On December 11, a bomb ripped through the chapel in the St. Mark’s Cathedral complex, the seat of Egypt’s ancient Coptic Orthodox Church. It killed 27 people and wounded another 49, mostly women and children, and was one of the deadliest attacks on the country’s Christian minority in recent memory.

Responsibility for the attack was claimed by the Islamic State, though the Egyptian government blamed the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood.

Divisions have widened in recent decades between Egypt’s Sunni Muslim majority and the Coptic Christian minority, which accounts for about 10 percent of the country’s 92 million people.

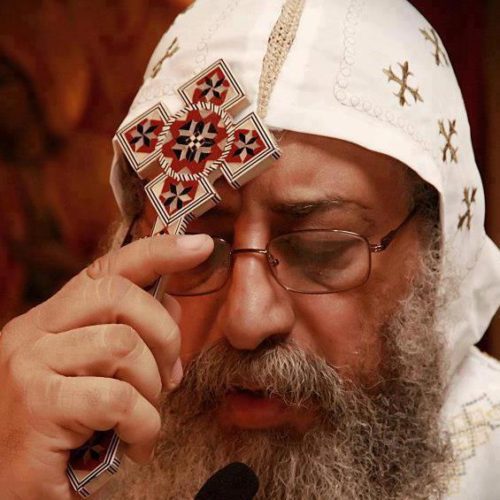

Pope Tawadros II, spiritual leader of Egypt’s Orthodox Christians, has said that attacks against Christians have occurred on average about once a month over the past three years. In too many instances, the police don’t even bother to investigate.

Egypt’s Christians have long complained of discrimination, saying they are denied top jobs in many fields, including academia and the security forces. And the Egyptian parliament in August passed a law imposing restrictions on the construction and renovation of churches.

The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights counted 77 incidents of sectarian violence between 2011 and 2016 in Minya governorate south of Cairo, home to Egypt’s largest Christian community. In May and again in July, hundreds of Muslims set fire to homes of Christians in the province.

The Islamic State group also has targeted Christians in the Sinai Peninsula, where jihadist radicals have established bases.

Egypt saw a previous wave of attacks by Islamic militants after July 2013, when the military under Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi overthrew President Mohamed Morsi, a freely elected leader and a senior Muslim Brotherhood official.

Many of his supporters blamed Christians for supporting his ouster, and scores of churches and other Christian-owned properties in southern Egypt were ransacked that year. The army and the police made little attempt to intervene.

Some 38 churches were looted and torched, while 23 others were attacked and heavily damaged in one week. According to the Coptic Orthodox and Catholic churches in Egypt, 160 Christian-owned buildings were also attacked.

Pope Tawadros, who was selected in November 2012, has visibly and vocally supported Sisi, seeing him as a welcome alternative to Morsi.

Two years earlier, a New Year’s Day 2011 bombing at the Saints Church in the Mediterranean city of Alexandria killed 21 people. That same year, 28 Christians were killed in clashes with the military outside the Egyptian Radio and Television Union (Maspero) building in Cairo. They were protesting against an attack on another church.

In 2006, there were days of clashes in Alexandria between Copts and Muslims after a Copt was stabbed to death during a knife attack on three churches.

Muslims and Christians were also involved in bloody inter-religious clashes in the town of el-Kosheh, south of Cairo, in 2000-2001.

An article by Alastair Hamilton, “Thirteenth-Century Muslim Anti-Christianity,” in the December 16, 2006 issue of the Times Literary Review documents Muslim attacks on Christians that go back many centuries.

Uthman ibn Ibrahim al-Nabulusi’s Sword of Ambition, dating from the mid-thirteenth century, is an example of one of many anti-Copt treatises that were composed in Egypt between the late twelfth and mid-fourteenth centuries.

Not only were the Copts naturally corrupt and dishonest, wrote the author of the document, but they were also prone to treachery, to informing Western Christians about the finances and military strength of the government, and “trying in every possible way to lure them to Egypt.”

Nonetheless, under the 19th-20th century monarchy, Copts were relatively secure. But they faced increasing marginalization after the 1952 coup d’état led by Gamal Abdel Nasser.

His pan-Arabist ideology had little room for a community that felt little connection to the larger Muslim Arab world. He also nationalized many businesses that were owned by Copts.

There are still some wealthy people in the Christian community. The entrepreneurs Nassef Sawiris, worth $5.2 billion, and his brother Naguib Sawiris, at $3 billion, are the two richest people in Egypt, according to Forbes magazine.

But as extremist strains of Islam gain growing support, for most Copts things seem to be getting worse. Increasingly, Egyptian Christians are speaking out against the government, ignoring the wishes of the church.

On September 19, during Sisi’s visit to New York to address the UN General Assembly, 82 Copts signed a public letter protesting the church’s widespread support of Sisi and expressed frustration that even under him, the situation for Christians in Egypt has not improved.

Some went so far as to say it is worse than under Hosni Mubarak, the dictator overthrown in February 2011 during the “Arab Spring.”

Two days earlier, in an interview with the Al-Masry Al-Youm newspaper, Tawadros had stated that media outlets were publishing false news about relations between Copts and Muslims.

“Egypt is not the best society in the world, but both its people and its leadership are trying to become the best society,” the pope explained.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.