As Netflix began streaming Farha, a restrained Palestinian feature film that presents the Nakba in microcosm, the United Nations General Assembly voted to adopt a resolution to commemorate the seventy fifth anniversary of this event come next May.

The resolution, sponsored by Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, Yemen, the Palestinian Authority and Senegal, was passed on December 1 by 90 countries. Thirty, including Israel, the United States, Canada, Britain and Germany, voted against it. Forty seven abstained.

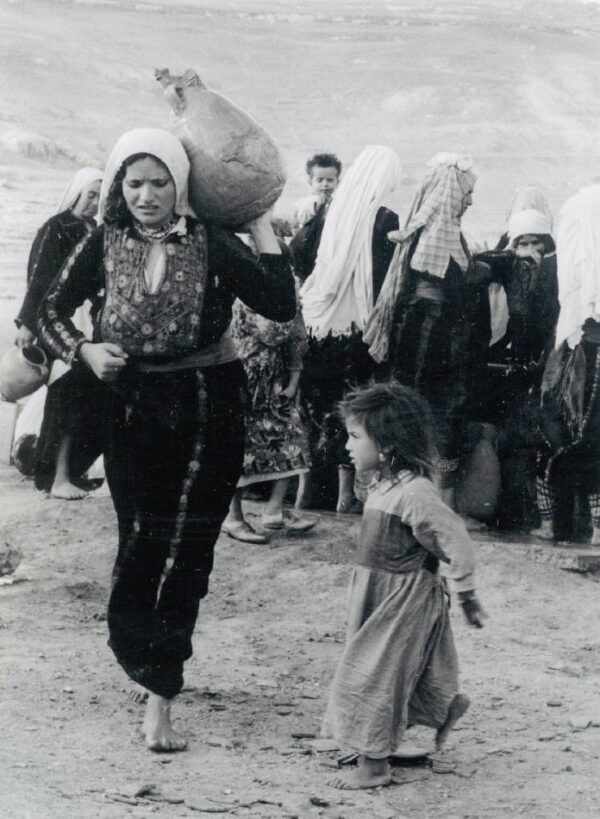

More than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs inside Israel were displaced and dispossessed during the Nakba, the Arab word for catastrophe. It took place in 1948 as the first Arab-Israeli war raged.

The Nakba exacted a toll on the family of the director of Farha, Darin Sallam, a Palestinian from Jordan. Farha, inspired by this gigantic upheaval which scattered Palestinians to neighboring Arab lands, unfolds early in a war that pitted Israel against local Palestinian fighters and five Arab armies.

To this day, the Nakba is burned into the soul of Palestinians, and it is one of the key issues that will have to be settled should Israel and the Palestinians ever decide to negotiate an end to their bitter conflict.

Israelis, in general, are ambivalent about the Nakba.

On the one hand, they argue that the Palestinians were the authors of their own misfortune, having rejected a 1947 United Nations partition plan that recommended the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. On the other hand, they realize that the Nakba painfully uprooted families from their homes, properties and native land.

Still other Israelis, usually from the right-wing camp, have turned a blind eye to the Nakba. On the eve of Farha‘s debut on Netflix, two Israeli cabinet ministers condemned the streaming platform for agreeing to screen it. Finance Minister Avigdor Liberman charged that Farha distorts reality and incites against Israeli soldiers. Culture Minister Chili Tropper claimed it is filled with “lies and libels.”

Sallam, of course, views the Nakba from purely a Palestinian perspective, which is to be expected.

It begins with a pastoral shot of Palestinian girls in a lush orchard and with British forces hastily leaving Palestine following the dissolution of Britain’s League of Nations mandate.

Farha (Karam Taher), a 14-year-old intellectually inclined Palestinian girl, is the central character. Taher portrays her in a convincing performance. A resident of a dusty village, Farha is feisty, studious and addicted to reading. She wants to continue her education in the city and aspires to be a teacher.

Her father (Ashraf Barhom), the village mayor, is less than keen about her plan. A traditionalist, he thinks she should get married when she is of age. He changes his mind when one of his relatives, an enlightened relative, convinces him that Farha will be much better off as an educated woman.

Farha’s hopes and dreams vanish when Israeli troops conquer her village. Her father arranges for a taxi to drive her to safety, but she insists on remaining behind with him. Amid the sound of gunfire, he locks Farha in a shed and promises to return soon.

As she patiently waits for him, she hears soldiers urging villagers to leave. From a peephole, she watches an officer interrogating a local Palestinian man about hidden weapons. A Palestinian collaborator with a hood over his face claims the villagers are not fighters and should be left alone.

In the most graphic scene, an Israeli officer orders a soldier wearing a yarmulke to kill a newborn Arab infant.

Eventually, Farha breaks out of the shed, only to discover an atrocity. Her father never shows up, prompting Farha to walk away from the village.

The few Israelis that appear in this clearly pro-Palestinian film are almost monosyllabic, remain nameless, and are portrayed mostly unsympathetically. Sallam leaves a viewer with the distinct impression that the Nakba was caused solely by Israel’s cold-hearted decision to drive out the Palestinians, but the truth is far more complex and nuanced.

As reliably documented, there were times, such as in Lod and Ramle, when Israel forced Palestinians from their homes. In other instances, they left voluntarily, believing they would soon one back. In Haifa, however, the Jewish mayor asked Palestinian Arabs to stay.

Sallam is not interested in such nuances, preferring to adhere to the time-honored Palestinian ideological narrative that every Palestinian person who departed was expelled.

In terms of production values, Farha is reasonably competent and in tone it is bereft of false drama or histrionics. But in the final analysis, it is a one-sided film that depicts Palestinian suffering and perpetuates the cherished myth that all Palestinians were expelled by Israel.