassim Suleimani, has already visited Iraq in a bid to organize Baghdad’s defences. Ironically, Suleimani mentored anti-American Shiite forces, notably Moktada al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army, from 2004 until 2008, the darkest years of the insurgency in Iraq.

Despite this history, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State William Burns discussed the Iraqi crisis with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif in Vienna recently. The pair were ostensibly in Vienna to resume negotiations on the nuclear issue, but tacked Iraq on to the agenda.

It remains to be seen whether the United States and Iran can work together harmoniously and effectively, since many of their interests do not and may never coincide. Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has come out strongly against U.S. intervention. But it should be recalled that the United States and Iran cooperated in Afghanistan following the catastrophic terrorist events of Sept. 11, 2001 in the United States.

Even under the best of circumstances, the Obama administration will be hard-pressed to contain surging Iranian influence in Iraq. For all his egregious faults, Saddam Hussein kept Iran at bay, fighting an eight-year war with the Iranians. Now that his regime is gone, and the majority Shiites are in charge, Iran’s clout in Iraq will surely grow.

Washington is under no illusions about Tehran’s strategic objectives in Iraq. But if the situation in Iraq is to be salvaged, the United States may have no alternative but to work with Iran.

That’s not the only problem confronting the United States as it ponders its options in response to ISIS’ battlefield successes.

ISIS swept into Iraq with a force of only several thousand fighters, some of whom are foreign volunteers from the Muslim world and the West. ISIS met little or no resistance as two Iraqi army divisions abandoned their posts and gave up the fight with a whimper. The army’s disgraceful performance was a reflection of inferior leadership, inadequate training and low morale.

Prior to its withdrawal from Iraq in December 2011, the United States spent approximately $25 billion to train and equip the Iraqi army, but judging by its abysmal performance earlier this month in Mosul, Tikrit and other places, the effort was largely in vain. Historically, the parallels between the Iraqi army and the doomed South Vietnamese army are ominously striking.

The question now is whether the United States wishes to invest billions more in an attempt to upgrade its capabilities.

Certainly, a far better fighting force will be required to roll back the gains ISIS has made of late and since January, when it captured Falluja and Ramadi, both of which are in Anbar province. Significantly, ISIS still holds these cities.

For the Americans, who lost 4,500 troops in the war and the subsequent insurgency, Anbar summons up painful memories. Nearly one-third of U.S. casualties in Iraq were sustained in that province, particularly in two battles for control of Falluja.

ISIS, which seems more radical than even Al Qaeda, has been fighting a two-front battle for the past few years.

In the civil war in Syria, ISIS has taken a leading role against the mainly Shiite forces of President Bashar al-Assad. Six months ago, ISIS captured the Syrian town of Raqqa, which lies astride the oil fields of eastern Syria. Since then, ISIS has financed its operations by oil sales, some to the Syrian government.

Before its stunning capture of Mosul, ISIS stormed the Iraqi city of Samarra, which contains one of the holiest shrines in Shiite Islam. The army, backed by helicopter gunships, routed ISIS. But within several days, ISIS was on the rampage again, creating the present crisis that threatens Iraq’s future as a viable and united state and reminding Muslims that the two main branches of Islam are virtually at war.