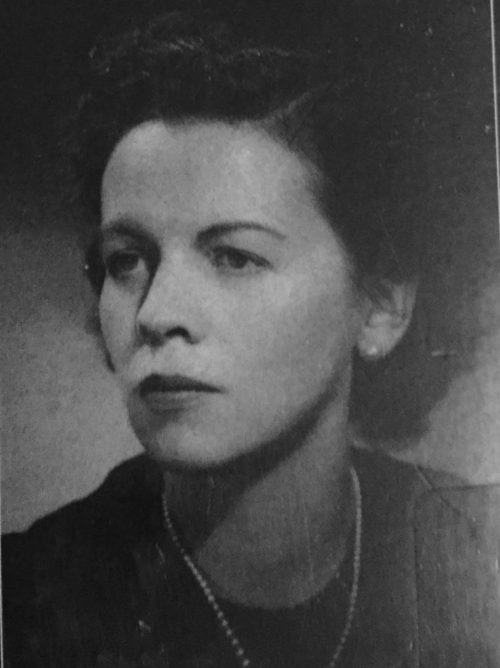

Most Canadians have never heard of Gwethalyn Graham’s novel, Earth And High Heaven, which was published 75 years ago this year. Although it was a phenomenal commercial success and a literary sensation in its day, it has almost been forgotten today.

Published in 1944, when Canada had been at war for five years and Nazi Germany had already managed to murder nearly six million European Jews in the Holocaust, it won the Governor General’s Award and was the first Canadian novel to top bestseller lists in the United States. Since then, it has sold one and a half million copies, an astronomical figure, and been translated into 18 languages.

The Hollywood movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn bought the rights for a whopping $100,000, but never converted it into a film because a rival studio beat him to the punch by making Gentleman’s Agreement, starring Gregory Peck, in 1947. Like Gentleman’s Agreement, adapted from a novel by Laura Hobson, Earth And High Heaven turns on the always sensitive issue of antisemitism.

Graham’s novel is a scathing critique of antisemitism in Canada, which today portrays itself as tolerant and inclusive. Back in the 1940s, however, Canada was a very different place. Antisemitism was common, and although there was a vibrant and growing Jewish community in Canada, the Canadian government was reluctant to admit new Jewish immigrants, as the historians Harold Troper and Irving Abella point out in their path-breaking 1982 work, None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948. As they disclosed, only about 5,000 Jewish refugees were allowed into the country during the period between Adolf Hitler’s accession to power in Germany and the end of World War II.

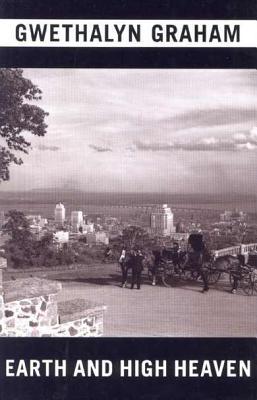

Earth And High Heaven unfolds over several months in Montreal in 1942 and revolves around the fraught romance between Marc Reiser, a Canadian-born Jewish lawyer from northern Ontario, and Erica Drake, a journalist from a well-to-do Protestant family in Westmount, a wealthy neighborhood mainly inhabited by old money people of British stock.

A captain in the Canadian army waiting to be sent abroad to war, Marc meets Erica at a cocktail party. He is 33 and she is 28. They’re introduced to each other by Rene de Sevigny, Marc’s French Canadian acquaintance whose sister is married to Erica’s older brother. Ordinarily, an invisible border separates Montreal Jews and Christians, who normally do not mix socially after hours. Indeed, as Graham writes in the first page, “there is not much coming and going” between the two groups. Marc and Erica will break this mould, with all its attendant consequences.

Marc’s father, Leopold, is an Austrian who settled in Canada in 1907, and now runs a small timber mill in the town of Manchester. Erica’s father, Charles, is the president of a company that imports sugar, rum and molasses from the West Indies.

As described by Graham, Erica is “not only lovely to look at, she was the sort of person whom you liked and with whom you felt at ease from the first moment.” Erica is intelligent, generous and empathetic. Marc is physically graceful, “obviously sensitive and very intelligent.” He “does not look particularly Jewish … or foreign.”

Marc identifies himself as a Jew to Erica shortly after their first meeting. He tells Erica, a liberal, that the janitor of a new apartment building on Cote des Neiges Road refused to rent him a flat because he is Jewish. “He said it so matter-of-factly that Erica almost missed it, and then it was as though it had caught her full in the face,” Graham writes.

Charles, being an anti-Nazi and a democrat, appears to be tolerant and free of malice. But when Erica informs him about Marc, Charles bristles. “Sounds like a Jew,” he says. He’s charming, she counters. He replies, “I don’t usually care much for Jewish lawyers.”

Charles’ prejudiced response alarms Erica. “We Canadians don’t really disagree fundamentally with the Nazis about Jews,” she says. “We just think they go a bit too far.”

In another key passage, Charles explains his bias against Jews: “You know as well as I do that among the people we know — your mother’s friends, my friends, even your own friends for that matter, or most of them at any rate — a Jewish lawyer sticks out like a sore thumb. He just doesn’t fit; from a social point of view, he’s unmanageable — makes everyone else feel awkward …”

Charles elaborates: “The point is that once they get a foot in your door, if you treat them the way you would anyone else, either they deliberately take advantage of it, or simply misunderstand it, and before you know it, they’re all the way in and there’s no way of getting rid of them.”

He claims his perception is all too common in the high society circles he frequents. “I’ve had a great deal more experience of the world than you. I’ve no objection to Jews, some of the ones I know downtown are very decent fellows, but that doesn’t mean I want them in my house anymore than they want me in theirs — it works both ways, don’t forget that …”

When Erica insists she’ll keep seeing Marc, he digs in his heels. “It’s not a question of being fair or unfair. There’s no sense in going out of your way to create a situation which might turn out to be very awkward for everyone, when you can so easily avoid it.” Charles adds that Marc’s ulterior interest in his daughter is clear: “to improve his social, and indirectly, his professional standing.”

Margaret, Erica’s mother, concurs with her husband. “No one in his senses could possibly imagine that you and Marc have even a reasonable chance of being happy. There’s too much against you.” To Margaret, the ingredients of a successful marriage are a “community of tastes, interests, and a similarity of viewpoint and background.” As far as she is concerned, Erica’s affair with Marc is merely a transitory infatuation.

Erica is hardly surprised by her parents’ animosity toward Marc, whom they have not even met, much less spoken to. As Graham writes, “She had heard it all before from various other people, and had grown up in a society in which almost everyone threw off derogatory remarks about ‘The Jews,’ often from sheer force of habit.'”

Erica is frustrated by their racism. “She knew Marc, she was in possession of the evidence, of the actual facts concerning Marc Reiser, and between these facts and her father’s statements about Jews, there was simply no connection.”

She realizes that the doors of ritzy clubs will be slammed shut if she marries Marc, but this does not bother her in the least. “I don’t care about clubs,” she declares. Later, in a conversation with Marc, Erica says, “What my father wants is unconditional surrender to a set of prejudices and a bunch of filthy conventions which are hopelessly out of date!”

Marc’s father, an underdeveloped character in the novel, rails against their relationship too. “You aren’t going to do her any good by marrying her,” he says. When Marc insists their marriage will work out, his father disagrees, saying that Christians are “hopelessly different.”

Erica’s sister, Miriam, and Marc’s brother, David, are the only ones who unequivocably support them. Miriam believes there is no better person for Erica than Marc. David, a physician, urges him to stick by Erica and his principles.

Although he loves Erica, Marc fears he will ruin her life if he marries her. Erica cannot bear the thought that “there is no place for you and me.”

In Earth And High Heaven, Graham, who died in 1965, brings these characters to life and draws a convincing portrait of an insular country riven by religious, ethnic and class differences. In the 1940s, a mixed couple like Marc Reiser and Erica Drake had to struggle for acceptance. But in the seven and a half decades since the publication of her novel, Canada has changed tremendously and deveoped into a nation where differences are usually respected, if not celebrated.

Antisemitism still exists, of course, but it is no longer the insurmountable problem it was in 1944 when Graham’s book first appeared