Ami Ayalon describes himself as “a strange bird” and an “outsider” in his frank and heartfelt memoir, Friendly Fire: How Israel Became Its Own Worst Enemy And The Hope For Its Future (Steerforth Press). Ayalon’s self-portrait is true, yet false. Having held top-level governmental posts in Israel, he is very much of an insider. But in light of his unorthodox views concerning Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, he deviates from the mainstream.

Neither a leftist nor a rightist, but rather a “pragmatic humanist,” Ayalon is an Israeli patriot and a fervent Zionist who thinks that Israel can best secure its future as a Jewish democratic state by coming to terms with the Palestinians within the framework of an equitable two-state solution.

Until about 25 years ago, his views were conventionally right-wing. He regarded the Palestinians as irreconcilable enemies and assumed that the territories the Israeli army had conquered in the 1967 Six Day War were Israel’s to keep in perpetuity.

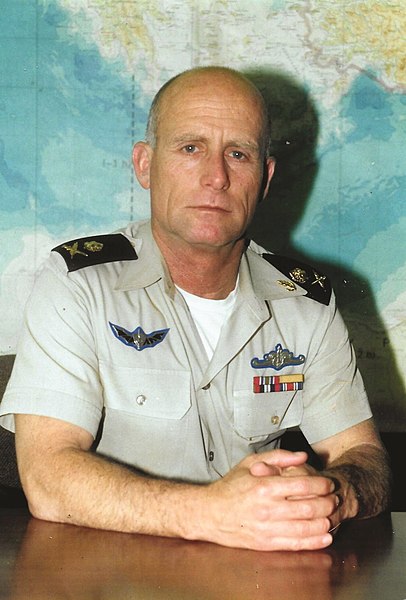

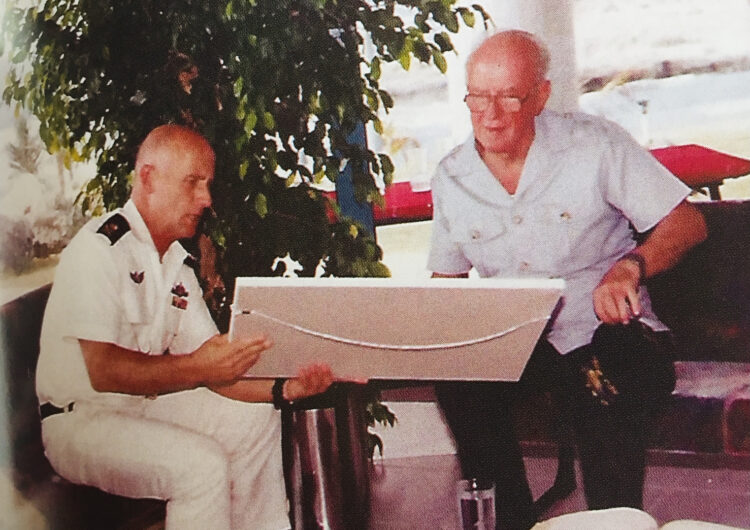

Born on a kibbutz, the son of Romanian Jews who immigrated to Palestine in 1938, Ayalon was an officer in Israel’s special forces for 22 years. He was successively the commander of the Israeli Navy from 1992 to 1996, the director of the Shin Bet internal intelligence agency from 1996 to 2000, and a member of the Knesset and a cabinet minister from 2006 to 2008.

In 2002, as the second Palestinian uprising raged, he and Sari Nusseibeh, the president of Bir Zeit University, launched the People’s Voice campaign to promote a peaceful resolution of Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians.

Dennis Ross, an American diplomat who was deeply involved in Middle East diplomacy during the presidencies of George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, met Ayalon when he directed the Shin Bet. Calling him a “remarkable man” in the book’s foreword, Ross says that Ayalon came to realize his approach to the Palestinians was essentially outdated and counter-productive, and that Israel’s policies were leading it toward a one-state solution in which it would lose its character and identity.

“He wants his fellow Israelis to accept that while the Jewish people have a right to self-determination in a land of their history, it it not an exclusive, absolute right,” writes Ross. “That is why he believes in two states for two people.”

In the prologue, Ayalon gets to the point quickly: “My experiences in and out of the (Shin Bet) interrogation room … shattered my lifelong preconceptions about Palestinians. If we wanted to end terrorism, we couldn’t continue regarding them as eternal enemies, and we needed to stop dehumanizing them as animals on the prowl. They are people who desire, and deserve, the same national rights as we have.”

During his time in the Shin Bet, Ayalon developed sensors that took him beyond his customary “us-versus-them” thinking. He learned that when Israel carries out anti-terrorist operations in “a political context of hopelessness, the Palestinian public supports violence, because they have nothing to lose.”

Ayalon’s refreshingly honest observations extend to his personal life. As he admits early on in this illuminating volume, part of the the building he and his wife, Biba, live in once belonged to an Arab family in the village of Ijzim, located on the southern slopes of Mount Carmel. The owners fled in 1948, during the first Arab-Israeli war, and Ijzim was renamed Kerem Maharal and converted into a cooperative community, or moshav. The newer section of their house was built in the 1950s to shelter Holocaust survivors from Czechoslovakia.

Ayalon’s father, whose original name was Hirsch, arrived in Palestine from Transylvania aboard a small freighter. He was a founder of Ma’agan, a kibbutz on the southern shore of the Sea of Galilee where, incidentally, I was briefly a volunteer after the Six Day War. Once a British army base, Ma’agan is close to the pre-1967 Syrian border. The kibbutz plantations where bananas and mangoes are grown today housed the Arab village of al-Samra prior to the War of Independence.

Raised in this sylvan milieu, Ayalon considers Ma’agan his “spiritual home,” the place where he could “ramble, swim and dream of a better world.”

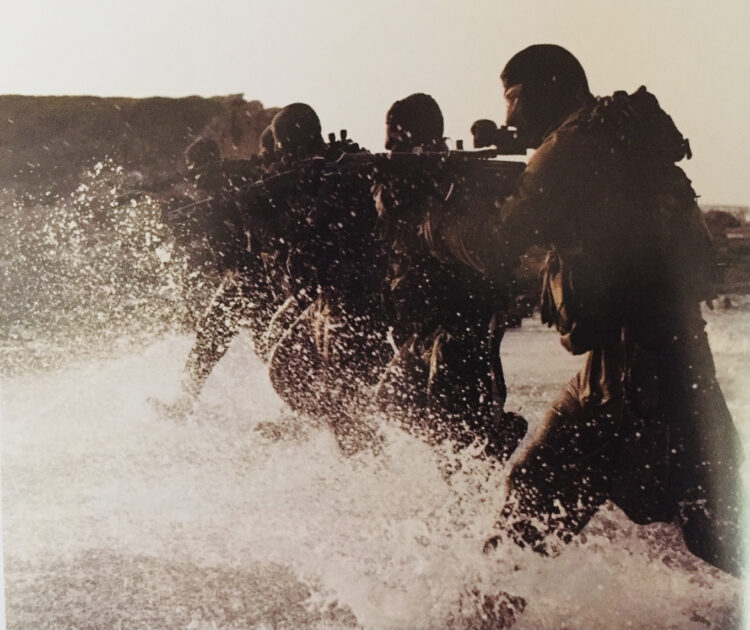

During his boyhood, he admired military power, dreamed of joining the elite Flotilla 13 naval commando force, and identified with the Jewish pioneers who “entered the Land of Israel and kicked ass.”

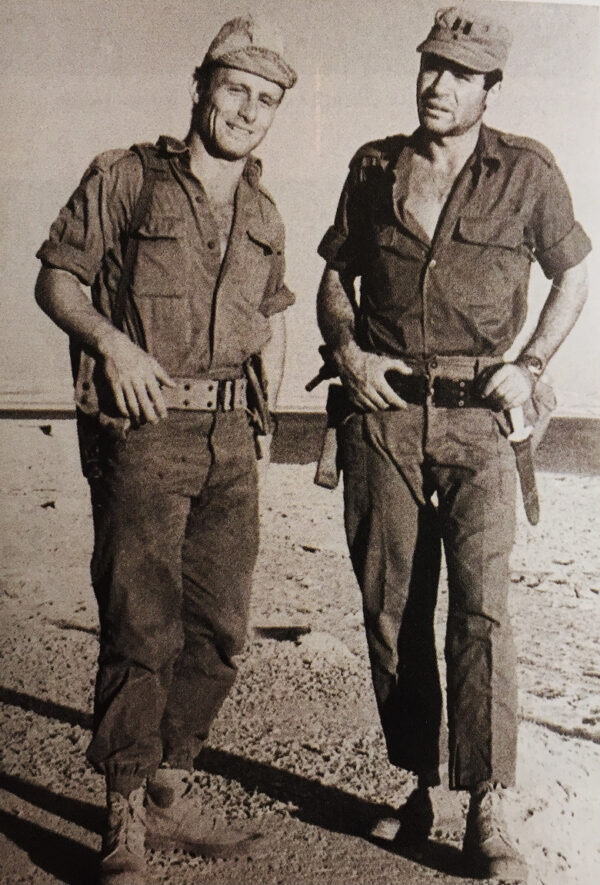

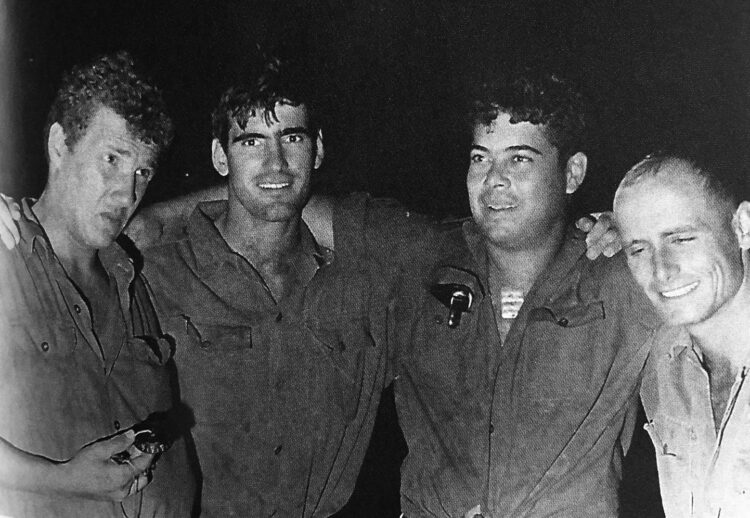

He signed up for Flotilla 13 in 1963, when he was 18, motivated by the thrill of adventure and danger. During the War of Attrition following the Six Day War, Ayalon participated in a number of operations, most notably in the 1969 raid on Egypt’s Green Island, “the first such attack on this scale in the history of marine warfare.” Seriously wounded during the fighting, he earned a Medal of Valor, Israel’s highest military decoration, in recognition of his heroism.

These were the years when Ayalon supported Israel’s settlement project in the occupied areas with “every fibre of my being.” Today, he is convinced that Israel built settlements in direct violation of international law, which forbids an occupying power from building on conquered lands.

During the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Ayalon commanded an armada of ships that sunk dozens of Egyptian vessels. After the war, he was placed in charge of a base in the northern Sinai Peninsula. After rejoining Flotilla 13, his missions were to disrupt the smuggling routes of the PLO and sabotage weapon depots inside its camps. From 1982 to 1985, he was responsible for guarding Israel’s coastline from Hadera to the Egyptian border. Later, he headed Israel’s navy, the culmination of a 30-year naval career.

By then, his views of the Palestinians had yet to evolve. “In a prime example of colonial wishful thinking, I assumed poverty, not patriotism, was driving (them) to violence. If we could just prop up their economy, they’d submit to our rule and would eventually seek peace on our conditions.”

It was during the first Palestinian uprising, which lasted from 1987 to 1991, that Ayalon recognized “the futility” of trying to “control” the Palestinians of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

He agrees that many Israelis lost confidence in the Oslo peace process due to the upsurge of Palestinian terrorism. “Yet for Palestinians wishing for an end to our occupation and the establishment of their own state alongside Israel, the past twenty years have brought only more settlements and more Israeli army incursions, a deepening occupation. In their eyes, we are the betrayers, the unreliable negotiating partner.”

To Ayalon, the Oslo-directed partition of the West Bank into three separate zones has given the Palestinians little more than “an archipelago of apartheid-style Bantustans split up and surrounded by territory controlled by Israel.”

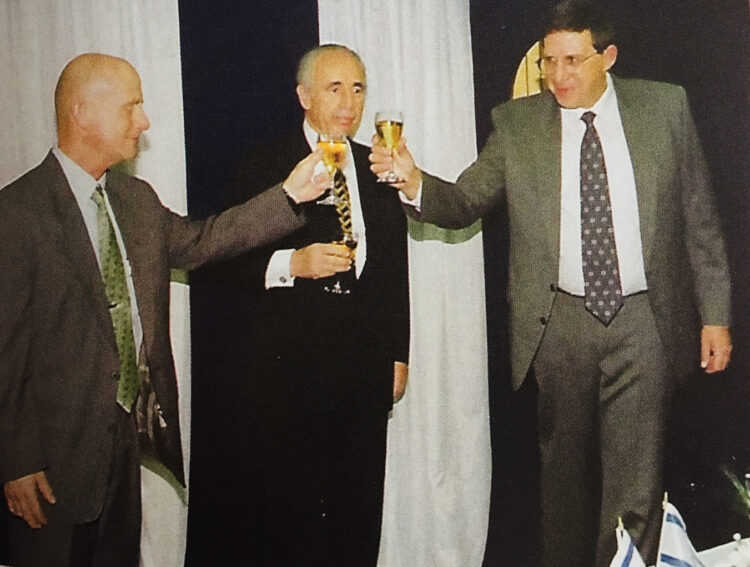

With the Shin Bet having failed to squelch the worst bout of terrorism in Israel’s history, the then prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, offered Ayalon the job as its director. “Rabin needed someone new at the helm, an outsider who could shake up the agency,” he says. He rejected the offer, feeling he was not the right person for that post. But after Rabin’s assassination in 1994, Shimon Peres, his successor, extended the same offer to Ayalon. “With the (Shin Bet) reeling from its failure to protect both the prime minister and Israeli civilians from terrorism, this time around I felt it was my duty to accept.”

Ayalon’s mandate was daunting — to stop the bombings, to prevent the West Bank and the Gaza Strip from erupting into flames, and to provide objective information to the prime minister. In other words, he was to be a “gatekeeper.”

He got off to a poor start. In his first two weeks as director, 59 Israelis were killed in suicide bombing attacks, most of which were perpetrated by Hamas. Ayalon concluded he would require the assistance of Palestine Authority President Yasser Arafat to hunt down terrorists. “In the end, only Arafat could defeat Hamas, because almost all Palestinians still lined up behind his vision of national independence. So if the Palestinian Authority worked with us to fight Hamas, we … would have to follow through on the terms of Oslo and withdraw from over 90 percent of the occupied territories.”

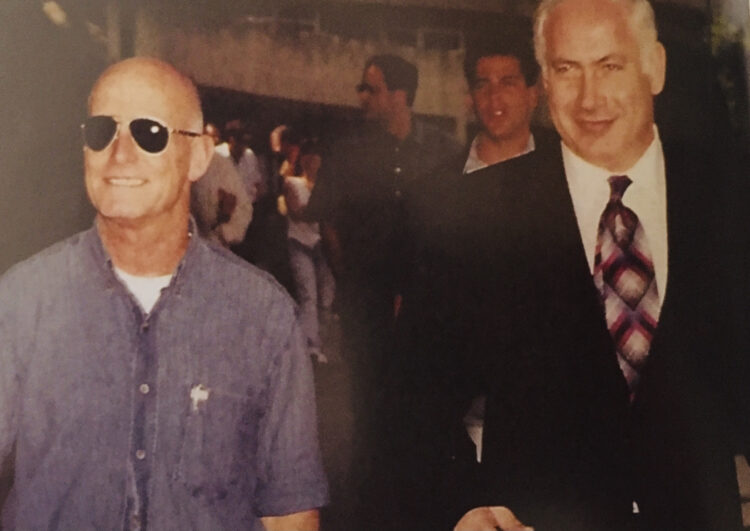

The new Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, seemed to flinch when Ayalon mentioned this. “I left his office that day in the dark as to what he thought about my counsel. But when I saw his cabinet ministers doing their very best to undermine Oslo, I understood that the settler faction inside his government and his political base among the Greater Israel right-wing held a lot more sway over him than we in the (Shin Bet) did.”

As he settled into his job, Ayalon decided that Shin Bet interrogation methods with respect to captured terrorists were in dire need of an overhaul and “a moral compass.” As he puts it, “What we needed was to draw a bold red line between permitted and prohibited techniques.”

Having spent time overseeing operations and maintaining contacts in the West Bank and Gaza, Ayalon began to realize that Israeli policies were part of the problem. “I had begun to see that more bypass roads, military outposts and settlements would eventually destroy any hope of a two-state solution. If we kept up the building, before too long the Palestinians would conclude we had no intention of ending the occupation and allowing a Palestinian state alongside Israel. This would inevitably lead to the loss of hope and the triumph of terror.”

Much to Ayalon’s disappointment, Netanyahu’s successor, Ehud Barak, an old colleague, focused his attention on reaching a peace agreement with Syria rather than with the Palestinians. Ayalon warned him that if the peace process on the Palestinian front faltered, a violent popular uprising would break out. He was absolutely correct.

Barak, on the other hand, had lost touch with reality, he claims. “He didn’t feel the rising temperatures, the waves forming whitecaps, the black cirrus clouds — the telltale signs of a hurricane coming our way.”

To Ayalon, the impasse between Israel and the Palestinians was as clear as day: “Most Israelis continued to believe we wanted security and got terror, while Palestinians, who wanted independence, felt they had only gotten more settlements, more military occupation, and more humiliation at checkpoints.”

Unlike Rabin, Barak failed to build a partnership with Arafat, mistakenly claiming that Israel did not have a partner on the Palestinian side. The ‘no partner’ line proved catastrophic to Israeli interests, he says.

He adds, “We never struck a balance between identifying security dangers and identifying the opportunities for peace.”

Fed up with Barak, Ayalon resigned, taking a position as chairman of a drip irrigation company founded by a kibbutz in the Negev Desert. “It was a way to get back to my kibbutz roots while making a contribution well beyond Israel’s borders,” he says. “I also got to be a full-time husband and father for the first time.”

Ayalon devotes a chapter to the People’s Voice campaign, which elicited the support of almost half-a-million Israelis and Palestinians. Their plan for a two-state solution, based on the June 4, 1967 borders and on land swaps, envisioned a demilitarized Palestinian state, with Jerusalem as the open capital of both states.

He entered politics in 2006 with the goal of becoming prime minister. “Stating my ambition so bluntly was the first of many mistakes I would make in politics,” he concedes.

Amir Peretz, the leader of the center/left Labor Party, offered him a top spot on its list. Labor would become a junior member of the governing coalition led by Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s centrist Kadima Party. Ayalon would be a member of the Knesset’s influential Foreign Affairs and Security Committee.

Ayalon disagreed with Olmert’s hasty declaration of war against Hezbollah after its operatives killed several Israeli soldiers in an ambush inside Israel’s territory. But he was impressed by Olmert’s desire to forge peace with the Palestinians. Offering him a seat in the cabinet, Olmert said, “I want you in my government because I believe your vision for a future agreement with the Palestinians is our best chance for peace.”

Tragically, Olmert’s initiative crashed and burned a month later after the attorney-general accused him of fraud and breach of trust and he was forced to resign. Nevertheless, Ayalon gives him a lot of credit: “No prime minister had ever pursued a deal with as much conviction.”

After Barak succeeded Peretz as the Labor Party’s leader, Ayalon resigned from the cabinet. Although he has forsaken politics, Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians still weighs heavily on him.

Toward the close of Friendly Fire, he reiterates that Israel needs to withdraw from most of the West Bank if it is to maintain its identity as a liberal democracy. As he told Nusseibeh, “We’ll never make peace until we change the narrative about the past and admit to ourselves that the Palestinians have a right to their own country alongside Israel, and on land we claim as ours.”

Elaborating on this theme, he imagines what the message of a future Israeli prime minister would be to his people. “Our war to preserve our security and independence is inseparable from our decision to end our apartheid regime in the occupied territories … and allow the Palestinians to exercise national self-determination …”

It’s an idealistic, yet sober and realistic, vision of what is needed to advance the prospects of peace.