Before the advent of German reunification in 1990, two sovereign states, West Germany and East Germany, faced each other as bitter, implacable rivals. West Germany, a democracy formed in 1949, was aligned with the United States and the West. East Germany, a communist state which emerged in the same year, was a member of the Soviet bloc. Their radically different political orientations and agendas affected their respective attitudes and policies toward Israel, writes Jeffery Herf in his superb book, Undeclared Wars With Israel: East Germany and the West German Far Left 1967-1989 (Cambridge University Press).

This is an important and cogent work of scholarship, the first in any language on this topic to draw on such a multitude of sources — the archives of East Germany, the files of the United States and West Germany, and documents culled from the Israeli government, the West German Jewish community, the West German far-leftist movement, the Arab states and the Palestinian armed organizations

Herf — a professor of history at the University of Maryland and the author of Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in the Two Germanys and Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World — draws sharp comparisons between West Germany and East Germany in this deeply-researched 493-page volume.

In line with its policy of coming to terms with the Nazi past, West Germany offered financial restitution to Holocaust survivors and the newly-created state of Israel, established diplomatic relations with the Jewish state and embarked upon a secret program of sending military equipment and munitions to Israel.

The unwritten eleventh commandment in West Germany was that no German government or political group “should kill or harm any more Jews or lend assistance to anyone else who was killing or harming Jews,” says Herf. Successive West German chancellors, like Konrad Adenauer and Ludwig Erhard, hewed to this policy, even though they tolerated the presence of former Nazi officials in the civil service.

East Germany, following in the path of the Soviet Union, adopted a hostile policy to Zionism as an idea and to Israel as a reality. Left-wing extremists in West Germany, belonging to organizations ranging from the Red Army Faction to the Revolutionary Cells, turned against Israel as well and collaborated with Palestinians intent on destroying it.

As Herf points out, East Germany, known as the German Democratic Republic (DDR), had a much greater impact on the Middle East than these leftists. The East German government could deploy state power — armed forces, a diplomatic corps and intelligence agencies — to affect the balance of forces in the region.

Although a minority of East German communists desired cordial relations with Israel, the orthodox majority rejected that approach. During the early 1950s, when the Cold War intensified, communists deemed sympathetic to Israel were purged from positions of influence, or sent to prison. Denouncing Israel as an ally of U.S. imperialism, and rejecting Zionism as an anachronistic and regressive ideology, East Germany refused to pay Holocaust restitution to the Israeli government.

East Germany’s hostility was such that it had the dubious distinction of being the only member of the Warsaw Pact not to establish formal bilateral relations with Israel. As East Germany demonized Israel, it formed a solid relationship with groups like the Palestine Liberation Organization and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

“In one of the bitterest ironies of this era, the communists and the leftist movements transformed the language of anti-fascism that the world associated with the war against Nazi Germany into a rhetorical arsenal to use against the Jewish state,” observes Herf.

To ideologues in East Berlin, Zionism was “a chauvinist ideology of the Jewish bourgeoisie,” while Israel was seen as an anti-communist bulwark against the Arab national liberation movement.

Herf contends that the verbal assaults mounted against Israel by East Germany and the far left in West Germany transcended criticism of this or that Israeli policy. Essentially, they rejected Israel’s “moral legitimacy and thus its right to exist as an independent state,” he notes.

In effect, they were at war with Israel.

The key figures in East Germany’s ideological and political battle against Israel were, first and foremost, Walter Ulbricht, the head of state from 1950 to 1971, and Erich Honecker, his successor, who ruled from 1971 to 1989. Politburo members Herman Axen, Gerhard Gruneberg and Willi Stoph also played key roles in shaping Middle East policy. Still other policy makers and implementers were Gerhard Weiss, who coordinated arms deliveries to Arab states and Palestinian guerrilla movements; Foreign Minister Otto Winzer, who cultivated bilateral relations with the Arab world; Peter Florin, the ambassador to the United Nations; Defence Minister Heinz Hoffmann, a central figure in the formation of military alliances with Arab countries like Syria and Iraq, and Erich Mielke, the director of the Ministry of State Security (Stasi), which maintained relations with Arab intelligence agencies and Palestinian movements.

Jewish communists who retained their positions of prominence in the regime, such as Albert Norden and Alexander Abusch, fully agreed with the regime’s shrill anti-Israel tone.

Herf argues that East Germany’s antagonism to Israel was diplomatically useful, a lever to break out of its global isolation. West Germany, under the Hallstein doctrine, refused to maintain formal relations with any nation outside the framework of the Warsaw Pact that established diplomatic ties with East Germany. The primary objective of East German diplomacy, therefore, was to shatter the Hallstein doctrine by forging relations with Arab states, which appreciated East Germany’s unabashed pro-Arab stance.

Iraq, in 1969, became the first country outside the Soviet bloc to form diplomatic relations with East Germany. Shortly afterward, Sudan, Syria, Egypt and South Yemen — all of which had signed trade agreements with East Germany in the mid-1950s — followed suit.

In 1965, the West German government established formal relations with Israel, prompting a majority of Arab states to sever diplomatic links with West Germany.

As Herf suggests, East Germany used the secret shipment of arms to Arab states as an enormously useful tactic to curry favor with the Arab world. During the Six Day War, East Germany delivered a huge cache of weapons — MIG-17 jet fighters, anti-tank rocket-propelled grenade launchers, armored cars, machine guns, assault rifles and anti-personnel mines — to its Arab allies at absolutely no cost.

Heinz Hoffmann — the East German defence minister who remained at his job from 1960 until his death in 1985, a period during which three Arab-Israeli wars erupted — played a pivotal role in shaping East Germany’s special bond with Syria. He forged a great working relationship, perhaps even a friendship, with his Syrian counterpart, General Mustafa Tlass, who held his post for 32 years. (In 1983, Tlass published The Matzo of Zion, an antisemitic screed that validated the Damascus blood libel accusation of 1840).

Hoffmann’s boss, Erich Honecker, supported Syria’s opposition to the 1978 Camp David Accords, branding them a “conspiracy of imperialism and Zionism.” The Syrian president, Hafez al-Assad, described Honecker as his “best friend.”

By Herf’s reckoning, East Germany’s arms deliveries to the Arab world began in 1965 with the shipment of weapons and munitions to Syria, Egypt, Iraq and Yemen. Separate arms shipments were sent to the Al-Saiqa Palestinian guerrilla group in Syria. In the wake of the Yom Kippur War, the East Germans delivered MIG jets, tanks, anti-tank rifles, artillery shells, grenades and land mines to Syria, with more than 1,000 East German military personnel accompanying the shipments.

From 1967 to 1989, East Germany provided Arab states and Palestinian armed organizations with 120 MiGs, 750,000 Kalashnikov assault rifles, 235,000 grenades, 25,000 rocket-propelled grenade launchers, 235,000 grenades, 180,000 anti-personnel land mines and 2.5 million cartridges. In addition, the East German government dispatched to their Arab allies binoculars, tents, parachutes, radios, field hospitals, chemical warfare equipment, sniper rifles, carbines, fuses and explosives.

And as Herf adds, East German technicians and trainers repaired and serviced 350 MIGs for the Syrian and Iraqi air forces and trained hundreds of Syrian, Iraqi, Egyptian, Jordanian, Lebanese, Moroccan and Palestinian military personnel.

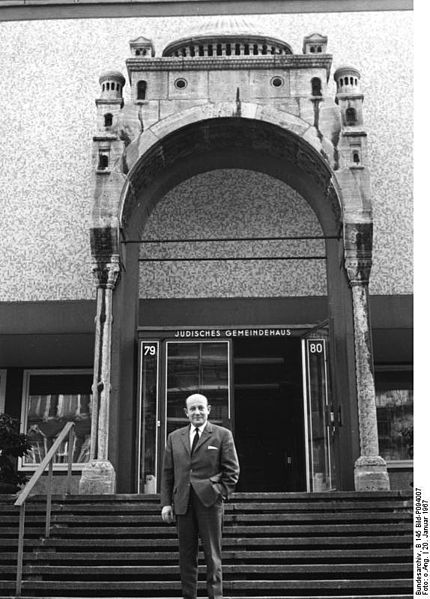

Like no other nation in the Warsaw Pact, East German leaders reached out to the Palestinians. In 1973, East Germany became the first country in the Soviet bloc to allow the PLO to open an office in its capital. This occurred after PLO delegations, led by Yasser Arafat, paid two official visits to East Berlin in that year. Heinz Galinski, a West German Jewish leader, condemned the visits in an open letter to Erich Honecker in Die Welt, a mass-circulation newspaper in West Germany. Galinki’s condemnation fell on deaf ears in East Berlin.

As a result of Arafat’s trips, the Palestinians received economic, military and medical assistance as well as diplomatic and media support. East Germany supported a motion granting the PLO observer status at the United Nations and called for the creation of the UN’s Committee for the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People. Unlike West Germany, East Germany voted for a resolution denouncing Zionism as a form of racism. East German newspapers, notably Neues Deutschland, compared Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon to the Nazis’ 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union and further claimed that Israel had adopted a policy of genocide toward the Palestinians and Lebanese civilians.

The West German far left was just as scathing. In Kiel, the Lebanon Action Group of the German Peace Society distributed a leaflet describing the Israeli invasion as “a war of extermination” against the Palestinians.

Herf concedes that East Germany paid occasional lip service to UN resolution 242, which, among other things, acknowledges the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every state in the Middle East. But in their public comments, he adds, East German diplomats never clearly stated that Israel had a legitimate right to exist.

East Germany only once publicly condemned a terrorist attack aimed at Israelis. The massacre of Israeli Olympic athletes in Munich in 1972 was condemned by an East German government broadcast as “a crime against the Olympic Games.” But tellingly enough, the broadcast glossed over the fact that the victims were Israeli Jews.

The reaction of West Germany’s far left fell short, too. In an essay written from her prison cell, Ulrike Meinhof of the Red Army Faction characterized the Palestinian attack as “simultaneously anti-imperialist and anti-fascist” and claimed that the attackers had shown “courage and strength.”

In the far left’s most overt demonstration of solidarity with the Palestinians, two members of the Revolutionary Cells, Wilfried Bose and Brigitte Kuhlmann, joined a team of hijackers from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine to hijack an Air France plane with 248 passengers on board. The plane was diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, where the two Germans were shot and killed by Israeli commandos.

With the collapse of Communist authority in East Germany in 1989, the new multi-party parliament tried to make amends. By a margin of 379 to 0, with 21 abstentions, the Volkskammer approved a resolution asking “the people of Israel for forgiveness for the hypocrisy and hostility of official (East German) policy toward the state of Israel …” The Volkskammer distanced East Germany from its legacy of anti-Israel polemics and envisaged diplomatic relations with Israel.

German reunification, which spelled finis to East Germany’s status as a separate state, was in retrospect a disaster for both Arabs and Palestinians. East German military cooperation agreements with Syria, Iraq and Libya ended abruptly and weapons deliveries to the Palestinians ceased immediately. In general, Herf says, the collapse of communist regimes in eastern and Central Europe was a catastrophe for secular Arab radicalism. As for the Palestinians, these events may have been one of the factors behind Arafat’s decision to recognize Israel under the 1993 Oslo accord.

In closing, Herf leaves absolutely no doubt where he stands.

His assessment is that East Germany and the far-left in West Germany bequeathed “a toxic ideological brew.” As he puts it, “Their distortions about the history of the state of Israel, their extensive use of terrorism, and their justifications for it have cast a long and destructive shadow over politics and political culture in the Middle East, in Germany, and around the world.”