To put it bluntly, Holocaust denial is the stock-in-trade of antisemites. In their zeal to defame Jews, defend Nazi Germany and rehabilitate Adolf Hitler, they dredge up factually baseless arguments.

Their claims are absurd: The number of Jewish victims was drastically inflated to benefit Jews and Israel. Jews succumbed to disease and were not murdered on an industrial scale by the Nazis. The gas chambers and crematoria never existed. Jews, far from having been uniquely victimized, were among the millions of casualties of World War II. Indeed, the Holocaust was a hoax.

Or so Holocaust deniers say.

In her book, Denying the Holocaust (1993), American historian Deborah Lipstadt elaborated upon these themes. In passing, she singled out David Irving, a specialist on the Third Reich, as a denier. Irving, a British historian, sued Lipstadt and her publisher, Penguin, for defamation, claiming she had damaged his reputation and imperilled his livelihood.

The case went to trial in London in 2000. Irving lost after Lipstadt’s brilliant legal team proved beyond a reasonable doubt that he was a racist and had deliberately misrepresented, distorted and manipulated the historical record. Lipstadt wrote a book about it, History on Trial: My Day in Court with a Holocaust Denier, and now Mick Jackson has brought this cause celebre to the big screen.

Denial, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in Toronto and due to open in theaters in North America in early October, is a solid and absorbing movie starring Rachel Weisz as Lipstadt and Timothy Spall as Irving.

Rather than being didactic or boring, Denial is riveting and fast-paced thanks, in part, to David Hare’s lucid script. It’s also an important history lesson, demolishing the myth that the Holocaust is a figment of the Jewish imagination. If you deny the Holocaust, you may as well question the veracity of any event.

Denial gets under way as Lipstadt, a professor of Holocaust studies and Jewish history at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, explores the meaning of Holocaust denial with her students. The film then cuts to a speech she’s giving at another university. Lipstadt explains why she won’t debate deniers like Irving, who, she says, mangle the truth for their own malevolent ends.

At this juncture, Irving dramatically appears in the audience. He contends she cherry picks facts so that they align with her opinions. And he distinguishes between “real history” and “manufactured history.” He offers $1,000 to anyone in the room who can offer “proof” of the Holocaust. It’s a dramatic confrontation, presaging Irving’s formal challenge to Lipstadt’s credentials as a credible chronicler of the Holocaust.

Having decided to expose Irving as a falsifier and liar, Lipstadt hires a legal team consisting primarily of Anthony Julius (Andrew Scott), a high-profile London solicitor, and Richard Rampton (Tom Wilkinson), a Scottish barrister. Julius and his assistants will assemble the research materials, while Rampton will represent Lipstadt in court. Lipstadt, a feisty, self-confident woman, has qualms about this process. A court of law is “a lousy place” to judge history, she complains.

Conservative members in London’s Jewish community express doubts, too. They prefer to “settle” with Irving so as to deny him a platform to espouse his noxious views.

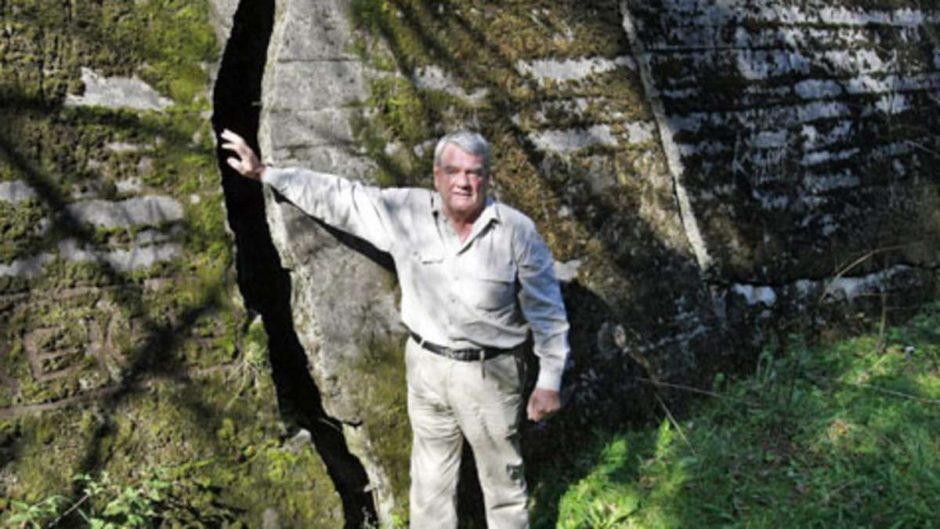

The film shifts to the former Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland, where Rampton, accompanied by Lipstadt and the Canadian historian Robert Jan van Pelt, examines the evidence on the ground. Rampton requires irrefutable “proof ” that mass murder took place here. His methodical method annoys Lipstadt. “I thought we wern’t going to try the Holocaust,” she says in exasperation. “It’s about forensics,” counters his assistant. These scenes, shot during the gloom of a Polish winter, are bleak and revealing.

Lipstadt is also upset by the news that she will not be able to testify at the trial. The focus should remain exclusively on Irving so that he will be exposed as an antisemite and liar, Julius explains. Nor is she initially pleased to learn that a judge, rather than a jury, will deliver the verdict.

The courtroom scenes are charged with passion as Rampton and Irving, representing himself, clash. Irving claims he’s “drawn attention” to the Holocaust in his books, but Rampton proves he’s manipulated the facts to suit his ideological beliefs. At another point, Irving, having been caught in a lie, lamely claims he’s not a Holocaust historian in the strictest sense of the word.

Further tension boils to the surface when Lipstadt insists that Holocaust survivors should take the stand against Irving. The “voice of suffering” must be heard, she says. Julius resists, explaining it could be a risky strategy.

As she discovers, the tactics employed by her lawyers were extremely useful and effective. Irving was unmasked, leaving his claim to honesty and professionalism in tatters.

Weisz, a British actress, delivers a plausible performance as the gutsy Lipstadt. The other members of the cast, particularly Spall, acquit themselves with panache as well.

Much to its credit, Denial deals with the serious problem of Holocaust denial clearly and effectively. But as one might imagine, Irving is merely the tip of a massive iceberg. Although he was cut down to size in a court, his followers on the margins of society still disseminate his lies.

Holocaust denial is hardly a spent force, Lipstadt’s victory notwithstanding.