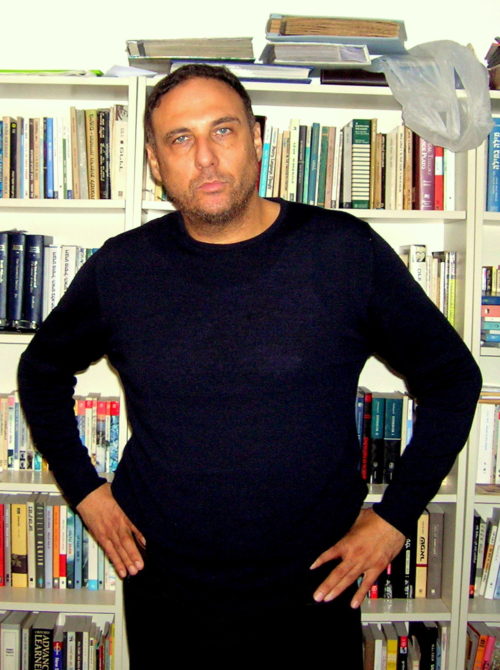

Yossi Sucary calls it the “unspoken Holocaust.”

Sucary, an Israeli academic and author, is referring to the little-known fact that the Jews of Libya were among the six million victims of the Holocaust.

Jews in Israel and the Diaspora generally assume that only European Jews were caught up in the Holocaust, but this assumption is a myth, he said in a lecture on March 30 at the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Toronto.

Recalling his childhood in Ramat Gan, a suburb of Tel Aviv, Sucary said his teacher would berate him for believing that his Benghazi-born grandmother had been deported to Bergen-Belsen, a German concentration camp liberated by the British army in April 1945.

“She told me, ‘You’re wrong. Only European Jews were in the Holocaust.'”

Libyan Jews suffered terribly following the relatively brief German occupation Libya in 1942, yet the vast majority of Israelis still think that only European Jews were affected by the Holocaust. “We called it the unspoken Holocaust,” said Sucary, who teaches at the Tel Aviv College of Management.

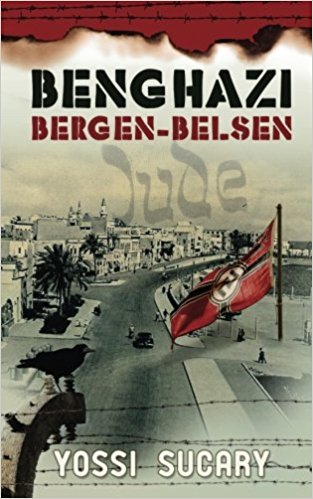

As a result of this widespread misconception, he wrote a novel about the trauma that Libyan Jews endured during World War II. Benghazi-Bergen-Belsen, originally published in Hebrew in 2014 and the winner of the Brenner Prize for Hebrew Literature, has been added to the Israeli education curriculum.

Now out in an English translation, it’s the first novel, in any language, to deal with this singular topic. Sucary’s novel is based, in part, on the horrible stories he heard from his grandmother.

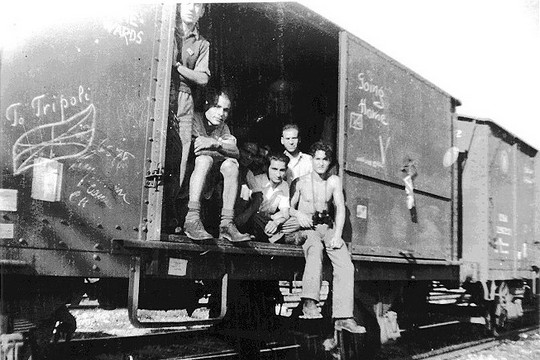

After seizing control of the country, the Germans sent about 1,000 Libyan Jews to three concentration camps — Gharyan, Jado and Said al-Aziz — where they were subjected to Nazi brutality, starvation and death. Some of the Jewish prisoners, including Sucary’s grandmother, were transferred to to Bergen-Belsen, and Birenbach Reiss, via Italy.

His grandmother, having previously lived in Egypt, held a British passport, like many well-to-do Libyan Jews. The Germans hoped to trade their Jewish captives for German prisoners-of-war, said Sucary.

For the Libyan Jewish captives, the European landscape presented challenges. “They came from the Sahara desert, never having seen snow before,” he said.

In Bergen-Belsen, Jewish inmates treated Libyan Jews like Sucary’s grandmother with disdain bordering on racism, as if they had come from an inferior culture.

From 1911 onwards, Libya — a former Ottoman domain — was an Italian colony. Jews and Arabs lived in harmony there, according to Sucary. From the late 1930s onward, the Libyan Jewish community was subjected to antisemitic laws and restrictions by the fascist Italian government of Benito Mussolini.

In neighbouring Tunisia, which Germany also occupied briefly, Jews were deprived of their civic rights and dispatched to labor camps. Some Tunisian Jews living in France were deported to Nazi extermination camps in Poland.

After the war ended, pogroms broke out in Libya, prompting the mass departure of Libyan Jews to two major destinations: Israel and Italy. Still more Jews left in the wake of the 1967 Six Day War. No Jew are believed to be living in Libya today.