The rise and fall of totalitarianism in Italy is spelled out in elaborate detail in Fascism in Colour, now available on the Netflix streaming channel. Produced and directed by Chris Oxley, this two-part film charts Benito Mussolini’s path from fiery socialist to arch nationalist.

Mussolini, the world’s first fascist dictator, turned his back on socialism after Italy’s disastrous defeat at the battle of Caporetto in World War I. The fascist movement he and his associates founded in 1919 capitalized on two issues — the disillusionment with the outcome of the war and the fear that bolshevism might triumph in Italy.

Fascism in Colour unfolds through file footage, reenactments and interviews with historians such as Stanley Payne and Alexander Stille.

Fascism, Italian style, appealed to war veterans, the middle-class and some peasants. It also captivated, interestingly enough, assimilated conservative Jews like Ettore Ovazza, a patriotic banker from Turin who had fought in the war. In its formative phase, Italian fascism was not antisemitic and rejected Nazi racial theories.

The Socialists emerged as Italy’s largest political party after the 1919 general election, but the fascists were determined to seize power, by force if necessary. By 1921, fascist party membership had ballooned to more than 200,000. Among its new recruits were industrial workers and students, not to mention police and army officers.

After seizing control of various provinces by means of violence, the fascists staged a mass march on Rome in 1922. Brazenly enough, they demanded the reins of power. King Victor Emmanuel could have stopped them cold in their tracks, but instead, he invited Mussolini to form a coalition government.

The Italian monarchy was thus inadvertently responsible for paving the way for the fascist dictatorship. Mussolini grasped the opportunity, and in due course, he established a police state.

In the second segment, Oxley examines Mussolini’s campaign to consolidate his grip on a restive country and restore the glory of the Roman empire.

At Italian schools, teachers brainwashed students, convincing them that fascism and patriotism were inextricably intertwined. And in 1929, the fascist regime reached an historic rapprochement with the Vatican, prompting Pope Pius XI to declare that Mussolini was the manifestation of divine providence.

Initially, Mussolini regarded Adolf Hitler, Germany’s fascist chancellor, as a junior partner, and ridiculed Hitler’s anti-Jewish rantings. But Mussolini’s aggressive foreign policy, in Africa and Spain, drew Italy inexorably closer to Germany.

In 1938, without German prompting, Mussolini unveiled harsh antisemitic edicts. At first, Jewish fascists and war vets like Ovazza were exempted from its provisions, but they, too, were betrayed and eventually treated like second-class citizens. Indeed, Ovazza paid dearly for his illusions.

Claiming that Italy’s military alliance with Germany was ill-advised, the film documents catastrophic Italian battlefield defeats in Greece, Libya and the Soviet Union. They weakened Mussolini and persuaded his son-in-law, the foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano, that Italy had erred in aligning itself with Germany.

Ciano, in 1943, joined a group of disaffected fascists who toppled Mussolini. In quick succession, the new Italian government surrendered to the Allies and Germany invaded Italy, dooming its venerable Jewish community. Mussolini was arrested, but the Germans freed him in a rescue operation and installed him as the leader of the Salo Republic in northern Italy.

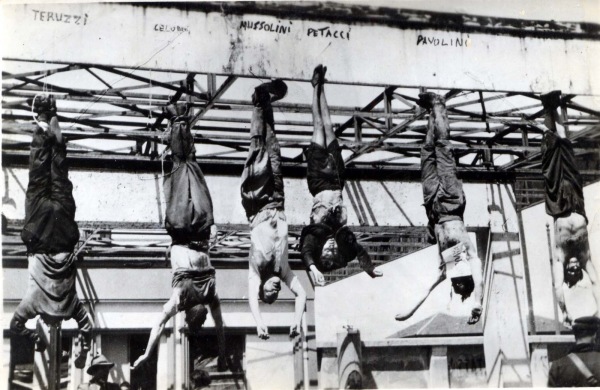

On April 27, 1945, a few days before the official end of the war in Europe, Mussolini and his mistress were caught by partisans, murdered and strung upside down on poles in a gruesome spectacle.

As the movie suggests, Mussolini lived and died by the sword.