Anne Fontaine’s French-language film, inspired by Gustave Flaubert’s 1856 masterpiece, Madame Bovary, and based on Posy Simmonds’ 1999 graphic novel, Gemma Bovery, sizzles with sexual longing and passion.

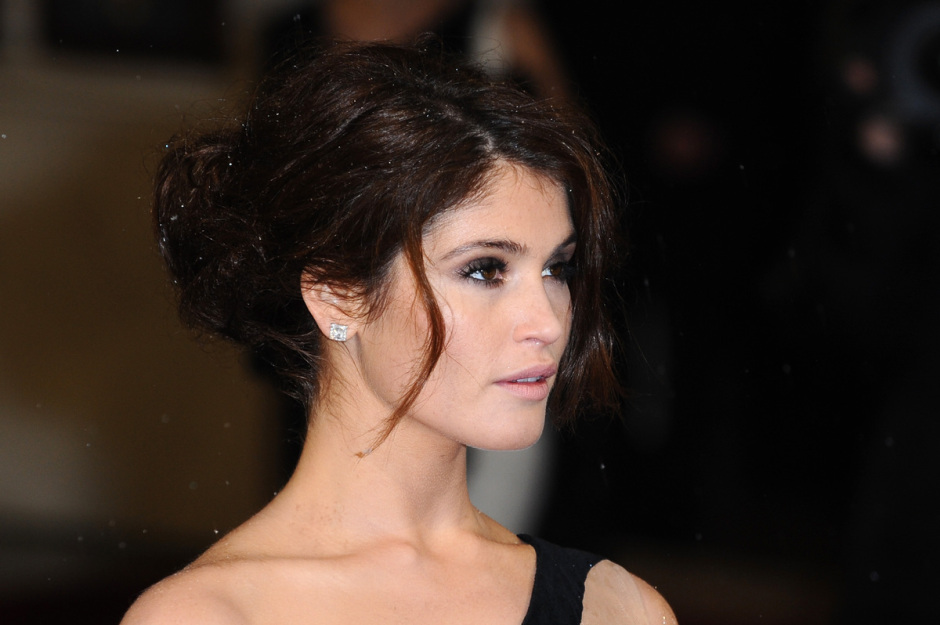

Set in a village in contemporary Normandy, like Madame Bovary, Gemma Bovery unfolds through the recollections of a local baker, Martin Joubert (Fabrice Luchini), who was infatuated with Gemma Bovery (Gemma Arterton), the voluptuous young woman who turned men’s heads.

In one of the first scenes, Joubert reads Bovery’s posthumous diary, an exercise that takes him back in time. The flashback, forms the core of this solidly-crafted, entertaining movie, which opens in Canada on Dec. 5.

Joubert, whose demanding wife barely tolerates him, expresses amazement after learning that the property next door has been purchased by a British couple from London, Charles and Gemma Bovery. Joubert, an admirer of Flaubert’s iconic novel, revels in the notion that his new neighbors carry the same name, even if spelled slightly differently.

From the moment he sets eyes on Bovery’s wife, beautiful and curvaceous, he’s smitten. It’s not clear what his intentions may be, but Joubert is definitely interested, if not obsessed, in Bovery. She, in turn, often frequents his modest bakery to buy his tantalizing assortment of breads and croissants. While Joubert is inexorably drawn to Bovery, she’s in thrall to his expertly baked goods.

As Joubert continually thinks about this lovely creature from across the English Channel, he recites lines from Madame Bovary to himself. Joubert’s flinty wife, however, thinks that Bovery is boring. The reference to Madame Bovary surfaces again when, after showing Bovery how to knead dough, Joubert sings its praises. Much to his disappointment, Bovery, an interior decorator, has not read the novel.

Joubert’s romantic yearning for Bovery is never more than a theoretical construct, but when a bee flies into Bovery’s dress and she frantically asks for his assistance in removing it, he comes to the rescue like a knight on a white horse. It’s about as close to sexual fulfillment as he’ll ever get with the alluring lady.

Bovery, whose quiet husband bores her, has her sights on Herve (Niels Schneider), a wealthy law student whose mother lives in a chateau. Herve, too, is besotted with Bovery, and to no one’s surprise, they become lovers. Joubert, having been spying on them, is annoyed and jealous. As he fumes, they fornicate with gusto, breaking an invaluable porcelain statuette in the process. These sequences, revealing a smidgen of nudity, are risque but hardly explicit.

As in Madame Bovary, Bovery’s extramarital affair dissipates, prompting disappointment and a clearer understanding of what her priories should be. In the meantime, Joubert remains convinced that Bovery’s dalliance will end in death.

Diverging from the denouement of Madame Bovary, Fontaine puts a new and ironic twist on Bovery’s demise. It’s not as dramatic as Bovery’s ultimate fate, but it’s certainly tragic.

Arterton, looking both innocently coy and insinuatingly sexy, blazes a path of red-hot sexuality through the film. Luchini, the second most important character, has his reflective moments. But Arterton is by far and away the most compelling figure in Gemma Bovery.