George H. W. Bush, the 41st president of the United States, was at the centre of the political and military turbulence that lashed and shaped the Middle East a generation ago.

Bush, who died on December 1 at the age of 94, served from 1989 to 1993, during which the U.S. liberated Kuwait in the first Gulf War and played a pivotal role in organizing the short-lived Madrid Conference to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict.

From 1981 to 1989, he was vice-president under President Ronald Reagan. During this period, Iran and Iraq fought an eight-year war, Israel destroyed Iraq’s nuclear reactor and annexed the Golan Heights, and the Israel armed forces invaded Lebanon.

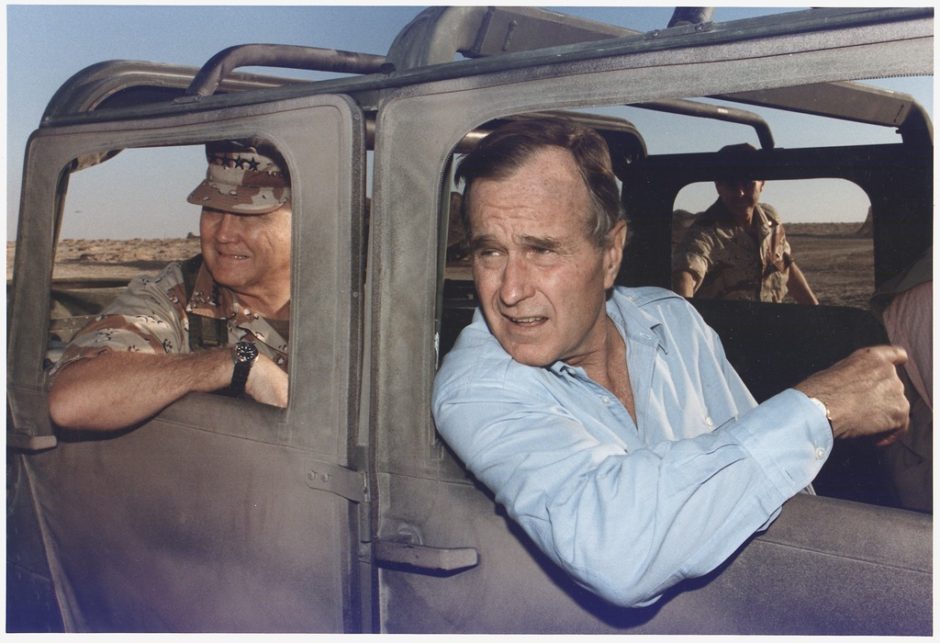

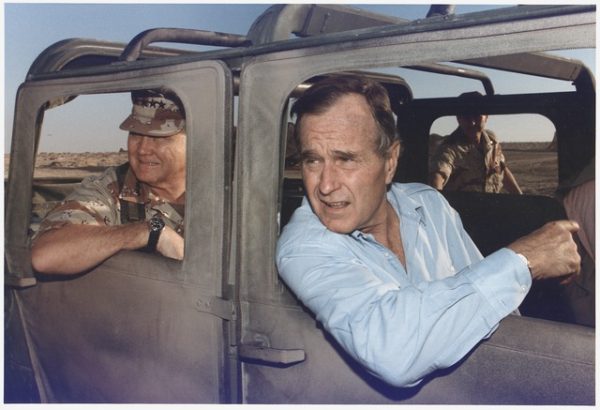

Bush left his greatest impact on the region after Iraqi President Saddam Hussein upended the status quo in the Mideast on August 2, 1990 by ordering the invasion of Kuwait, a U.S. ally. Saddam justified his aggression on the grounds that Kuwait was Iraq’s 19th province and that Kuwait had stolen Iraqi oil by means of slant drilling. Iraq, still licking its wounds from the war with Iran, sent 300,000 troops into Kuwait, which sat on 20 percent of the world’s petroleum reserves.

The United Nations unanimously condemned the Iraqi occupation and imposed a trade embargo on Iraq. Fearful that Iraq would remain indefinitely in Kuwait and invade Saudi Arabia — the United States’ key ally in the Arab world — Bush and his secretary of State, James Baker, cobbled together an international coalition of more than 30 nations to confront the Iraqis.

In Operation Desert Shield, the United States dispatched several hundred thousand troops to Saudi Arabia, where the last of them would remain until 2003. The presence of American soldiers in the oil-rich desert kingdom angered many Saudis, including Osama bin Laden, who would become the leader of Al Qaeda. Later, he would cite this as a reason for the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks against the United States.

On January 16, 1991, in Operation Desert Storm, the United States and its allies launched a concerted air campaign to degrade Iraqi forces in Iraq and Kuwait. Iraq responded by firing Scud missiles at Israel and Saudi Arabia. Thirty nine Scuds slammed into Israel, mainly hitting Tel Aviv and causing considerable property damage and some fatalities. Israelis donned gas masks in bomb shelters. Still other Israelis left the coastal plain in droves.

Fearing that an Israeli military reaction would imperil the coalition ranged against Iraq, Bush strongly urged Israel to exercise restraint and refrain from responding to Iraq’s bombardments. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir was sorely tempted to retaliate, but abided by Bush’s request after he ordered the deployment to Israel of two Patriot missile defence batteries and 700 American troops to operate them. By all accounts, the Patriots were mainly ineffective.

To further appease Israel, Bush established a direct communication link between the U.S. defence secretary and the Israeli defence minister.

On February 24, the United States and its allies invaded Iraq and liberated Kuwait in an operation that lasted about 100 hours and cost the lives of 148 U.S. soldiers and thousands of Iraqi troops.

Bush had no intention of occupying Iraq or unseating Saddam. As he put it, “To occupy Iraq would shatter our coalition, turning the whole Arab world against us, and make a broken tyrant into a latter-day Arab hero. It would have taken us way beyond the imprimatur of international law … assigning young soldiers to a fruitless hunt for a securely entrenched dictator and condemning them to fight in what would be an unwinnable urban guerrilla war.”

Bush encouraged Iraq’s Shi’a majority to stage a revolt against Saddam, a Sunni Muslim. When they rebelled, Bush abandoned them to their fate, allowing Saddam to punish the rebels. Bush, however, defended the Kurds of Iraq. In 1992, he established a no-fly zone in northern Iraq to protect the Kurds. It enabled the Kurds to create a semi-autonomous region and emboldened them to call for independence from Iraq.

Later, the no-fly zone was extended to southern Iraq to protect the Shi’a population there.

In the wake of the first Gulf War, Bush compensated Israel for its losses to the tune of $650 million, promised to maintain the flow of $3 billion worth of annual military aid to Israel, and upgraded the United States’ relationship with Israel by holding joint exercises and training, pre-stocking weapons and munitions in Israel, and enhancing joint research and development projects.

And in a sop to his Arab allies, Bush pledged to work toward a resolution of the intractable Arab-Israeli dispute.

Bush persuaded Israel and the Arab states to send delegates to the Madrid peace conference, which took place from October 30 to November 1 and marked the first time Israeli and Arab leaders sat in the same room. Long on symbolism but short on substance, it was little more than a grand photo opportunity, but it led to further talks between Israel and the Palestinians and the Oslo peace process in 1993.

Before the Madrid conference got under way, tensions flared between the United States and Israel.

Baker, Bush’s point man in the Middle East, started visiting the region regularly in an attempt to kick start talks between Israel and the Palestinians. The United States had been cultivating the PLO, Israel’s arch enemy, for the past two years to gauge whether the PLO could represent the Palestinians in future negotiations with Israel. But after the PLO failed to condemn an abortive Palestinian terrorist attack against Israel in May of 1990, the United States broke off discussions with the PLO and decided that the Palestinians could be represented by a non-PLO delegation at peace talks.

Shamir, in the meanwhile, laid down his government’s hard-line conditions for peace negotiations. To Baker, they seemed unreasonable. In a gesture of annoyance and frustration, he left his White House phone number: “I have to tell you that everybody over there should know that the telephone number is 1-202-456-1414. When you’re serious about peace, call us.”

Israel’s network of settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip was one of the issues that divided the United States and Israel. Bush and Baker believed they were an obstacle on the path toward peace. Shamir, a hawk, was a strong proponent of the settlement project and rejected the notion that Israel had to withdraw from the occupied territories as a concession to the Palestinians.

This contentious issue came to a head in mid-September of 1991, when Bush announced he would temporarily withhold $10 billion in U.S. loan guarantees to Israel unless it stopped building settlements. “A 120-day delay is not too much for an American president to ask for with so much in the balance,” he said. “We must give peace a chance. We must give peace every chance.”

“It is in the best interest of the peace process and of peace itself that consideration of this aid for Israel be deferred for simply 120 days,” Bush added. “I think the American people will strongly support me in this. I’m going to fight for it because I think this is what the American people want, and I’m going to do absolutely everything I can to back those members of the United States Congress who are forward-looking in their desire to see peace.”

And in a memorable comment, Bush likened himself to David in combat with Goliath, complaining “there are 1,000 lobbyists up on the Hill today lobbying Congress for loan guarantees for Israel and I’m one lonely little guy down here asking Congress” to delay the issue.

The tension between the Bush administration and Israel was now palpable. According to former New York City mayor Ed Koch, Baker could no longer tolerate Shamir’s intransigence or the support he received from pro-Israel Jewish lobbyists in Washington. “Fuck the Jews, they don’t vote for us anyway,” he reportedly said.

Baker denied uttering this expletive.

Eventually, the Bush administration granted Israel the $10 billion in loan guarantees, but this did not happen until Yitzhak Rabin defeated Shamir in the 1992 general election and replaced him as prime minister.

Bush was also of assistance in bringing Ethiopian Jews to Israel. In 1985, when he was vice- president, he persuaded Sudan to allow U.S. transport planes to fly 900 Ethiopian Jews to Israel after they were stranded during Operation Moses. Six years later, when he was president, he convinced Ethiopia to allow 14,300 Jews to leave the country in Operation Solomon.

Bush, while being generally pro-Israel, opposed Israel’s settlement-building policy in the occupied areas. Every president before and since Bush has argued that the settlements are counter-productive in the search for peace. But apart from this major disagreement, there was little daylight between the United States and Israel during the Bush era.