Judging by Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry’s surprise visit to Israel a few days ago, Egypt has begun playing a more active diplomatic role in the virtually impossible quest to settle Israel’s perennial conflict with the Palestinians.

Shoukry, the first Egyptian foreign minister to set foot on Israeli soil in nine years, held intensive talks with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in Jerusalem on July 10.

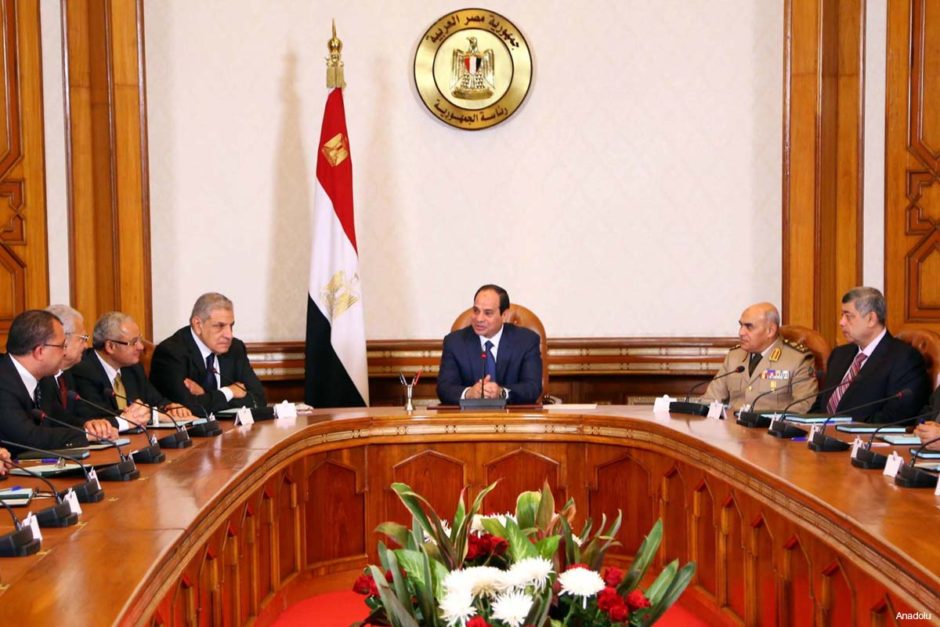

Shoukry’s whirlwind trip served Egypt’s interests, inasmuch as a breakthrough in the currently stalled peace process would bolster its status in the Middle East and improve the image of its authoritarian leader, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

Shoukry portrayed Egypt — — the first Arab country to sign a peace treaty with Israel — as a “steadfast” supporter of a two-state solution to untangle Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians. He added that Egypt stands ready to help facilitate this objective, which, he noted, could have “a far-reaching, dramatic and positive impact” on the region.

But, as Egypt knows full well, obstacles litter the path to peace.

On the eve of Shoukry’s visit, Egypt condemned Israeli plans to build 800 new homes in Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, annexed by Israel in 1967, and in the nearby Jewish settlement of Ma’ale Adumim, one of the largest in the West Bank.

The foundation for Shoukry’s visit was laid this past winter and spring.

On March 31, Shoukry met Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz in Washington D.C. to discuss regional issues, in the highest level meeting between Israeli and Egyptian cabinet ministers since the ouster of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in the winter of 2011.

Nearly two months later, Sisi claimed there is a “real opportunity” to end Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians.

He pointed out that its resolution could lead to warmer Egyptian relations with Israel, a point of immense interest to the Israeli government.

On June 4, Sisi addressed the Palestinian issue again, saying it has been neglected due to events in the region. He was presumably referring to the civil war in Syria, the chaos in Yemen and Libya and the rise of the jihadist Islamic State organization, which has imposed a reign of terror in Syria and Iraq and dispatched suicide bombers to Paris, Brussels, Ankara and Istanbul.

Sisi went on to say that the peace process should be revitalized. It has been languishing since the breakdown of U.S.-sponsored negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in the spring of 2014.

He made these comments shortly after France wrapped up a one-day summit in Paris to advance the prospects for peace. Its communique warned that continued Palestinian violence and Israeli settlement construction in the West Bank imperil the chances for peace.

Israel opposed the summit, claiming that only direct talks can bring a peaceful resolution of the conflict. Egypt supported it, having been one of the 28 nations that participated in it. Israel hopes that an Egyptian diplomatic push will render irrelevant France’s blueprint for peace, which may be adopted by the United Nations Security Council later this year.

Prior to the Paris conference, Netanyahu offered a regional approach to peacemaking. In a reference to the 2002 Arab League peace proposal, which calls for a complete Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank and the Golan Heights in exchange for a normalization of relations with a constellation of Arab states, he said: “The Arab peace initiative contains positive elements that could help revive constructive negotiations with the Palestinians.”

Netanyahu, however, insisted that Israel will not endorse the Arab plan unless it is significantly modified to “reflect dramatic changes in our region since 2002.”

He did not elaborate, but it’s clear what he wants. Netanyahu — a Zionist Revisionist — and his right-wing coalition government oppose a full Israeli pullout from the occupied territories, or the formation of a sovereign Palestinian state. They would prefer to grant the Palestinians limited autonomy under broad Israeli rule.

Netanyahu’s recalcitrance will probably scuttle Egypt’s considerations to warm up bilateral relations with Israel. This would not come as a surprise. Since the 1979 peace treaty was signed in Washington, Israel’s relationship with Egypt has been mercurial, due in large part to Israel’s refusal to withdraw from the West Bank and acquiesce to Palestinian statehood.

To put it another way, the gnawing Palestinian question has been a thorn in the side of Israel’s relations with Egypt, where support for the Palestinians is strong.

In protest over Israeli policies, Egypt has recalled its ambassador from Tel Aviv three times (1982, 2000 and 2012) and maintained what can only be described as a “cold peace” with Israel.

Egypt’s bilateral relations with Israel have been on a roller coaster ride since Mubarak’s overthrow by the army. In the aftermath of his ouster, Egypt was ruled by a council of generals led by Field Marshal Mohammed Hussein Tantawi, who had an ambivalent attitude toward Israel. Tantawi upheld Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel, but when mobs attacked the Israeli embassy in Cairo in September 2011, the police did not intervene.

Mohammed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president and a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, was ideologically hostile to Israel, yet he maintained ties with Israel and expressed support for the peace treaty. During the 2012 cross-border Gaza war, he dispatched his prime minister to Gaza in a show of support for the Palestinians, yet he was instrumental in arranging a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas.

Even as these events unfolded, Israel and Egypt — which have fought four wars since 1948 — upgraded the level of their mutual cooperation in the realm of security and intelligence sharing.

Israel and Egypt have common enemies — Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamic State, whose affiliate, Sinai Province, is deeply entrenched in the Sinai Peninsula. Since Sisi deposed Morsi in the summer of 2013, Israel has emerged as Egypt’s discreet ally in the struggle against terrorism and radical Islam.

“Sisi understood quickly that we are all in the same boat,” Israel’s ambassador to Egypt, Haim Koren, told the Associated Press earlier this month.

Overlooking provisions in its peace treaty with Egypt, Israel has allowed Egypt to move heavy military equipment into the Sinai, which, since Morsi’s fall, has been the scene of numerous Sinai Province attacks against Egyptian army patrols, bases and administrative offices.

Egypt’s new ambassador to Israel, Hazem Khairat, arrived in Tel Aviv this past January to take up his position. Egypt’s previous envoy, Atef Salem, was called back to Cairo shortly after Israel’s military campaign in Gaza in November 2012.

In April, in another sign of their convergence of interests, Egypt notified Israel of its intention to transfer control of two Gulf of Aqaba islands, Tiran and Sanafir, to Saudi Arabia, Israel’s undeclared ally. Israel briefly occupied these islands in the wake of the Six Day War.

Despite these developments, Egypt’s elite — politicians, civil servants, clerics, intellectuals and trade unionists — reject full normalization with Israel unless the Palestinian question is settled once and for all.

Several months ago, Tawfik Okasha, a member of parliament and a popular talk show host, was severely criticized after having dinner at the Israeli embassy with Israel’s ambassador. After more than two-thirds of his fellow parliamentarians voted to expel him, Okasha voiced regret for accepting the invitation.

“Our aspiration is to come closer to the Egyptian people,” Koren told AP in an indirect reference to that revealing incident. “But we understand it’s a long process, there’s a long way to go.”

Precisely.

At this moment in time, when the Middle East is in such turmoil, Israel and Egypt have good reason to be strategic partners, but the majority of Egyptians remain ill-disposed toward the Jewish state.

Egypt will not fully normalize relations with Israel unless the Palestinian problem is defused. Until then, the best Israel can hope for is security/intelligence cooperation with Egypt.