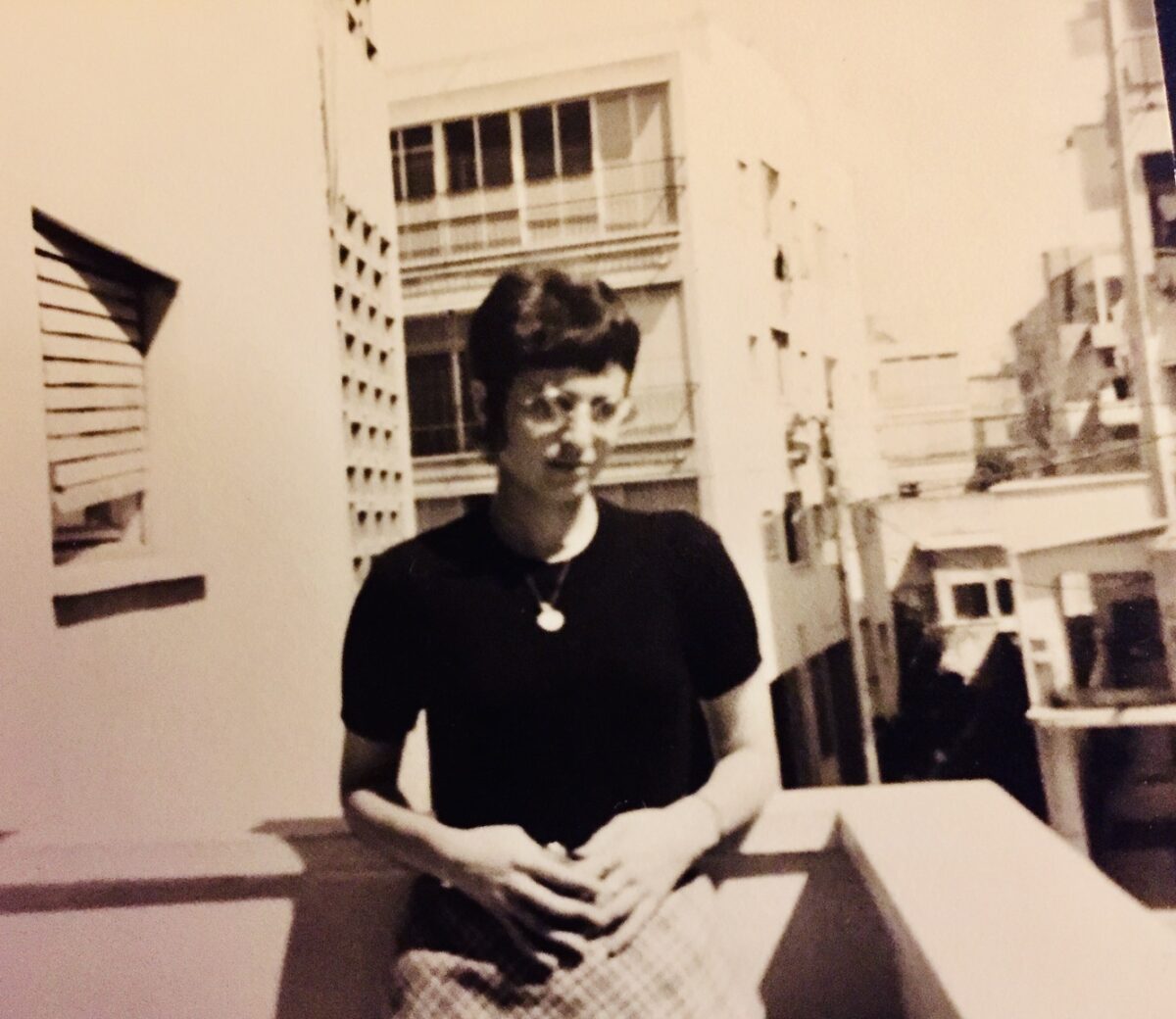

My first sustained exposure to Jaffa, a quaint and somewhat rundown neighborhood of Tel Aviv, occurred toward the end of 1971, shortly after I met my wife-to-be, Etti, a student at Tel Aviv University finishing an MA degree in English literature.

We met at the British Council Reading Room in one of the university’s libraries. I was writing an aerogram to my parents, informing them of my decision to return to Montreal. I had spent less than a year in Israel, studying Hebrew at an ulpan and working on a kibbutz, and now it was time to go back to Canada.

Etti upended my plan.

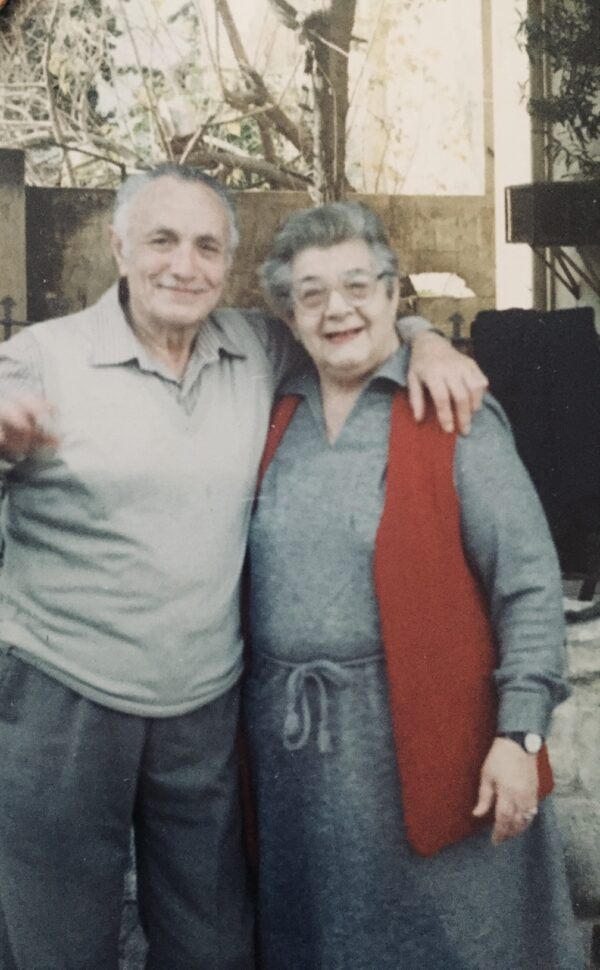

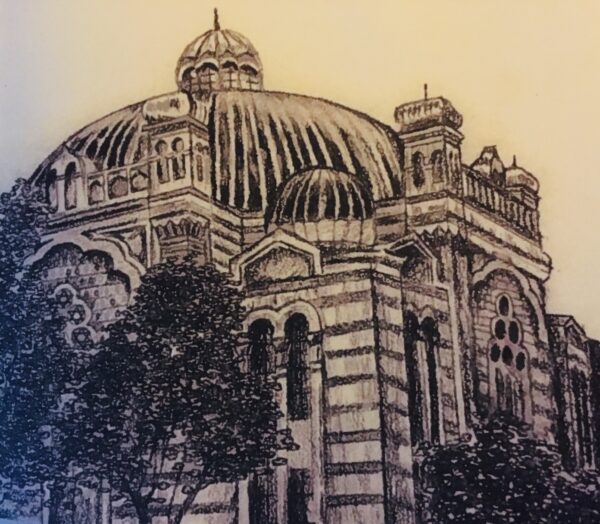

Not long after our meeting, she called to invite me to her parents’ home in Jaffa. Etti and her mother and father, Reni and Moritz Lazarov, were the first Bulgarian Jews I had ever met. From that point forward, I was introduced to their culture, language, history and culinary preferences (ah, Creme Bavaria), and to Jaffa, a bastion of the Bulgarian community in Israel.

As we got to know each other, Etti showed me around Jaffa. I appreciated its ragged Oriental flavor, liked its groceries, boureka cafes, bakeries, and was struck by its flea market, Ottoman clock tower, crumbling facades and wall facing the foaming Mediterranean Sea. I had briefly visited Jaffa in the wake of the 1967 Six Day War, but never before had I been so exposed to its nooks and crannies and nuances.

Six years later, my appetite whetted for all things Bulgarian, my friend Henry Srebrnik and I travelled to Bulgaria, a country Etti has yet to visit, though she was born in Sofia, its capital city. It was there that I expanded my knowledge of Bulgaria’s Jewish community, one of only two in Nazi-occupied Europe to survive the Holocaust more or less intact.

When I learned that Wayne State University Press in Detroit had published Sofia to Jaffa: The Jews of Bulgaria and Israel, I ordered it immediately. Though I had read books and articles about Bulgaria and its Jews, I was eager to wade into Guy H. Haskell’s book.

Haskell, the general editor of the Jewish and Ethnology Review, has written what may be the definitive work on this somewhat esoteric subject. In fluid and authoritative fashion, he traces the history of Bulgaria’s largely Sephardic Jewish community from mainly the Ottoman period to the present. He then segues into the tragic events of World War II, which placed Jews in dire peril and eventually prompted most of them to immigrate to Israel in a historic movement of mass migration.

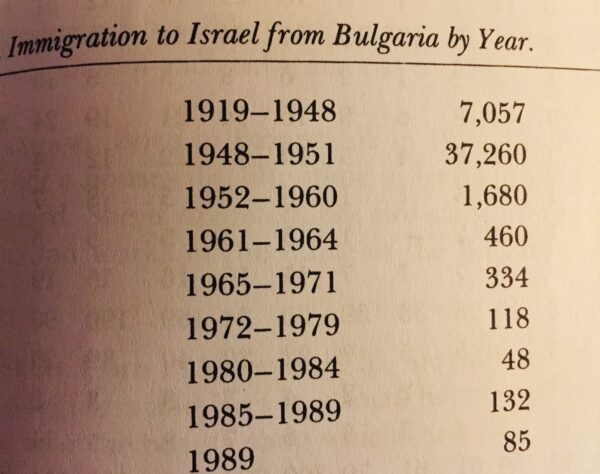

From the moment of Israel’s birth in 1948 until 1951, 684,000 new Jewish immigrants poured into the country, thereby tripling its population.

Forty five thousand of the newcomers, including Moritz and Reni, were Bulgarians. They settled in Jaffa, which had been populated mainly by Palestinian Arabs prior to the first Arab-Israeli war. Their first home was in Jaffa’s Gan Tamar district. Later, they purchased a small and unassuming flat nearby.

Moritz and Reni left a country that had persecuted its Jewish citizens in the early 1940s. Until Bulgaria’s alliance with Nazi Germany, Bulgarian Jews were comfortably off. Bulgaria, during the Turkish Ottoman era from 1389 to 1878, treated its Jewish minority fairly well. “The consolidation of Turkish sovereignty over Bulgaria provided its Jewish population with a measure of security and protection unmatched anywhere in Christian Europe,” writes Haskell.

Whereas the Ottomans regarded Christians with some disdain, they generally respected and valued Jews. “Unlike the Christians, who were largely illiterate peasants, the Jews could not only govern themselves efficiently, but their acumen in trade and diplomacy and their linguistic competence was of great benefit in linking the (Ottoman) empire in a comprehensive, cosmopolitan network.”

Under the Ottoman millet system, Jews were a protected minority who exercised control over their community. In exchange, they were expected to defer to Ottoman authority and pay special taxes.

Nearly all Bulgarian Jews lived in the cities and earned a living as artisans and merchants. Turkish, Greek and Ladino were the languages of trade, French was the language of culture, and Hebrew was the language of prayer and scholarship. Until the 20th century, Jews possessed only a cursory knowledge of Bulgarian.

When Bulgaria was liberated by the Russian army in 1878, the Jewish community, though bereft of great scientists or rabbis, was united and well organized. Within 40 years of Bulgaria’s liberation, the Jewish community, having liberalized and secularized itself, embraced Zionism.

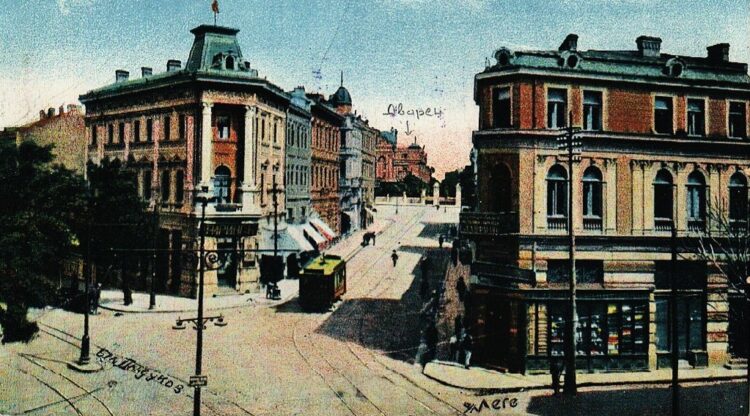

Long before the founder of political Zionism, Theodor Herzl, visited Sofia in 1896 en route to Constantinople, Zionist societies had sprung up in the capital, Plovdiv and Khaskovo. Unlike some Jews in Europe, most Bulgarian Jews saw no contradiction between Judaism and Zionism.

As a result, they were oriented toward Zionism and Palestine. As Haskell puts it, “The language, symbols, holidays, dances, songs, images, longings and goals of the Zionist movement suffused the community, supplanting many of the Sephardic traditions withering from exposure to modernity, and filling some of the spiritual emptiness left by the fading of traditional religious observance and belief.”

There were 20,000 Jews in Bulgaria when it won its belated independence. By 1934, Bulgaria was a home to 48,500 Jews, with roughly half residing in Sofia. Jews and Muslims respectively comprised .08 percent and 13.5 percent of Bulgaria’s population. “By the 1930s, the Jews comprised the most urbanized and cosmopolitan sector of Bulgarian society,” says Haskell.

Although Jews were moderately influential in the economy, they seldom reached positions of importance in politics, the civil service and the armed forces. Being relatively few in number, they were “left in peace,” Haskell says, referring to the low level of antisemitism.

The fairly tolerant atmosphere dissolved in the 1930s as Germany increased its influence in Bulgaria and as Bulgarian students returned from their studies at German universities.

With the Bulgarian government pressing its irredentist claims against Yugoslavia, Greece, Romania and Turkey, Bulgaria formed an alliance with Germany. “The pro-German government was willing to accept Germany’s terms of alliance, including its demands that it take measures to ‘solve the Jewish problem,'” says Haskell.

In what was regarded as a decisive turning point, Bulgaria passed the Law for the Defence of the Nation, the first anti-Jewish edict, in December 1940. It was based on Germany’s antisemitic Nuremberg laws of 1936. Severe restrictions were imposed on the community, Jewish males were forced into labor battalions, and the bureaucratic apparatus for the “resettlement” of Jews in Eastern Europe was established.

The law did not enjoy popular support among Christians, but it was ratified by the government. New antisemitic laws were promulgated in 1942. One of them required Jews to wear the dreaded yellow star in public.

Bowing to German pressure, Bulgaria agreed to deport 20,000 Jews to Nazi-occupied Poland. The agreement was jointly signed in 1943 by Alexander Belev, the Commissioner for Jewish Affairs, and by Theodor Dennecker, a senior SS official.

Twelve thousand Jews from Bulgarian-occupied Thrace and Macedonia were deported and killed in Nazi extermination camps.

Bulgaria was prepared to deport a further 8,000 Jews, all Bulgarian citizens. They were to board trains from the town of Kyustendil, but the order was delayed due to resistance from the municipality. It was officially cancelled by the minister of interior after protests were sent to the cabinet, parliament and King Boris III by unions representing writers, lawyers and physicians. The head of the Orthodox Church, Stephen of Sofia, a friend of the chief rabbi, Dan Ziyon, objected as well.

Flabbergasted by this turn of events, the German ambassador in Sofia, Adolf-Heinz Beckerle, wrote a letter to a colleague in Berlin which, in part, read: “I beg you to believe me that my service is doing everything possible to reach a final solution to the Jewish question in conformity with decisions taken. I am deeply convinced that the prime minister and the Bulgarian government also desire a final settlement of the Jewish problem and are trying to reach it. But they are forced to take into account the mentality of the Bulgarian people, who lack the ideological and conceptions that we have. Having grown up among Turks, Jews, Armenians, the Bulgarian people have not observed in the Jews faults which would warrant special measures against them.”

The wave of protests, however, did not deter the Bulgarian regime from ratcheting up the persecution of Jews. In June of 1943, all Jews were ordered to leave Sofia for towns in the provinces.

The role of King Boris III in the disenfranchisement of Jews remains unclear, Haskell contends. Supporters claim he delayed the anti-Jewish edicts for as long as he could. Detractors argue he knew exactly what was happening. The bottom line is that he had “no great love” for Jews and regarded them as bargaining chips.

As Haskell writes, “With each battle lost, the (Bulgarian) government became more aware of the possible consequences of its anti-Jewish measures. In November 1943, a new cabinet was formed, headed by Dobri Bozhilov, which began to make concessions on matters affecting Jews. At the same time, it was secretly sounding out the Allies on possible agreements.”

Allied bombings of Bulgarian cities in January 1944 created panic and discontent, prompting Bulgaria to drop its plan to deport Jews. And with the Soviet army poised on its borders, Bulgaria abolished its antisemitic laws altogether.

Yet, as Haskell observes, the damage Bulgaria inflicted on its Jewish citizens was immense: “Although not deported to the death camps, the Jews were severely persecuted, and their lives were completely disrupted. They were threatened with imminent extermination and forced into banishment, forced labor and poverty.”

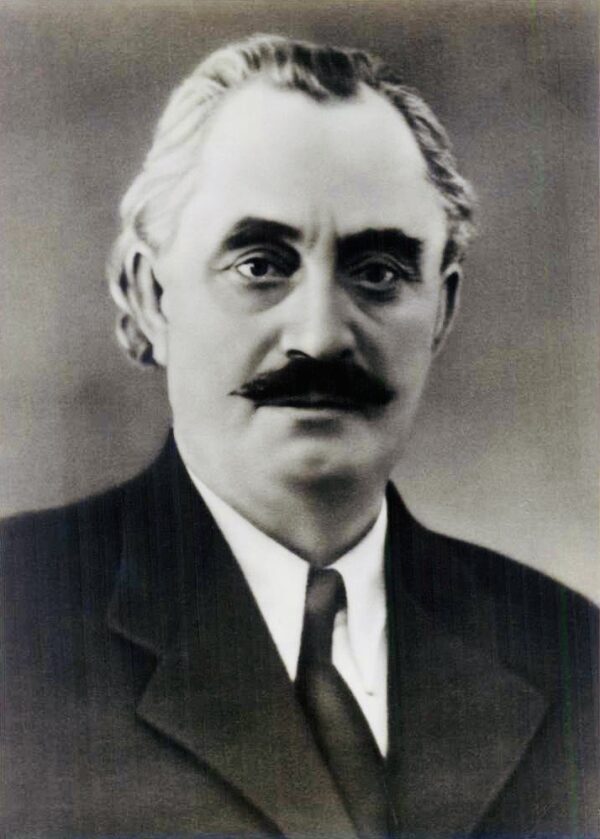

With the Communist Party in charge during the postwar period, Jews experienced still more stress and strain. The prime minister, Georgi Dimitrov, denounced the Holocaust, referring to Jews as “our Jewish brothers.” But he urged Jews to assimilate. “The greatest duty of the Jewish people is not to be different, but to participate in the most active and loyal way with all their might and ability in the construction of our homeland.”

Jewish communists, a tiny minority among Bulgarian Jews, endorsed his vision, but most Jews disagreed with it. As Haskell puts it, “Having maintained a vigorous and independent life on Bulgarian soil for over a millennium-and-a-half, and having just emerged from the clutches of oppression and threatened extinction, Jews had a different agenda.”

In 1947, the government accused Zionists of dual allegiance. Zionist organizations were emasculated, while Jewish schools were compelled to replace Hebrew with Bulgarian as the language of instruction, and to remove pictures of Herzl, maps of Israel and the blue collection boxes of the Jewish National Fund.

“These radical measures only inspired intense activity and rebellion in the Jewish community, and served to strengthen its resolve,” writes Haskell. “The desperate economic condition of the Jews following the war, and the government’s refusal to make just restitution, could not but strengthen the resolve of Jews to leave Bulgaria.”

In 1946, a Zionist delegation received an assurance from Dimitrov that Jews were free to emigrate. Two years earlier, David Ben-Gurion, the chairman of the Jewish Agency, had visited Bulgaria to encourage aliyah. In fact, Jews began leaving Bulgaria earlier, with 7,000 arriving in Palestine between 1944 and 1948.

Bulgaria’s attitude to Zionism could be paradoxical. “As the struggle against Zionism within Bulgaria intensified, the government increasingly supported the Haganah and Israel’s War of Independence,” says Haskell.

It is unclear why Bulgaria allowed Jews to depart, but by the late 1940s it was attempting to homogenize its population by encouraging minorities — Greeks, Turks and Armenians — to emigrate. “Thus, the authorities probably saw the establishment of the State of Israel as a way to further reducing ethnic pluralism in a manner which would appear ethical to the outside world, and at the same time absolving itself itself for making full monetary restitution,” he says.

Forty five thousand out of about 50,000 Jews immigrated to Israel. Those who remained behind were ardent communists or people married to Christians.

Conditions in Israel were grim. Housing was in short supply and jobs were scarce. The Israeli government was simply unprepared for the influx. During this difficult period, Bulgarian Jews earned a reputation for hard work, modesty, stoicism and resiliency.

Almost all of them moved to Jaffa, with Bulgarian becoming the language of the streets and shop signs. Restaurants serving Bulgarian food and cafes opened. Clubs catering to the new immigrants sprung up along Shderot Yerushalayim, the main thoroughfare of Bulgarian Jaffa.

Over the next few decades, Jaffa would be, as Haskell writes, “a sentimental center for the Jews of Bulgaria, even as its Bulgarian population dwindled. Jaffa was poor, and as the new immigrants became veterans, they moved up and out. Today, only a small community of mostly retirees and their social clubs remain.”

The Israel-born generation of Bulgarians, he goes on to say, know little, if any, Bulgarian. But there is still a Bulgarian library and a Bulgarian choir in Jaffa.

The Jews who stayed behind in Bulgaria, he says, implicitly rejected their Jewish identity. “All they had left was a notion of solidarity with the Bulgarian people in the struggle against fascism,” says Haskell. “It is easy to understand, then, why at least 90 percent of their children married Bulgarians.”

Upwards of several thousand Bulgarian Jews have immigrated to Israel since the 1990s, their primary impetus having been economic. For all intents and purposes, Israel has become the world center of Bulgarian Jews today. But the Jaffa that Etti and her parents knew so intimately has all but vanished.