Cornelius Gurlitt, the reclusive German art collector whose father acquired a treasure trove of 19th and 20th century European master works under questionable circumstances during the Nazi era, passed away in Munich on May 5. He was 81 and had been suffering from a heart ailment.

Gurlitt’s death closes a chapter in the history of Nazi-looted art, but opens up a new debate regarding the status of most of the 1,280 paintings and drawings found in his apartment nearly two years ago.

Focus, a German newsmagazine, broke the story in November 2012, reporting that the German government had been aware of their existence but had chosen to keep the information secret. Focus‘ scoop embarrassed Germany, since many of the works in Gurlitt’s possession had been owned by European Jews who were forced to sell them at deflated prices. In still other cases, Jewish-owned art collections were simply expropriated by the Nazi regime after their proprietors emigrated or were murdered in the Holocaust.

According to a report in the May 8th edition of The New York Times, Gurlitt left hundreds of his paintings and drawings to the Kunstmuseum in Bern, Switzerland. A court in Munich in charge of his affairs will now have to ascertain whether there are heirs who intend to contest his will. Consequently, the ultimate fate of the Gurlitt collection, currently held by the German government in undisclosed locations and by his estate, is still up for grabs.

About a month before he died, Gurlitt reached an important agreement with the authorities. He would be permitted to keep hundreds of pieces he had apparently acquired legitimately. As for the rest, an international commission of experts, appointed by Germany, would have one year to investigate their provenance. This agreement surprised observers, as Gurlitt had previously stated that he would never give up a single piece.

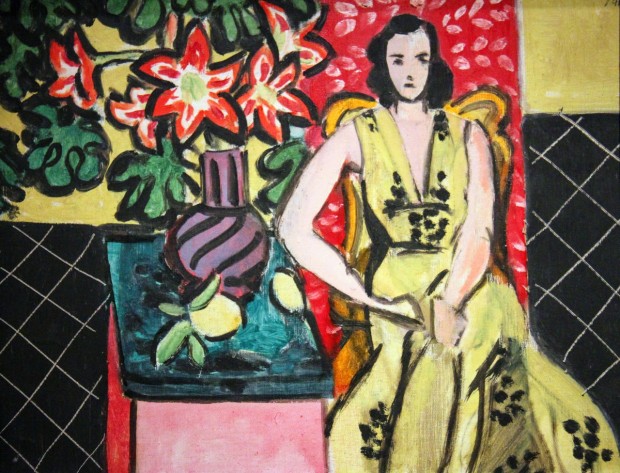

The works in Gurlitt’s collection are eclectic, having been painted or drawn by, among others, Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse, Otto Dix, Honore Daumier, Ernst Kirchner and Max Liebermann.

The Munich Art Trove, as it is known today, was amassed over a 12-year period by Hildebrand Gurlitt, Cornelius’ father. Born in 1895 in the eastern city of Dresden, he hailed from a cultured family of artists and intellectuals.

Shortly after Adolf Hitler assumed power as Germany’s chancellor in 1933, Hildebrand lost his job as director of the Kunstverein museum in Hamburg. Hildebrand’s preference for modern art was deemed a problem by his bosses, as was his partial Jewish ancestry, stemming from his grandmother, Elisabeth.

With German Jews being persecuted and driven out of Germany, Hildebrand seized his opportunity. He began buying art at radically depressed prices from Jews who were either planning to leave or remain in Germany. He would later claim that he had never bought “a picture that wasn’t offered to me voluntarily.”

Despite his designation as a Jew under the 1936 Nuremberg race laws, Hildebrand was granted special permission by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, a rabid antisemite, to sell 16,000 modern paintings that the Nazis had branded “degenerate” and beyond the pale.

During World War II, Hildebrand visited France, Belgium and Holland in his capacity as an official art dealer. He scooped up valuable works, some of which were destined to be exhibited at a museum that was being built in Linz, Austria, in Hitler’s honour.

One of the canvases, Seated Woman/Woman Sitting in Armchair, was painted by Matisse and was taken from the collection of Paul Rosenberg, an eminent Jewish art dealer in Paris.

It’s unclear how Hildebrand acquired paintings he had supposedly purchased on behalf of the Nazi regime. The story is still quite murky. This much, though, is certain. After the war, he was placed under arrest by the American occupation army in Germany, charged with being a Nazi collaborator.

Gurlitt claimed that he had been a victim of Nazi antisemitism, that he had no alternative but to cooperate with the Nazis and that he had saved precious “degenerate” works from destruction.

Hildebrand was released from prison in 1948, but his art collection was confiscated. In 1950, however, it was returned to him. In postwar West Germany, he became a prominent art dealer. After he was killed in a car accident in 1956, critics hailed him as one of the key figures in the postwar German art scene.

By all accounts, Cornelius, his son, never held a job and lived off the paintings. The last one he sold, Lion Tamer by Max Beckmann, fetched $1.1 million (U.S.) in 2011.

Ironically, the Gurlitt collection was discovered accidentally in a tax evasion case that came to light after customs officials caught Cornelius with an unusually large sum of cash aboard a train bound from Switzerland to Germany.

The upshot of the Gurlitt affair is that works of art that were plundered or acquired by devious means will be returned to their rightful owners, says German Culture Minister Monika Gutters, who has promised to address restitution claims by the descendants of the victims.

Certainly, Germany will be judged by the manner in which it handles this file.