Most people do not realize that Christians, for centuries following the introduction of Islam in the Middle East, still constituted the majority of the population. From Greece to Egypt, this was the eastern half of Christendom.

When the first Islamic armies arrived from the Arabian Peninsula during the seventh century, the Assyrian Church of the East was sending missionaries to China, India and Mongolia. The shift from Christianity to Islam happened gradually.

But today, repression and religious cleansing is taking place in the Middle East. Entire communities have been uprooted, many fleeing for their lives, in Iraq, Syria and elsewhere.

The percentage of Christians in the region has dropped precipitously, as fanatical forces such as the Islamic State, Al-Qaeda, and others, seeking to recreate the expansionist Islamic empires of the past, make it clear that for them, all Christians are enemies.

From 1910 to now, the percentage of the Middle Eastern population that is Christian has declined from 14 percent to just four percent. This is large-scale ethnic cleansing, often ignored by the West.

The Aid to the Church in Need, a papal charity, last year described the current level of persecution against Christians as being “worse than at any time in history.” The report “Persecuted and Forgotten?” examined the plight of Christians in 13 countries over the past 12 years and found the number of Christians in the Middle East had dropped drastically.

In Syria, it fell to just 500,000 from about 1.5 million when the Syrian civil war began, driven out by extremist groups like the Nusra Front and Islamic State.

With the fall of Saddam Hussein, Christians began to leave Iraq in large numbers, and the population shrank to less than 500,000 today from as many as 1.5 million in 2003.

The Copts of Egypt are over 10 million strong and have lived in the country as Christians for two millennia. They are the largest Christian and largest non-Muslim community in the Middle East.

The history of Egyptian Christianity predates that of Islam. Coptic Orthodox Christianity started in the first century when the first church was established in the city of Alexandria. By the fourth century, Alexandria and its popes had emerged as one of the leading pillars of Christendom.

After the seventh century Islamic conquest, however, Egypt was Islamized and Arabized and Arabic gradually replaced the Coptic language. Slowly the country lost its Christian majority as Copts converted to Islam.

In the eleventh century, Pope Christodolos was forced to move the seat of the papacy to Cairo, which had eclipsed Alexandria as Egypt’s largest city.

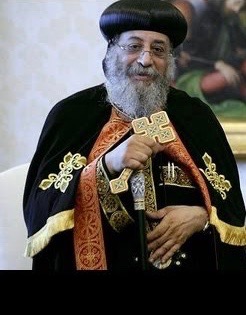

The Coptic Orthodox Church of Egypt is today led by Pope Tawadros II, who was elected in November 2012. The 118th Coptic pope, he succeeded the late Pope Shenouda III.

Egyptians who have remained Christians today consider themselves the original Egyptians with Pharaonic origin. Thus some Coptic intellectuals argue that Coptic culture is largely derived from pre-Christian culture, and precedes not just Islam but Christianity as well. It gives the Copts a claim to a deep heritage in Egyptian history and culture.

Nonetheless, Christian religious symbols are a means of identity expression for Copts, and the cultural development that distinguishes them from Egyptian Muslims has constructed a Coptic ethnicity.

Some ethnic Copts participated in the Egyptian national movement for independence and occupied many influential positions in the late 19th century. Many became prominent in business. However, things took a turn for the worse after Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the monarchy ad established a socialist republic after 1952.

Copts were severely affected by Nasser’s nationalization policies, and his pan-Arab ideology undermined the Copts’ strong attachment to Egypt and their sense of identity as pre-Arab Egyptians. Discriminatory state policies and political violence have historically marginalized Copts, particularly in many cities of Upper Egypt and in the Nile Delta area.

In August 2013, following the army coup that unseated the Muslim Brotherhood government of Mohammed Morsi, there were widespread attacks on Coptic churches and institutions in Egypt, amid clashes between the military and Morsi supporters.

The violence unleashed on Egypt’s Christians, which in recent years has left hundreds dead, is just the tip of a much more troubling iceberg.

The average Copt suffers from systematic forms of persecution and institutionalized discrimination emanating from all levels and segments of society, including at all levels of education. Copts have not only been significantly underrepresented in politics but also have had limited opportunities for employment and promotions, compared to the Muslim majority.

Attempts to address this are usually met with denials by Egyptian media and government. Sometimes, Copts drawing attention to these injustices are portrayed as agitators out to tarnish Egypt’s image.

The 2014 Egyptian Constitution defines Islam as the state religion. While it is the duty of the state to protect the religious freedom of Copts in constructing and renovating church buildings, establishing churches has at times elicited violence against Copts in several towns in Upper Egypt.

All this provides the backdrop to the mission of Coptic Solidarity, an advocacy group located in the Washington DC region. It seek to increase awareness of the situation of Copts in Egypt and to solicit the support of international public opinion and policy makers.

I attended its ninth annual conference, held in Washington June 21-22, which addressed the theme of “Egypt’s Copts: Faces of Persecution,” and presented a paper on Nazi anti-Semitism.

I was on a panel with Edward Clancy, the New York-based Director of Outreach for Aid to the Church in Need, the papal-sponsored charity; and Father Philemon Patitsas, of the St. Katherine Greek Orthodox Church in Naples, Florida.

A host of other academics, social activists, and American and Canadian politicians and bureaucrats, addressed the meetings.

They featured six members of the U.S. Congress, Lord David Alton of the British House of Lords, and MP Garnett Genuis of the Canadian House of Commons, in addition to 28 guest speakers of various ethnic and religious backgrounds.

As well, two Hungarian officials, Dr. Laszlo Szabo, the Hungarian ambassador to the United States, and Tristan Azbej, Hungary’s Deputy State Secretary for Aiding Persecuted Christians, a government department now located within the Prime Minister’s office, provided views on how Christians in the Middle East might be helped.

The consensus that emerged from the conference is that the situation for Copts in Egypt is dire.

Raymond Ibrahim, author of The Sword and the Scimitar, maintained that the Egyptian government and media deny there is a problem. They insist Copts are considered part of the country’s social fabric and thus are not discriminated against because of their faith. So violence and terrorism directed at Copts are considered an “aberration.” The government, he suggested, engages in deception and denial, “because they don’t want the status quo shaken.”

In fact sometimes Copts acting in self-defence against mobs are portrayed as perpetrators rather than victims. And it is claimed they exaggerate their plight.

Dr. Robert Herman, Senior Advisor for Policy at Washington-based Freedom House, agreed.

Under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, in office since 2013, independent media have been shut down, and some 40,000 opponents of the regime languish in prison. All legal sources, states the constitution, must be based on Islamic sharia law.

The absence of accountability in government allows attacks against Copts and other marginalized minorities to happen with impunity. Islamist websites spew hate against Copts on a daily basis, while critics are repudiated and their statements are said to be “full of lies.” Copts now face “a shrinking of civic space,” said Herman. “A democratic political system is the best way to protect religious freedom” and defend society against “hatemongers,” he concluded.

Andrew Miller, deputy director for policy at the Washington-based Project on Middle East Democracy, went further, asserting that Sisi pretends to be a “savior” protecting Copts from extremists like Islamic State, in order to advance his standing on the international stage.

Coptic Solidarity President Dr. George Gurguis expanded on this point. Sisi’s “friendly” gestures towards Copts have remained just that, as his government continued its severe discriminatory treatment and failed to protect them, their churches, or their property from violence by fanatics. More importantly, attacks on the Copts have continued with a ferocity that exceeds those observed during former President Hosni Mubarak’s rule.

The Coptic Church itself, he stated, has been co-opted and remains under immense pressure. It is in no position to provide moral support for the Copts in their struggle for religious freedom and equal civil rights.

Representative Dave Trott, a Republican Congressman from Michigan, also criticized Sisi, who frequently says that all Egyptians are equal. “So why is it that there are no Copts in senior positions in the defense department, in the foreign ministry, in the intelligence department in the military. There are no Coptic governors and, most significantly, there are no Copts on the national soccer team. I think the bias and bigotry continues and we have more to do.”

Republican Congressman French Hill of Arkansas, who in 2017 introduced Resolution 673 in the House of Representatives, expressing concern over attacks on Coptic Christians in Egypt, was the recipient of Coptic Solidarity’s annual leadership award.

“I’ll continue to get engaged with the U.S. government, our partners and other governments and those groups like Coptic Solidarity that continue to speak out against the plight of intolerance and fear that many Christians around the world face on a daily basis,” he indicated to those attending. “I’m honored to champion the issue on behalf of Coptic Christians in Egypt.”

Toronto-based Raheel Raza, President of Muslims Facing Tomorrow, addressed the problem of the large number of Coptic women and girls who are being kidnapped, forcibly converted and married to Muslims in Egypt. Often, she contended, Egyptian police and government officials are complicit, and kidnappers receive pay for each kidnapped woman.

One of the main organizations making life unbearable for Copts has been the Muslim Brotherhood, which, until 2011, was illegal under Egyptian law, as the state banned groups based on religion. But following the overthrow of Mubarak in February 2011, the Brotherhood-led Freedom and Justice Party won about half of the seats in parliamentary elections that took place later that year.

The group initially said it would not put forward a candidate for president, but eventually Morsi ran and in June 2012, became Egypt’s first democratically-elected president. However, he was deposed by the military after mass protests in July 2013 and a crackdown ensued. Hundreds of members were killed, and many more, including Morsi and most of the Brotherhood’s leadership, were imprisoned.

In September 2013, an Egyptian court banned the Brotherhood and its associations. Three months later the military-backed interim government declared the movement a terrorist group.

So Morsi’s election as president was the high point of their power. But they had prepared well for it, according to Raymond Stock, who teaches Arabic at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He lived in Cairo between 1990 and 2010 and has translated seven books by Egyptian Nobel literature laureate Naguib Mahfouz.

Stock, who was deported from Egypt by the Mubarak regime in December 2010 due to an article he published in Foreign Policy criticizing the government, told the conference that the 2011 “Arab Spring” that overthrew Mubarak has been misread.

While it was begun by liberal Egyptians using social media, he explained, it was the Muslim Brotherhood, through their mosques, who mobilized the thousands of people, congregating in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, who eventually made it a success. After a few days, asserted Stock, “they completely owned the movement.”

This is certainly a viewpoint that has rarely appeared in the mainstream media.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.