Israel’s fifth war in 25 years is the subject of Uri Kaufman’s masterful book, Eighteen Days In October: The Yom Kippur War And How It Created The Modern Middle East, published by St. Martin’s Press.

Oddly enough, Kaufman is a real estate developer rather than a historian, but readers should not draw hasty and unwarranted conclusions regarding his expertise. Having worked on this volume for more than 20 years, he has produced a wide-ranging, erudite and lucidly-written volume viewed largely from Israel’s perspective and meant for laymen and experts alike.

Kaufman wades in slowly and methodically. He begins with the War of Attrition along the Suez Canal, which broke out almost immediately after the 1967 Six Day War. He then segues into the failed diplomatic efforts by Israel and Egypt to resolve their longstanding dispute.

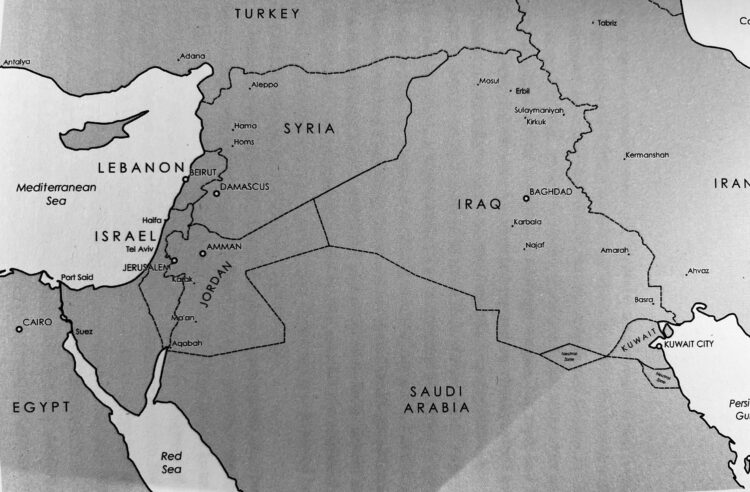

From this point forward, he focuses on Israel’s postwar complacency and on Egypt’s and Syria’s fierce determination to break the impasse by means of a coordinated offensive in the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights.

Having set the stage for a war whose political consequences would be momentous, he jumps into the armed conflict itself, which broke out on October 6, 1973 and ended 18 days later with a ceasefire on both fronts.

Finally, he tallies the results of the war, which cost Israel dearly in terms of casualties, but which was Israel’s last armed confrontation with Egypt.

In his survey of the War of Attrition, Kaufman discusses the important role of the Israeli Air Force in beating back Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s attempts to regain the Sinai, Israel’s deep-penetration air raids into Egypt, the Soviet Union’s military assistance to Egypt, and the dogfight on July 30, 1970 over the Sinai during which Israel shot down five MiGs piloted by Soviets.

During the course of this war, Israel lost 440 soldiers and some of its newly-delivered, U.S.-manufactured F-4 Phantom aircraft. Yet Egypt had achieved nothing tangible when an American brokered truce brought the fighting to a close on August 8, 1970, writes Kaufman.

Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, offered Israel a diplomatic solution in the winter of 1971. He demanded Israel’s full withdrawal from the Sinai and the rest of the occupied areas, plus a just settlement of the Palestinian refugee problem. Golda Meir, the Israeli prime minister, refused to pull back to the pre-1967 armistice lines, but Defence Minister Moshe Dayan raised the possibility of a withdrawal some 40 kilometers east of the canal to the Mitla and Gidi passes.

As diplomacy waxed and waned, Israel dug in, building a string of fortifications along the length of the canal. Named after General Chaim Bar-Lev, the Israeli chief of staff, and known as the Bar-Lev Line, it was sparsely manned. As Kaufman notes, it was never intended to stop an invading Egyptian force. Deployed as a tripwire, its purpose was to activate an Israeli counter-attack spearheaded by the air force and several hundred tanks stationed 15 kilometers behind the canal.

Disagreement among Israeli generals raged over Bar-Lev’s strategy, but in the fashion of the day they believed that the Egyptians were incapable of crossing the canal and seizing the Bar-Lev Line. As Dayan boasted, “The Arabs know that if they attack us, they will be wiped out.”

Suffering from hubris, Dayan and his colleagues were certain that, if all else failed, the air force would obliterate an Egyptian invasion force. Israel, too, underestimated Sadat as a resolute leader.

In 1972, David Elazar replaced Bar-Lev as chief of staff, while Eli Zeira was named head of Israeli military intelligence. Zeira believed that Israel could win victories over the Arabs with ease. In Egypt, General Ahmed Ismail Ali was appointed minister of war and General Sa’ad Shazly was placed in charge of devising a plan to destroy the Bar-Lev Line and recapture the Sinai up to the Gidi and Mitla passes.

From 1969 onwards, Israel was privy to top secret information from Egypt supplied by Ashraf Marwan, a flashy, high-living Egyptian married to Nasser’s daughter. When Sadat assumed the presidency after Nasser’s death in 1970, he appointed Marwan as one of his chief aides. No one really knows why Marwan spied for Israel, but he was probably not a double agent and Israel paid him handsomely for his betrayal.

On the basis of his invaluable data, Israeli military planners coined a new Hebrew word, “conceptzia,” to describe Israel’s strategic approach toward Egypt and Syria, its most formidable foes. First, Syria would not wage war without Egypt. Second, Egypt would not engage Israel in a war unless it could neutralize its air force. As Kaufman observes, the first part of the “concept” proved true, but not the second.

Egypt’s constant military exercises along the border, numbering no less than 22 in 1973 alone, made it all the more difficult for Israel to predict if an actual war was imminent.

On August 21 of that fateful year, Egypt and Syria finalized plans to attack Israel on two fronts. Eight days later, Sadat and Syrian President Hafez al-Assad chose a date, October 6, which fell on Yom Kippur, the holiest Jewish month. The offensives were dubbed Operation Badr.

Egypt had 1.2 million soldiers at its disposal, plus 420 fighter jets, 1,880 tanks, 2,400 artillery pieces and 50 surface-to-air missiles batteries. Syria would field 185,000 troops, 326 combat jets and 1,170 tanks.

Against this Israel could muster a regular army of 950,000 enlisted soldiers and reservists, 3,500 tanks, 680 aircraft and 1,700 artillery pieces. When the war broke out, Israel had 300 and 175 tanks respectively on the Egyptian and Syrian fronts.

On September 25, King Hussein of Jordan secretly flew to Tel Aviv to inform Meir that the region was on the brink of war. He was returning a favor. Three years earlier, Israel had averted a Syrian invasion of northern Jordan.

When Zeira learned from Marwan on October 2 that war was imminent, he kept this information to himself and did not notify either Elazar or Meir. In a disastrous miscalculation, he assumed that the latest Egyptian military exercises were not a prelude to war and that the cherished “concept” would hold up.

On October 4, Marwan reported that a war would break out in just a matter of hours. He conveyed that alarming news to the director of the Mossad in an urgent meeting in London.

Now convinced that Israel was on the cusp of a war, Dayan ordered a partial mobilization of 60,000 soldiers, enough to defend the borders. Elazar wanted to mobilize 120,000 troops not just for defence but for a counter-attack, but Dayan demurred.

Thinking that Israel should launch a preemptive air strike of the kind that brought it immediate victory in the Six Day War, Elazar ordered the commander of the air force, Benny Peled, to draw up plans for a strike on Egyptian and Syrian surface-to-air missiles. Meir rejected his suggestion after U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger warned the Israeli ambassador in Washington that there must not be preemptive air raids.

In the first five minutes of the war, Syria let loose with an artillery barrage of 25,000 shells. Assad hoped that Syria could recapture the Golan within two days and reach the Jordan River before Israeli reservists made it to the front lines. Syria threw 500 tanks into its opening assault. By the end of the war, two-thirds of the Syrian tank force had been decimated.

During the opening hours of the war, Syria recaptured an unfortified Israeli base on the lower ridge of Mount Hermon, which offered Israel grand views of Damascus. Israel would later retake Mount Hermon.

In Kaufman’s appraisal, Israel initially fared badly in defending the Golan, but “the Syrians fared only marginally better attacking it.” While Syria’s offensive in the north and the center basically faltered, the Syrians succeeded in breaking through in the south. In a massive tank battle in the Valley of the Tears, Israel finally pushed back Syria and regained the momentum.

Iraq joined the war after desperate Syrian entreaties. Its expeditionary forces of 60,000 troops, 700 tanks and hundreds of vehicles rolled into Syria undisturbed despite warnings by Israeli military intelligence. Kaufman argues that Israel’s failure to intercept the exposed Iraqi column was a monumental failure. In his opinion, the Iraqis contributed little of value to Syria’s war effort.

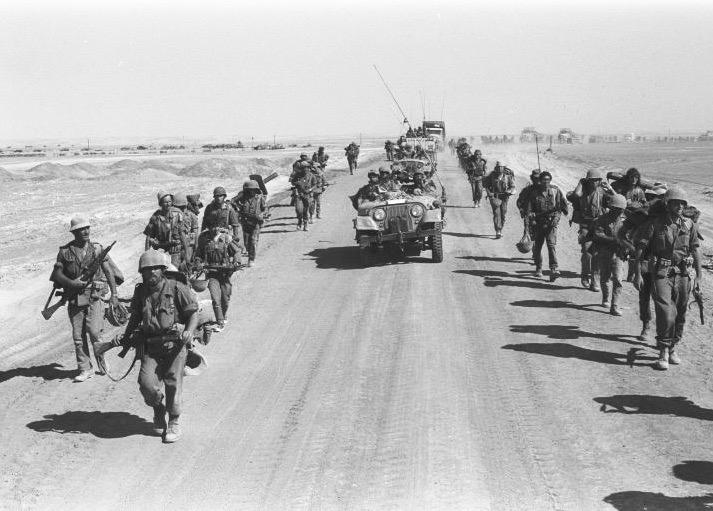

Back on the Sinai front, thousands of Egyptian commandos crossed the canal and seized the Bar-Lev Line, losing 280 soldiers in the process, far less than Egypt’s high command had expected. By the next day, 1,020 Egyptian tanks were on the east bank of the canal.

These setbacks brought Dayan to despair. Fearing that Israel, the Third Temple, was imperilled, he sought authorization to begin preparations for a “display” of Israel’s nuclear might. Meir, badly shaken, contemplated suicide. The momentary panic that gripped the pair did not affect Elazar, who maintained his cool under crushing pressure.

After one of the most respected army officers told Dayan that the battle for the Golan was lost, Israel attacked Syria’s surface-to-air missiles. Six Israeli aircraft were downed and ten others were damaged in Operation Dougman 5, which Kaufman claims was “the biggest disaster in the history of the Israeli Air Force.”

Subsequently, however, Israeli jets bombed Syrian military headquarters in central Damascus as well as infrastructure facilities such as oil refineries and electric plants throughout the country. Israeli ships bombarded Syria’s main navy base in Latakia in what became the first naval engagement fought exclusively with missiles.

With Israel losing ground in the north, Dayan transferred an entire division along the Jordanian border to the Golan, leaving the border with Jordan essentially undefended. Having learned a bitter lesson in the Six Day War, King Hussein of Jordan had no desire to become involved in the war, but under unrelenting pressure, he dispatched a token armored force of 160 tanks and 40 artillery pieces to Syria on October 13.

Egypt’s offensive in the Sinai proved so successful in the first few days that Dayan suggested a withdrawal to the Gidi and Mitla passes. Its success was due, in part, to the effectiveness of two Egyptian weapon systems the Soviet Union had supplied. Egypt’s arsenal of RPG-7 and Sagger missiles destroyed 42 percent of Israeli tanks, prompting Dayan to say, “I did not properly assess the strength of the enemy, plus I exaggerated our ability to withstand them.”

On October 8, an Israeli tank column commanded by Asaf Yaguri attacked Egyptian positions along the Bar-Lev Line in an attempt to turn the tide. It was a suicidal mission. Yaguri’s force was virtually wiped out by Saggers. Israeli air strikes on Egyptian bridges thrown across the canal failed. “October 8 would be remembered as the darkest day in the history of the Israeli army,” writes Kaufman.

Yaguri, a lieutenant-colonel, was wounded and captured, becoming. the highest-ranking Israeli officer to fall into enemy hands. In all, 248 Israeli soldiers were captured by Egypt. Sixty six Israelis fell into Syrian captivity.

Ariel Sharon, an Israeli general serving in the Sinai, was not disheartened by these failures. He called for a counter-strike across the canal and into the Egyptian heartland. Sharon’s commando force stormed into Africa in a prelude to Israel’s invasion of western Egypt, which led to bitter wrangling among Israeli generals and the replacement of Shmuel Gonen as the Israeli general in charge of the southern front.

Once in Africa, Israel engaged Egypt in the fierce Battle of Chinese Farms, which exacted a heavy toll on both sides in terms of men and materiel. An Israeli soldier who participated in this confrontation saw Egyptians going from tank to tank shooting Israeli survivors.

In mid-October, Shazly was ordered by his superiors to launch an offensive with 330 tanks with the aim of reaching the two passes. It was a turkey shoot as far as Israel was concerned. Egypt lost 250 tanks in a single day, but even after this disaster Egypt still possessed about 720 tanks east of the canal.

On October 9, U.S. President Richard Nixon formally agreed to replenish all of Israel’s tank and fighter jet losses. Kissinger told the Israeli ambassador, Smicha Dinitz, that Israel could count on the United States. “As long as I am here, I won’t abandon Israel,” he said.

The massive airlift which resupplied Israel did not take place until the middle of the month, but on October 19, Nixon asked Congress for a $2.2 billion aid package for Israel. Amid these developments, Saudi Arabia announced a total embargo on oil exports to the United States.

By this point, Israel was ready for a ceasefire, as Kissinger learned from Dinitz. Sadat rejected the proposal, but on the following day, October 13, he responded with a list of demands requiring Israel to withdraw behind the pre-1967 lines and acquiesce to Palestinian statehood. In exchange, Sadat was prepared to offer a vague statement of non-belligerency. To Israel, Sadat’s proposal was a non-starter.

Sadat, having been hailed as “the hero of the crossing” by the state-owned Egyptian media, was ready to wage a war of attrition against Israeli forces, but he had second thoughts when he discovered to his horror that the Israelis had sent a large force into Egypt and surrounded the Third Army.

The possibility that Israel might destroy it alarmed the Soviet Union, Egypt’s arms supplier and political patron, and set off fears in Washington that the Soviets might interfere militarily.

On October 22, with the war drawing to a close, the Israeli Air Force launched its final mission against Egypt’s surface-to-air missile batteries along the canal. “With that, Egypt’s air defence system essentially ceased to exist,” says Kaufman, implying that Israel regained its much-vaunted air superiority.

With little planning, Israel attacked Suez, but the gamble failed. Israel fell into an Egyptian trap and barely extricated itself from the city, all the while losing 80 soldiers in the futile operation.

Having agreed to a truce, Sadat convinced Assad to go along, but Syria left the door open to further hostilities. In the subsequent war of attrition on the Golan, during which both sides engaged in artillery duels, 442 Israeli troops were killed. Syrian losses are unknown.

The Yom Kippur War was extremely costly for Israel. The Israeli death toll was 2,222, with 7,251 wounded. Israel lost 98 fighter jets, two helicopters and 800 tanks, but captured upwards of 400 Soviet-built tanks, many in working order. In economic terms, the war cost Israel $7 billion, the equivalent of one year of gross domestic product.

Egypt and Syria lost 11,000 and 6,000 soldiers respectively. Kaufman estimates that 870 Palestinians in the Syrian armed forces were killed. He points out that Moscow quickly resupplied Egypt’s and Syria’s armed forces.

The war left a bitter taste in the mouths of many Israelis.

The postwar Agranat Commission absolved Meir and Dayan, but they were both forced to resign. The commission found that Zeira and Elazar had failed to carry out their duties. In Kaufman’s opinion, Elazar acquitted himself remarkably well, and the critique of his performance was nothing less than slanderous.

Sharon emerged from the war smelling of roses, and he went on to forge a career in politics as a minister and as prime minister.

Kaufman claims that Israel won the war, but this is debatable.

Israel pushed back the Syrians and penetrated Syrian territory, leaving Damascus within Israeli artillery range. The Syrians, though, were ready to fight a war of attrition after the formal end of hostilities.

In the Sinai, Israel failed to dislodge the Egyptian bridgehead along the canal. Israel, however, regained the initiative on the ground and in the air on both fronts toward the close of the war. Some, then, might argue that the war ended on a somewhat inconclusive note.

Politically, the war nudged Egypt out of the Soviet orbit and into the U.S. sphere of influence. Syria remained a Soviet client state. Thanks to Kissinger, Israel and Egypt signed two disengagement agreements that led to Israeli withdrawals from the Sinai. Kissinger was also instrumental in brokering a disengagement pact between Israel and Syria.

Egypt, in 1979, signed a peace treaty with Israel. Israel tried several times to reach a rapprochement with Syria, but fell short of the mark. Jordan and Israel made peace in 1994.

Absent these treaties, the 2020 Abraham Accords might never have seen the light of day.

The Yom Kippur War cost both sides dearly in blood and treasure, but it produced a significant political realignment in the Middle East and ended Egypt’s military involvement in the Arab-Israeli conflict.