Germany’s last election after Adolf Hitler’s accession to power was held on March 5, 1933. The Nazis captured 288 out of 647 seats in the Reichstag, winning 43.9 percent of the vote and establishing the national socialist party as the largest parliamentary bloc. Although 17 million voters were mesmerized by his vision of Germany, most Germans were not followers of the fuhrer, and a tiny minority worked tirelessly against his racist, totalitarian regime.

The small band of brave and principled Germans who risked their lives to topple Hitler, before and during World War II, are profiled by Gordon Thomas and Greg Lewis in a substantive book, Defying Hitler: The Germans Who Resisted Nazi Rule (Caliber). These dissenters paid a heavy price for the courage of their convictions.

Among them were Arvid Harnack, a Ministry of Economics official who passed official secrets to the Soviet Union and the United States; Henning von Treschkow, an army colonel who was involved in the abortive 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler, and Hans and Sophie Scholl, a brother and sister who belonged to the White Rose resistance group.

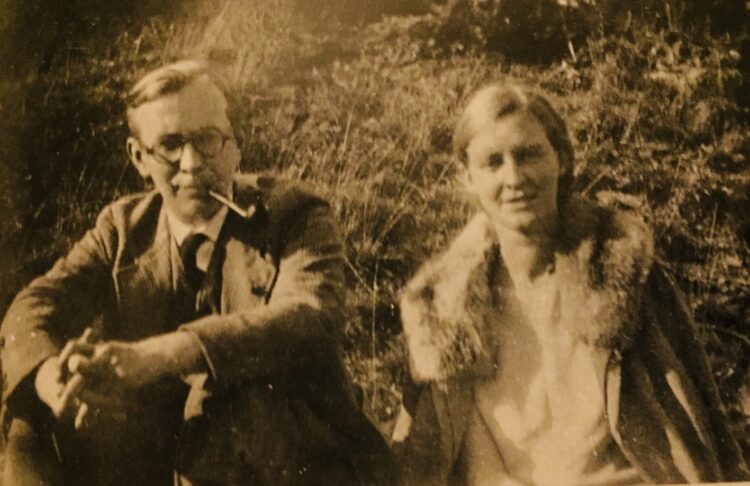

Harnack and his American wife, Mildred Fish, were members of an anti-Nazi socialist underground movement. From the moment he joined the civil service, he was determined to undermine the Nazi government. He became a Nazi Party member so that his loyalty would not be questioned. Considering himself neither a spy nor a traitor, he was a loyal German who despised the Nazis with every fibre of his being.

The information he conveyed to Moscow and Washington concerned Germany’s rearmament program, its economy, its trade agreements with foreign countries, and its attitude toward the non-aggression pact Germany had signed with the Soviet Union on the eve of the war.

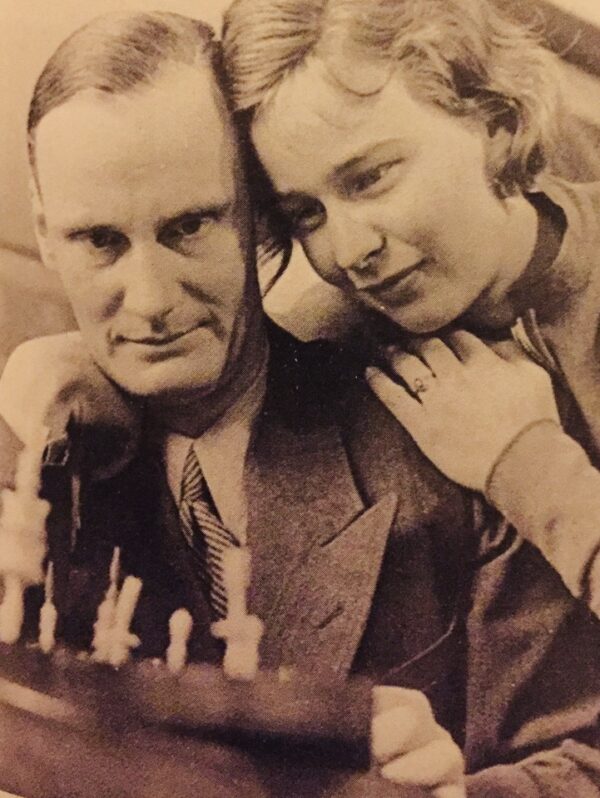

Harro Schulze-Boysen, an employee of the Air Ministry, warned the Allies that Germany intended to invade the Soviet Union. His wife, Libertas, who had been a Hollywood film studio publicist in Berlin and an enthusiastic Nazi until she met her husband, worked for the Ministry of Propaganda. She amassed footage of Nazi crimes in Poland and the Soviet Union.

The Scholls soured on Nazism over its harsh mistreatment of German Jews, and recruited like-minded followers such as Alexander Schmorrel and Christoph Probst into White Rose. At great risk to themselves, they wrote and distributed leaflets which lambasted the morality of the regime.

“Since the conquest of Poland, three hundred thousand Jews have been murdered … in the most bestial way,” one leaflet read. It went on to say that it was “the holiest duty of every German to destroy (the) beasts” who had committed these crimes.

Another leaflet accused Hitler of being a “charlatan” and advocated a ceasefire and negotiations with the Allies so that the war could be ended.

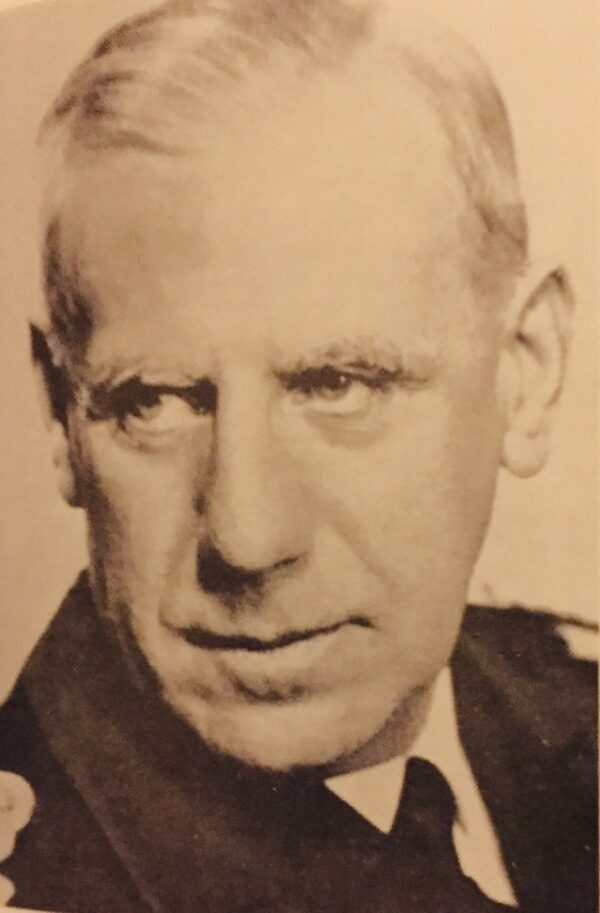

Surprisingly, the authors cite several high-ranking Nazi government figures who might ordinarily be excluded from a checklist of anti-Nazi activists: Wilhelm Canaris, the head of the military counter-intelligence agency, the Abwehr; Hans Oster, a senior figure in that organization, and Ludwig Beck, a former chief of staff of the armed forces.

Fiercely nationalistic, Canaris was disdainful of the Nazis, tried to purge the Abwehr of SS influence, and allowed his colleagues to build an anti-Nazi clique within it. Oster loathed the Nazis’ anti-Jewish policy and was convinced that Hitler had to be eliminated so as to cleanse Germany of Nazism. Beck considered the Nazis vulgar and opposed Hitler’s aggressive foreign policy.

Hans von Dohnanyi, a lawyer who knew Harnack, was recruited by Oster into the Abwehr as an advisor on foreign and military affairs. He compiled a Chronicle of Shame of the regime’s “unchristian” actions in Poland.

The Kreisau Circle was composed of upper-class Germans who believed that the survival of Europe was dependent on Germany’s defeat, and that the values of the Nazi successor state should be based on Christianity and socialism. Among its members were Helmuth James Graf von Moltke, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Adam von Trott zu Solz.

Carl Goerdeler resigned as mayor of Leipzig in 1936 after the Nazis removed a statute of the composer Felix Mendelssohn, whose Jewish family had converted to Christianity. From that point forward, he was a critic of the Nazi regime.

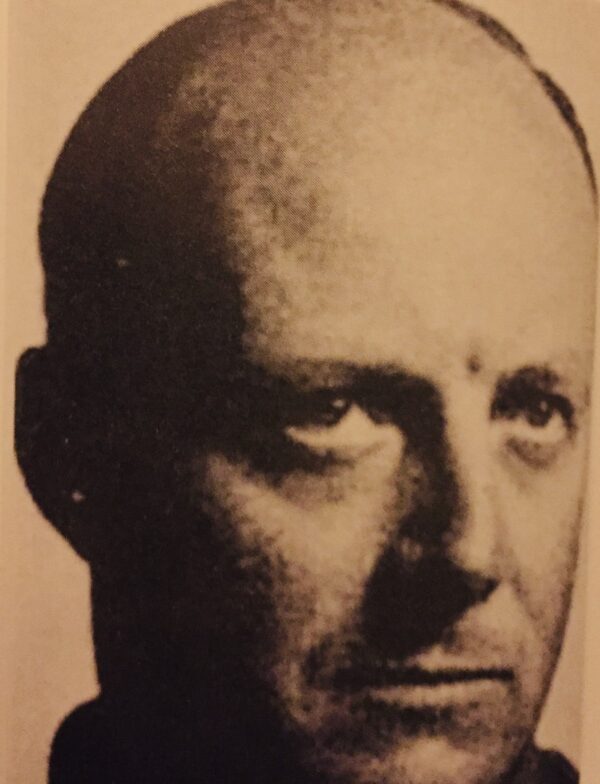

George Elser, a cabinetmaker who supported the Communist Party, was the first German who seriously tried to assassinate Hitler. In 1939, he placed a bomb in a Munich pub where Hitler was due to speak to old comrades. Hitler left the premises 13 minutes before the device exploded, killing eight people and wounding more than 60.

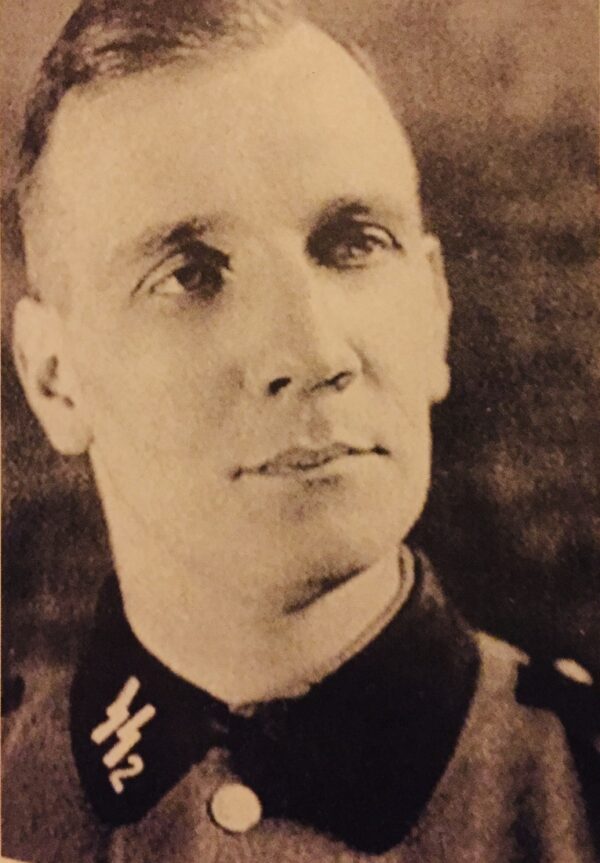

The authors describe Kurt Gerstein, a devout Christian, as perhaps “the most morally complicated” of all the anti-Nazi resisters. “Gerstein would speak out against the Holocaust — but would also be part of it,” they write.

Repulsed by Kristallnacht, the nation-wide pogrom which broke out in November 1938, he decided he could be an effective opponent of Nazism only from the inside. Joining the Waffen-SS in 1940, when he was 30, he was put in charge of delivering Zyklon-B gas to extermination camps in Poland. Gerstein sabotaged one delivery, but his gesture had no effect whatsoever on the Holocaust.

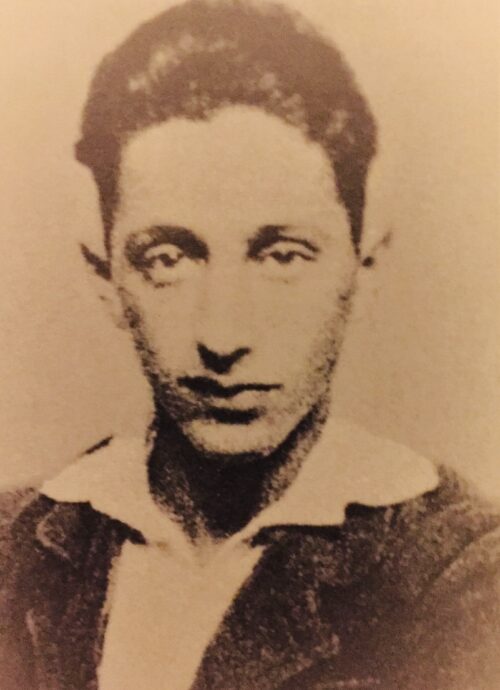

Herbert Baum, a German Jewish forced laborer and anti-fascist, played a role in the production of pamphlets which mocked the Nazi leadership and the distribution of fake French, Belgian and Dutch identity cards and passes that the remaining Jews of Berlin could use to try to pass as Aryans.

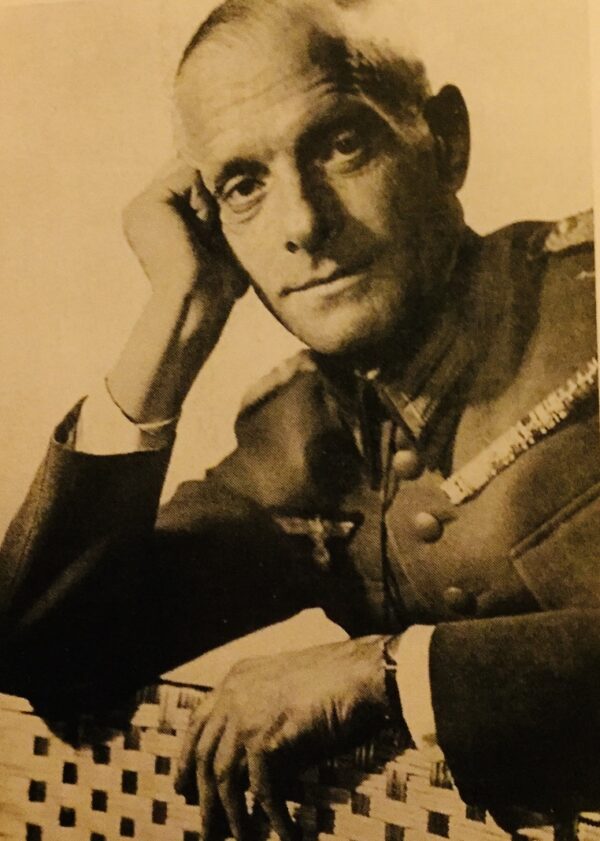

Henning von Treschkow, a senior staff officer of Army Group Center, grew disillusioned with the Nazis after reading top secret reports of atrocities perpetrated by the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile killing squads unleashed in Poland, the Baltic states and the Soviet Union. Having concluded that the Wehrmacht had been dragged into a genocidal war on behalf of the Nazi Party, he began planning a coup d’état with the assistance of some 30 colleagues.

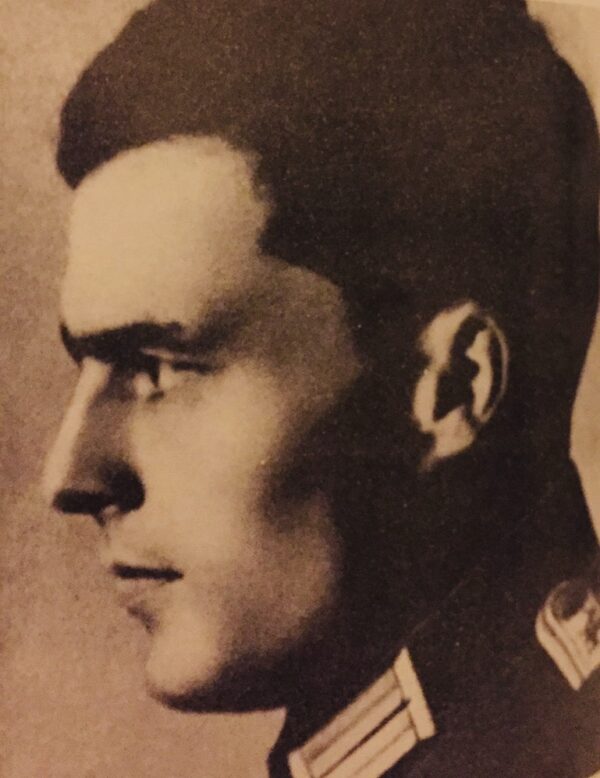

One of them, Claus von Stauffenberg, was a seasoned officer disgusted by the Nazi mass murder of Soviet Jews. Determined to kill Hitler and form a new government, he had a keen appreciation of the enormity of his mission. “The man who has the courage to do something must do it in the knowledge that he will go down in German history as a traitor,” he told friends. “If he does not do it, however, he will be a traitor to his own conscience.”

Having learned that Hitler planned to attend a meeting in East Prussia on July 20, 1944, von Stauffenberg planted a bomb in the appointed conference room. The blast shattered windows, destroyed a wall and killed three army officers and injured 20. Hitler, though wounded, survived. “I am invulnerable, I am immortal,” he boasted to his doctor.

Within less than a year, Red Army troops conquered eastern Germany and Hitler fatally shot himself in his Berlin bunker.

Many anti-Nazi dissenters, from von Stauffenberg on down, were summarily executed by the regime, so it’s debatable what tangible objectives they actually achieved. After all, Hitler’s regime finally collapsed only after Germany had been soundly defeated by Allied forces. Yet their decency, courage and steadfastness should be applauded and never forgotten. Against all odds, as Defying Hitler states, they confronted the Nazi beast as best they could.