Persecuted Jews have found a safe haven in the Ottoman Empire and its successor state, Turkey, for centuries now. This is easily overlooked, or even forgotten, as political tensions continue to flare between Turkey and Israel.

Victoria Barrett’s documentary, Desperate Hours, makes this point crystal clear. Although it was made more than a decade ago, it’s as fresh today as the moment it was released. Like its sister film, Turkish Passport, which came out in 2011, it underscores an unassailable truth. During two of the darkest periods in Jewish history — the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 and the persecution of Jews by Nazi Germany and its fascist allies — the Ottoman Empire and Turkey were there to lend Jews a helping hand.

Desperate Hours covers the Ottoman era in a matter of minutes, explaining that Spanish Jews were welcomed to settle in the far-flung empire because the pragmatic sultan was certain they would be productive and loyal citizens, which turned out to be the case.

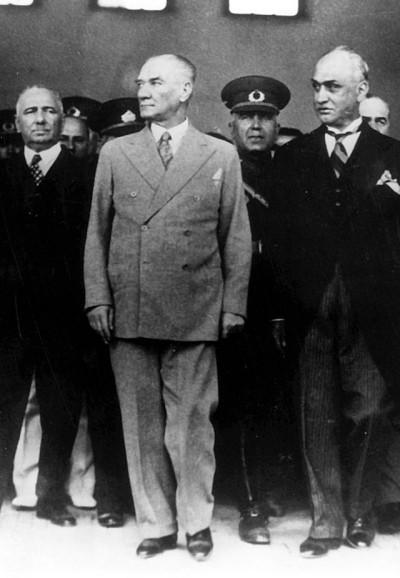

Fast forwarding to 1933, the year Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, the film briefly focuses on Kemal Ataturk, Turkey’s revered and Western-oriented leader (who died in November 1938 as Kristallnacht convulsed Germany).

Requiring European-trained scholars to fill positions in a newly built university, he invited 200 Germans — two-thirds of whom were Jews — to Turkey, a Muslim secular state. Many of the refugees were given positions in Istanbul University, which became the best “German” university outside Germany.

One of the exiled academics, an architect, designed the parliament, the presidential palace and the ministry of defence in Turkey’s capital, Ankara.

Talk about leaving a legacy.

These exiles formed a culturally distinct, close-knit community within Turkish society. “It was a very secure atmosphere,” recalls one of the professors who took advantage of Turkey’s hospitality.

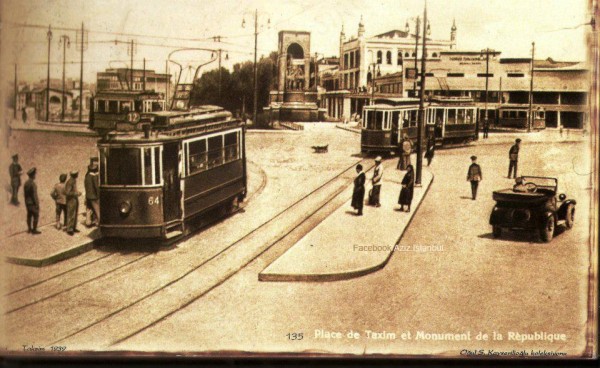

By 1941, Germany had advanced into the Balkans, with German troops stationed perilously close to the Turkish border. Fearful Turkish Jews assumed that Germany might violate the sovereignty of Turkey — a neutral state — so as to use it as a land route to invade the Soviet Union. This apprehension was dispelled by Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union through European nations like Poland and Romania.

At this juncture, Desperate Hours shifts its attention to German-occupied France, where about 10,000 Jews of Turkish origin lived. To the best of their ability, Turkish diplomats in France protected such Jews, some of whom recall their experiences in the film.

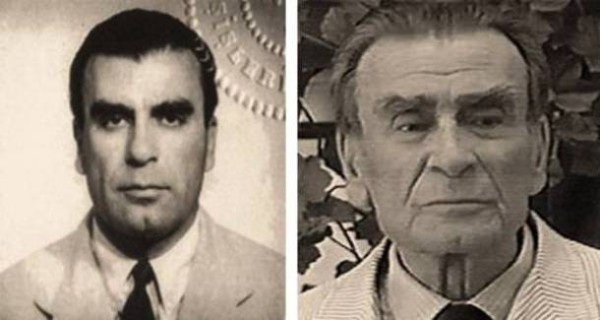

Turkey’s vice-consul in Marseilles, Necdet Kent, personally intervened to save at least 50 Jews aboard a German train bound for a Nazi concentration camp. On the island of Rhodes, Selahattin Ulkemen, the Turkish consul general, rescued a similar number of Jews. After the war, he was recognized as a righteous gentile by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust research and educational center in Jerusalem.

The Turkish government was helpful on another front as well, permitting Jewish Agency officials to funnel imperilled Jewish refugees from Turkey to Palestine, a British mandate. Altogether, about 20,000 Jews reached Palestine by way of Turkey.

Tragedy struck after the SS Struma, a ship filled with more than 700 Romanian Jews, reached Istanbul. With Britain exerting pressure on Turkey to stop the vessel from proceeding to Palestine, the Turks finally towed it out to sea. Under still mysterious circumstances, a Soviet submarine sunk the SS Struma, with only one survivor.

Desperate Hours barely mentions the notorious wealth tax Turkey imposed on non-Muslim citizens during the war. It should have explored this issue at some length for a fuller appraisal of Turkey’s policy toward its minorities.

Barrett has high praise for Angelo Roncalli, the Vatican’s envoy in Istanbul and a future pope. By all accounts, he played a positive role in assisting Jews in Greece and Bulgaria, but she provides no details.

As Barrett reminds us, Istanbul was the venue, in 1944, of one of the murkiest episodes of the war. Heinrich Himmler, the SS chieftain, offered the Allies a deal in which Germany would release one million Jews in exchange for 10,000 military-grade trucks.

The Germans sent the Hungarian Jewish leader Joel Brand to Istanbul to consummate the agreement, but the Allies rejected it. As this foreign intrigue played out, Germany, in cooperation with Hungary, dispatched more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau for extermination.

A catastrophe engulfed the Jews of Europe during the Holocaust, but as Desperate Hours points out, Turkey was a glimmer of light in the darkness.