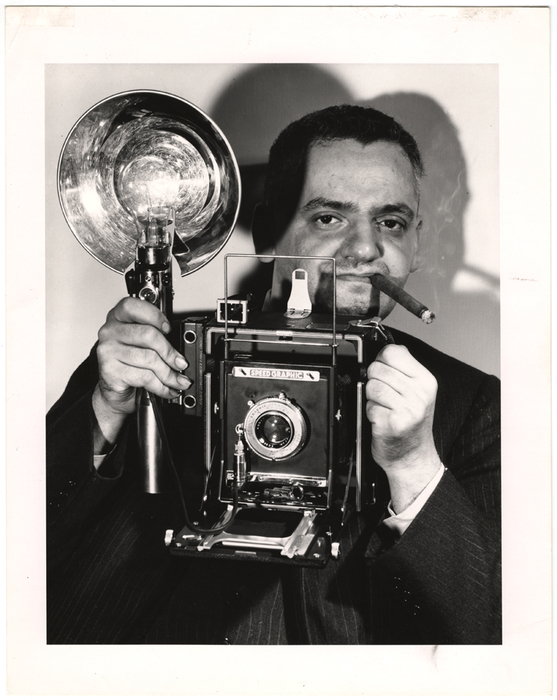

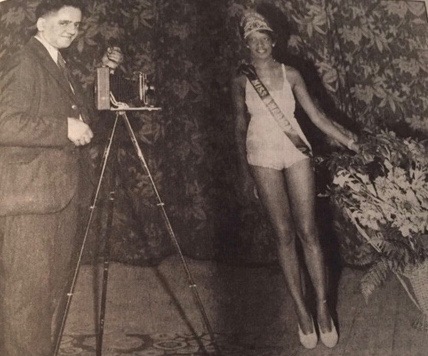

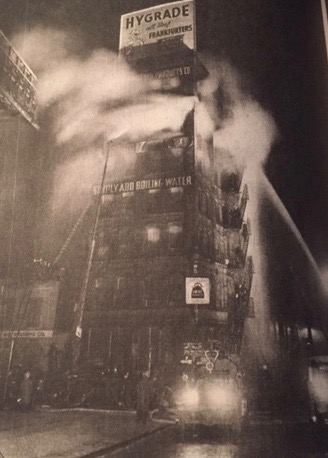

Roaming the streets of New York City at night with a Speed Graphic camera equipped with a flash, the self-taught, now-legendary photographer Arthur Fellig exposed the nooks and crannies of a great metropolis for millions of New Yorkers during the 1930s and 1940s. Freelancing for agencies like the Associated Press and the International News Service and for dailies ranging from The New York Daily News to The New York World-Telegram, Fellig, known in the trade as Weegee the Famous, caught the pulse of a city that never slept.

A squat fellow in a rumpled suit and a crumpled fedora, with a cigar clamped in the corner of his mouth, he specialized in crime, grit and humanity, using his talents to define a bygone era in the city’s history.

As was customary during that epoch, Fellig’s work was usually anonymous. But with the publication of his first book, Naked City, he shed his anonymity and gradually transformed himself into something of a celebrity. A retrospective, mounted in 1977, burnished his reputation as a profoundly skilled craftsman.

Fellig’s legacy is distilled by Christopher Bonanos in a remarkably vivid book, Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous (Henry Holt and Company).

Bonanos, an editor at New York magazine, compares Fellig to a Damon Runyon character. But when he arrived at Ellis Island in 1909 at the age of 10, he was little more than “a greenhorn, a hungry shtetl child from Eastern Europe who spoke no English.”

He was born in Zolochev, a town near Lviv, which was then in in the Austro-Hungarian empire but which is now part of Ukraine. Like many Jewish newcomers, he changed his first name, calling himself Arthur. Although smart and ambitious, he dropped out of school in grade seven, thinking he could make his way in the world without a proper education.

Finding his niche in photography, he was a darkroom technician for both The New York Times and the Acme Newspictures agency. In 1934, he left Acme, never to hold a regular job again. “I took my little camera and I started hanging around police headquarters, at the teletype desk, and took pictures,” he recalled.

He sold his photographs to the dailies, which always had news holes to fill. Occasionally, the Jewish Daily Forward, published in Yiddish, and the Daily Worker, the organ of the American Communist Party, bought his pictures. Life, the mass-circulation magazine, purchased his work as well.

“One good murder a night, with a fire and a holdup thrown in” was his nightly goal. What set him apart from his now-forgotten competitors, says Bonanos, was his quest for imparting emotion. “When I watched the other photographers on stories,” Fellig would write, “I saw that they used the camera like a machine and that they thought like machines. My idea was to make the camera human. I was dealing with people at their most tragic moments — fires, murders, etc. — and all this I tried to show in my pictures.”

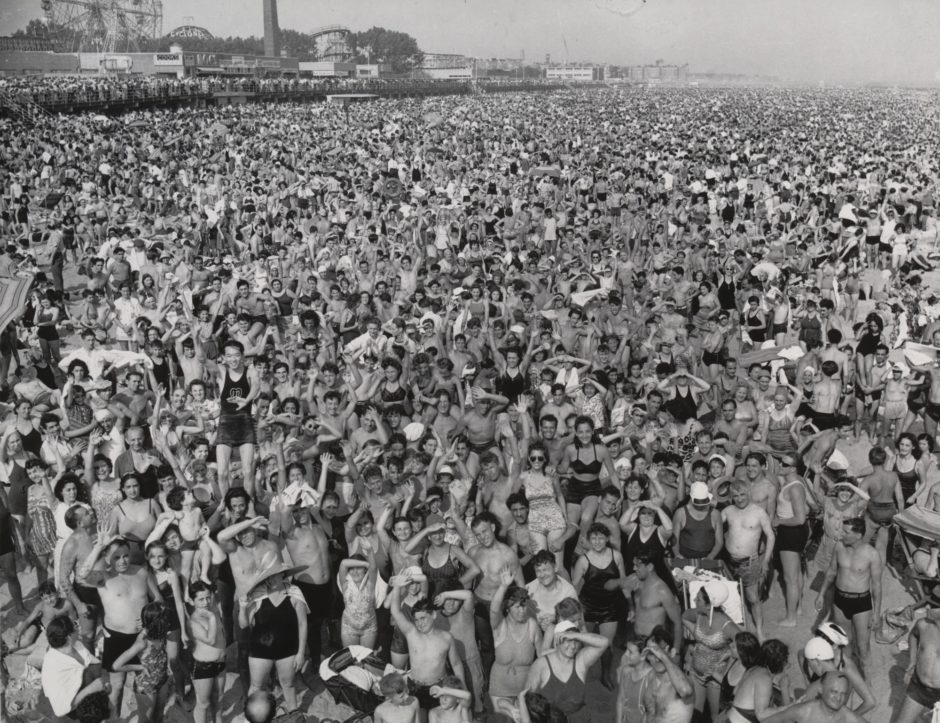

Fellig, too, caught New Yorkers at play. His photograph of Coney Island beach in 1940 brims with bathers and sun seekers and speaks to the universal allure of the ocean.

In Bonanos’ judgment, Fellig’s photography usually rose to a high level. “His best pictures are intensely truthful. Some are painful, others unexpectedly warm, many others funny, touching, memorable.”

Fellig’s career blossomed after PM, a left-of-center daily, put him on a retainer of $75 a week.”That was upper-middle-class money for a single man in 1940, nearly as much as he’d been making as a freelance,” says Bonanos.

Naked City, published in 1944, was his first of five books. It sold well but didn’t quite crack The New York Times‘ best seller list. Nonetheless, a bevy of national magazines offered him assignments. All the while, he continued with his bread-and-butter newspaper work. His next book, Weegee’s People, depicted impoverished New Yorkers struggling to survive.

In 1947, he moved to Los Angeles, where he was a jack-of-all trades. Trying his hand at acting, he appeared in cameo roles in several movies, including Otto Preminger’s light comedy, Every Girl Should Be Married, starring Cary Grant. And he perfected the Elastic Lens, a device that enabled him to distort photographs artistically.

But after three years in Hollywood, he had enough. “He’d worked on a handful of movies and accumulated perhaps ninety seconds of screen time all told, with barely enough lines of dialogue to fill a single page,” says Bonanos. “He’d been well paid for his trick lens, but that work was inconsistent, providing neither the level of attention nor the artistic engagement to which he’d grown accustomed.”

Returning to Manhattan, he signed up with a speakers’ bureau and wrote Naked Hollywood, a sensationalist volume which critics lambasted.

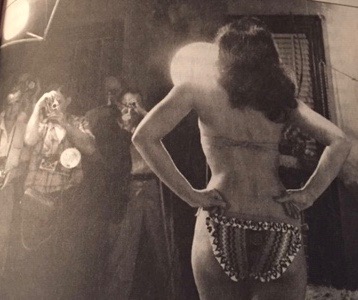

Turning his attention to Bettie Page, a buxom pinup girl, Fellig photographed her multiple times. “At least once, on a shoot where she was posing in a bathtub, he tried to climb in with her, ostensibly to improve his camera angle. ‘Out, Weegee, out,’ she shouted at him,” Bonanos reports.

In the mid-1950s, he devised a new technique of manipulating images, producing prints through textured glass and rippled sheets of plastic rather than through the Elastic Lens. “Effectively, he was turning himself into a caricaturist, exaggerating features to emphasize or tweak the personae of public figures,” says Bonanos.

On one of his last projects, he took still photographs for movie director Stanley Kubrick on the set of Dr. Strangelove: Or How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. “The pictures turned out to be superb,” Bonanos notes. “They’re the last truly great body of work Weegee made in his life, a real return to strength. They had that intense caught-in-action strangeness, the otherworldly real quality that suffused, say, his best nighttime fire photos.”

Fellig died in 1968 of a malignant brain tumour. By then, six of the nine New York dailies to which he had contributed had folded.

Since his death, he has been the subject of a retrospective by the International Center of Photography in New York and of a book. In addition, Fellig’s own books have been reissued in paperback editions.

In 1998, his ashes were scattered at sea. “No pictures were taken,” says Bonanos laconically.