It should come as no surprise that food has a central place in the annals of Zionism. Israel, after all, has been referred to as the Land of Milk and Honey.

As Yael Raviv writes in Falafel Nation: Cuisine and the Making of National Identity in Israel (University of Nebraska Press), “Food has been used as a marketing tool for the land of Israel since ancient times.”

In this informative and intriguing work, which mainly focuses on the period between the Second Aliyah in 1905 and the Six Day War in 1967, Raviv convincingly argues that the Zionist movement employed food motifs and its achievements in agriculture as instruments in the construction of a Jewish nation in Palestine.

Food, like excavated Jewish archeological artifacts, was a means by which Jews could personally reconnect with the land, says Raviv, an adjunct professor in the Department of Nutrition, Food Studies and Public Health at New York University.

“Foodstuffs of biblical origin, like wheat, dates and olives, were presented on Zionist commemorative postcards and on fund-raising posters. Export products such as grapes, wine, olives, olive oil, figs, dates and pomegranates ‘sold’ Zionist ideology abroad. These foods, as well as agricultural tools that can be traced back to biblical times, evoke a sense of historical continuity and enforce the claim of an inherent bond between the Jewish people and their ancient land — a necessary condition for Jewish nationhood.”

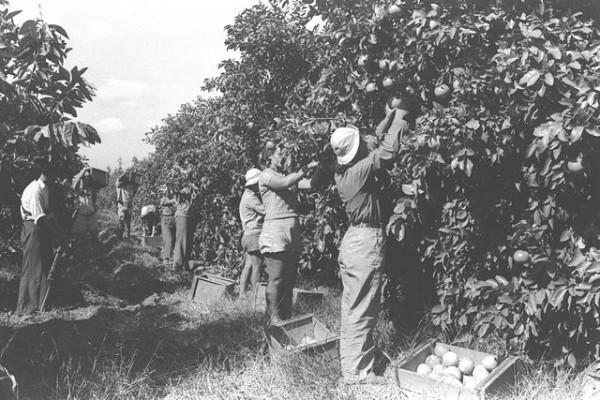

During the first decades of the 20th century, Jewish farmers on kibbutzim and moshavim cultivated grapes and olives, both of which supported the Zionist narrative that a direct line could be traced from the Israelites to modern Israel.

Oranges, in the late 1920s, replaced olives and grapes as the Yishuv’s chief agricultural product. Although oranges had no connection to the Bible, they were ideally suited to Palestine’s climate and soil conditions.

“Oranges became identified with the Zionist project, and the Israeli state embraced the orange as quintessentially Israeli,” writes Raviv. “The orange indicated certain characteristics that the state wished to promote as part of its image, such as self-sufficiency and rootedness in the land.”

Once the Jewish leadership realized that food in all its glorious manifestations could be a transmitter of Zionist values, cookbooks soon appeared. In 1935, Dr. Erna Meyer published the first cookbook written for a Jewish readership, How to Cook in Palestine? Urging housewives to incorporate local produce into their meal planning, Meyer wrote, “This is one of the most important means to establishing our roots in our old-new homeland.”

In one of her most instructive chapters, Raviv explains how falafel — a pita bread sandwich stuffed with deep fried chickpea balls, garnished with diced vegetables and slathered with piquant sauces — morphed into a vibrant symbol of Zionism.

Originating in Arab kitchens, falafel was an instant hit. By the 1920s, it had become an iconic street snack in the Jewish community, with the majority of falafel stands being run by Jews from Yemen.

In 1949, following the War of Independence, the Israeli government introduced food rationing, restricting the sale of meat and encouraging the consumption of local products for the next decade. The falafel, regarded as an affordable and flavourful source of protein, became even more popular as a fast food.

“By the late 1960s, falafel had become ‘nationalized’ into Israeli culture and cuisine,” says Raviv. “Falafel had an advantage in its status as a pareve food (neither meat nor dairy), which gave it flexibility in kosher menus.”

The Israeli folk song, a vehicle for instilling nationalist values, tapped into themes relating to food and agriculture. One of Israel’s foremost poets, Haim Nahman Bialik, wrote a song, In the Garden, which expressed this sentiment: In the garden plot/right around the barrel/cabbage and cauliflower/joined in a dance.

In elementary schools, Raviv notes, vegetable gardening was on the curriculum. “It was seen as a first step to getting young children closer to the land and instilling in them respect for and love of agricultural labor. It is important to note that this was a common practice in urban schools, as well as in rural ones.”

As she also points out, food played a vital role in the acculturation and integration of new immigrants.

By her reckoning, “the growing prestige and professionalism of cooking in Israel during the 1960s was closely tied to the development of the tourist industry.”

The sumptuous Israeli breakfast buffet, which reached its apotheosis in reputable hotels, was an integral component of advertising campaigns promoting tourism. “Whether tourists were visiting a kibbutz or a big city, they knew breakfast would be reliably delicious,” she observes.

Since the 1990s, she adds, the restaurant scene in Israel has blossomed, having been internalized into the Israeli experience. Top-ranked Israeli chefs go out of their way to tout the flavour and freshness of Israeli vegetables, fruits, cheeses and baked goods.

Raviv, in the final pages of Falafel Nation, offers readers a pastiche of gastronomic nuggets.

She recalls the everyday snacks that have nurtured innumerable Israelis — lemon-flavoured popsicles, which inspired the Israeli cult film Eskimo Limon; Bamba, a puffed peanut treat, and Crembo, a chocolate-covered fluffy egg-white cream bar.

She reminisces about the kumsitz, the quintessential Israeli bonfire gathering during which participants consumed snacks, drank coffee, told stories and sang patriotic songs.

In closing, she writes, “In recent years, food has enjoyed a constantly rising status and increased prominence in Israeli society. The abundance of quality restaurants, the vast selection of exotic ingredients, and the proliferation of cooking shows on television reflect the growing interest in cooking and eating and the growing knowledge and sophistication of the Israeli consumer.”