Blood libel, the scurrilous ritual murder accusation that has been levelled against Jews, is one of those terribly false myths that has caused untold suffering over the centuries.

The accusation, which has been repeatedly denounced by Christian churches, is bound up with the patently absurd tall tale that Jews kill Christian children for ritual or medicinal purposes or to mock Christianity.

That Jewish law expressly prohibits the consumption of blood is absolutely of no concern to the accusers.

The blood libel calumny, which has resulted in the torture, death and expulsion of Jews, has been hurled against Jewish communities in Europe since the medieval era and in the Muslim world since the 19th century. It even cropped up in the United States in the 1920s.

Its origins have yet to be determined, but the earliest known blood libel case occurred in England in the mid-12th century, following the publication of The Life and Passion of Saint William of Norwich, a tract written by Benedictine monk Thomas of Monmouth.

Thomas concocted it after the mutilated corpse of a young apprentice leather worker, William, was found outside Norwich, the second largest city in England, in 1144. A local bishop, who had defended a knight accused of murdering a Jewish banker, claimed that William had been killed by Jews in mockery of Christ’s crucifixion.

Thomas, the monk, heard this story and began collecting notes about it. More than 20 years later, he finished The Life and Passion of Saint William of Norwich, in which he hailed William as a saint and claimed that his body had been mutilated by Jews.

Thomas’ outlandish tale spread beyond the boundaries of Norwich and became “firmly rooted in the European imagination,” writes E.M. Rose in The Murder of William of Norwich, published by Oxford University Press.

Eventually, as Rose points out, accusations of blood libel emerged in what is now Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Russia, Hungary and Greece, adding yet another toxic layer to the foundations of antisemitism.

In this illuminating book, which unfolds against the backdrop of the Second Crusade and the status of Jews in medieval society, Rose examines the incident that prompted Thomas to defame Jews and explains why it is so deeply rooted in cultural memory.

Norwich, a flourishing Norman city with close ties to the European continent and especially the Rhineland, was the governmental, ecclestiastical and economic center of eastern England in the 12th century. It was also one of the first cities outside London to which Jews moved.

By the start of the 13th century, about 200 Jews lived in Norwich, which had a population of 5,000. Jews were chiefly engaged in moneylending, which was forbidden to Christians, but were also involved in a variety of trades and commerce.

Until the appearance of The Life and Passion of Saint William of Norwich, Jews had not been subjected to violence in England. Thomas’ blood libel accusation, however, was a “turning point,” leading to the riots that surrounded Richard I’s accession to the throne in 1189 and the expulsion of Jews from England in 1290.

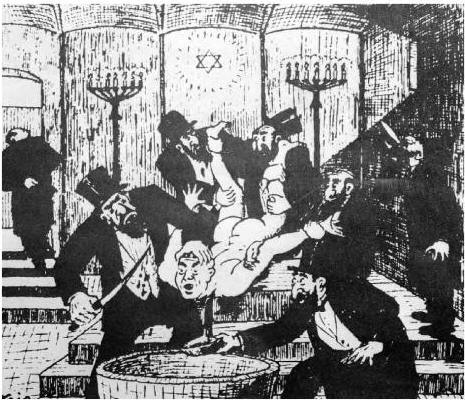

Even mere rumours of ritual murder provoked violent explosions throughout Europe in every century well into the 20th century. The Nazis particularly exploited the accusation.

Having seeped into the consciousness of Christians, the accusation worked its way into architecture, literature and art. As Rose puts it, “Variously enshrined in cathedrals, celebrated in ballads and songs, or depicted with the Virgin Mary in panel pieces and altar pieces, the purported victims were portrayed in manuscripts, sculpture, paintings and stained glass.”

Although the accusation has never withstood scrutiny, it has had, as Rose succinctly observes, “a pernicious and long-lasting history.”