Nearly 55 years after its inaugural opening at the Imperial Theatre in New York City, Fiddler on the Roof, the iconic Broadway play, is still going strong. Such is its longevity that it has been performed every day somewhere around the globe since September 22, 1964.

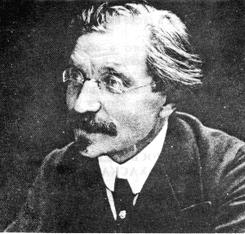

Based on the stories of Sholem Aleichem, this dark musical has been a critical and commercial success, despite the stunningly misguided appraisal of New York Times critic Walter Kerr, who condescendingly dismissed it as a “near miss.”

The first major musical on the U.S. stage to omit an American character, Fiddler on the Roof has indeed been enormously popular. For almost a decade, it held the record as the longest running musical on Broadway. As well, this mega hit won nine Tony Awards, spawned five Broadway revivals, and has been staged in countries ranging from Japan and Austria to South Africa and Mexico.

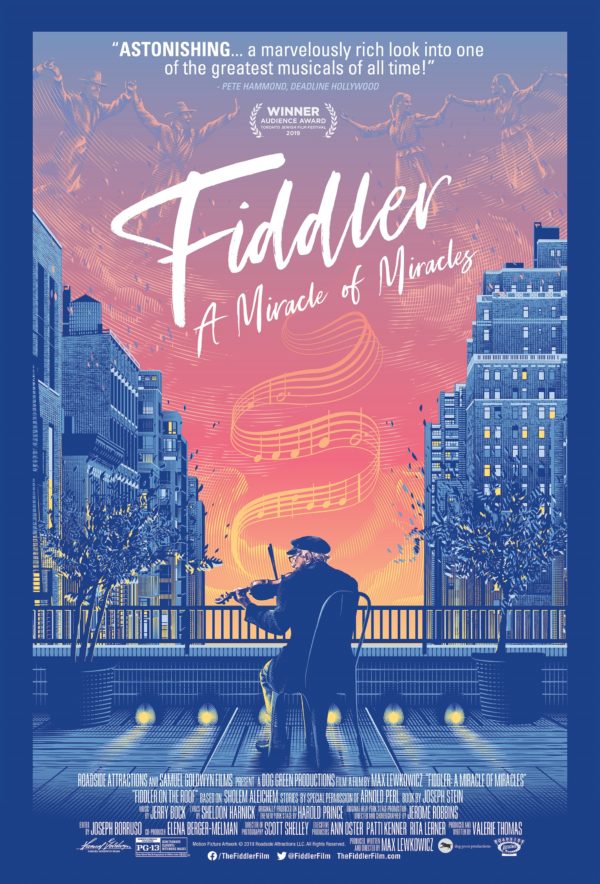

Turned into a Hollywood movie in 1971, it is the subject of Max Lewkowicz’s nostalgic film, Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles, which opens in Toronto on August 23.

Set in 1905 in czarist Russia’s Pale of Settlement, where most Russian Jews were forced to live under the weight of antisemitic restrictions, Fiddler on the Roof is about the allure of tradition and the pull of assimilation in the ramshackle shtetl of Anatevka. Tevye, a poor dairy farmer, lives there with his wife Golda and five unmarried daughters until a pogrom drives them out.

“The goal of our documentary,” says director Max Lewkowicz “is to understand why the story of Tevye the milkman is reborn again and again as beloved entertainment and a cultural touchstone the world over.”

In his quest to fulfill this goal, Lewkowicz interviews a host of personalities connected with the play, but the most important figures in his informative film are Sheldon Harnick, the lyricist, and Jerry Bock, the composer. Both were charmed by the ambience of Sholem Aleichem’s stories, originally written in Yiddish, and by the strength of his characters.

“They leaped off the pages,” recalls Harnick in awe.

The most difficult task facing Harnick was writing the segment where one of Tevye’s daughter, Chava, marries out of the faith and immigrates to the United States with her Russian husband. Tevye is heart-broken by Chava’s decision, but wishes her well in America.

Lewkowicz believes that Fiddler on the Roof, though particularistic in terms of its Jewish roots, carries a universal message, with themes ranging from tradition and bigotry to oppression and ethnic cleansing.

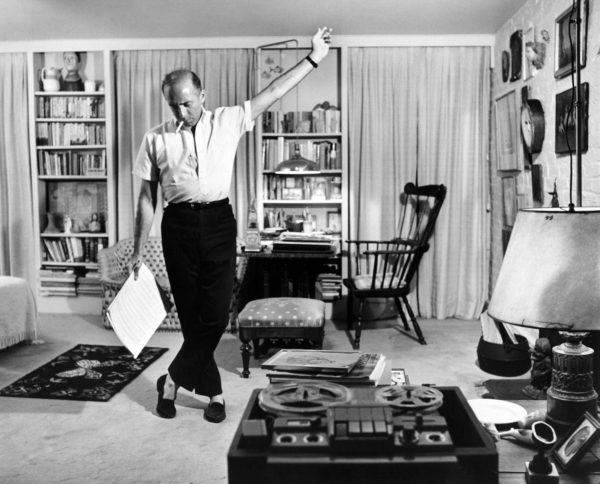

He leaves the impression that Jerome Robbins, the choreographer, had a powerful impact on the play. Conflicted by his Jewish identity, he was nonetheless influenced by the wildness of a Chassidic wedding he attended and captivated by the paintings of Marc Chagall, both elements of which he incorporated into the play.

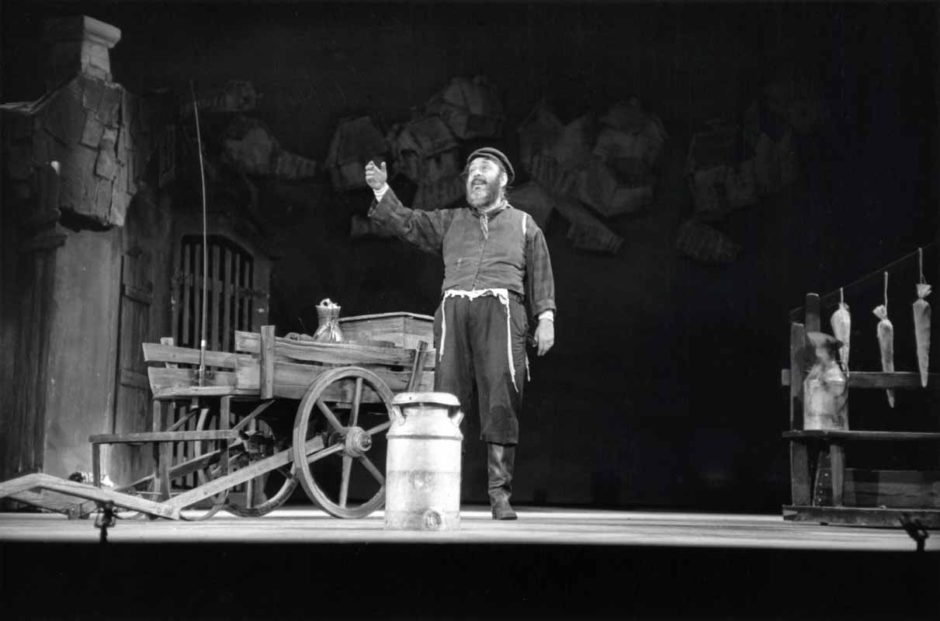

Lewkowicz also suggests that Zero Mostel, the first actor to portray Tevye, was just as hot tempered as him.

Norman Jewison, the non-Jewish director of the film version, tells a funny anecdote. “What would you say if I was a goy?” he asked the head of the movie studio, Arthur Krim. Having assumed that Jewison was Jewish, Krim was apparently surprised by Jewison’s disclosure. A deafening silence ensued before Krim disingenuously said, in effect, “That’s why we chose you.”

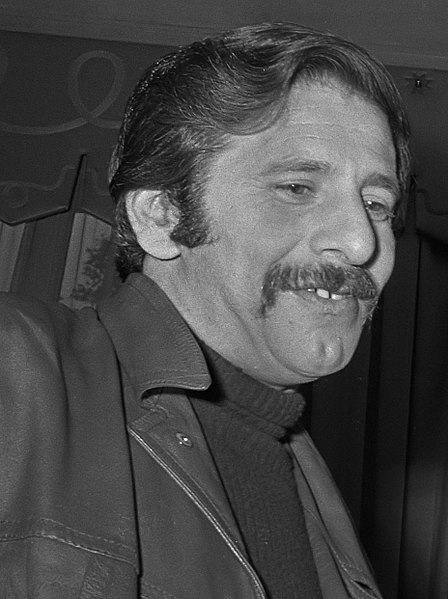

Jewison selected Chaim Topol, an Israeli actor working in London, as Tevye. Topol, he says, exuded power and sexuality. In one important scene, Topol adds, he had a terrible toothache. Which is perhaps why he made such a lasting impression.